Istanbul Design Biennial sets out to challenge limits

Barçın Yinanç

“What would you like for the main course, steak, salmon or grilled grasshopper?” the waiter asked me. I had never eaten grasshopper before, but I couldn’t decide. “I need some time to decide. Can you go around the table to take the others’ orders and come back?” I said. The waiter told me I was the only one who hadn’t ordered.

“What would you like for the main course, steak, salmon or grilled grasshopper?” the waiter asked me. I had never eaten grasshopper before, but I couldn’t decide. “I need some time to decide. Can you go around the table to take the others’ orders and come back?” I said. The waiter told me I was the only one who hadn’t ordered.There was no time to think, and my initial instinct to always try something new made me say “grasshopper.” Just as the waiter was turning around to go back to the kitchen, I just visualized the creature and told him, “Wait, I’ve changed my mind.” While he was taking note; I changed my mind once more.

I said to myself: “Why not? When I went to Japan I tried all the food I hadn’t tried before. I am not a vegan. I eat all sort of other animals. I could have lived in a country where they eat them. I could end up alone on an island where there is nothing but grasshoppers to eat. Why shouldn’t I try them?”

This is exactly what the second Istanbul design biennial wants you to do: ask, debate and challenge your limits.

“People expect to see some different design objects when they think of a design biennial,” Bülent Eczacıbaşı, the chair of the Board of Directors of the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (İKSV), told a group of journalists last week at a lunch which included grasshoppers on the menu, adding that the biennial was not about weird designs.

“Biennials exhibit the most extreme developments. They want to open debate and be debated. Some complain they don’t understand. Those who cannot understand and those who cannot be understood are both right. But this is in the nature of biennials,” said Eczacıbaşı.

It is precisely this nature of biennials that motivated the İKSV to organize a design biennial when they started contemplating how the İKSV could contribute to a platform that could contribute to the shaping of design policies.

“We chose the most difficult one by opting to organize a biennial. It takes two years to prepare them and also requires an important intellectual effort to follow them,” said Eczacıbaşı.

The success and the interest generated by the first Istanbul design biennial exceeded the expectations, according to Eczacıbaşı, and this seems to have pushed the İKSV to aim higher. “The Istanbul design biennial needs to take its place on the global design map. Our aim is to introduce it to the calendar of those who are shaping the design world,” he said.

Projects from 200 designers

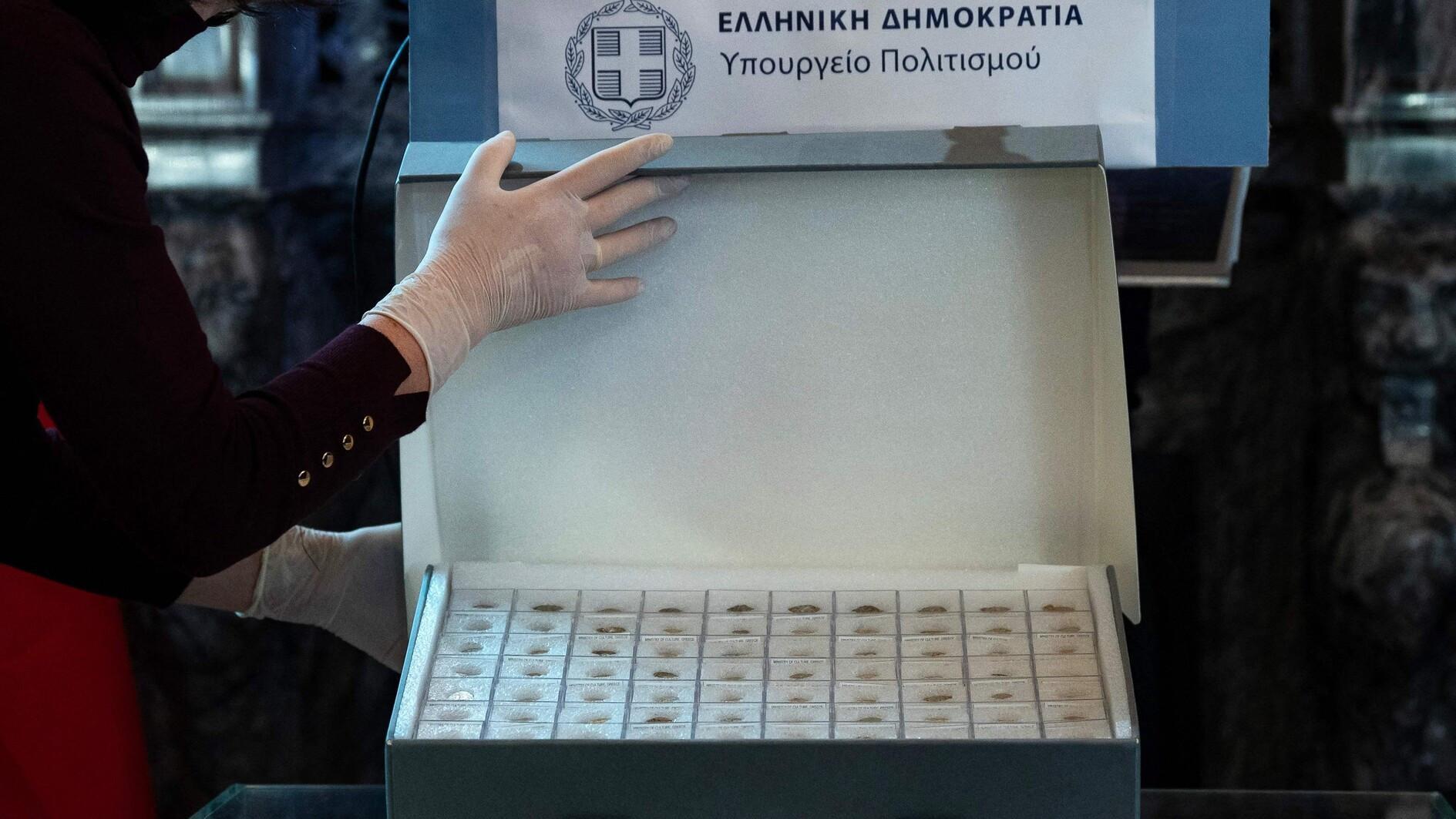

Inspired by French poet Paul Valery, the second biennial, whose motto is “the future is not what it used to be,” will exhibit 53 projects from 200 designers from two dozen countries.

While the projects are about the future; it will certainly tell us a lot about our present. The present-day global preoccupation about food shortages seem to have affected some of the designers for the future, such as the Mansour Ourasanah project LEPSIS: The Art of Growing Grasshoppers. Operating from the need to alleviate hunger in the face of the world’s growing population, the U.S.-based designer, who grew up in West Africa, has come up with a very different kitchen appliance. Lepsis is designed to provide a food source high in protein yet bred in a more energy-efficient way.

Open between Nov. 1 and Dec. 14, the main venue of the design biennial will be the Galata Greek Primary School. As the biennial is free of charge, organizers believe this will facilitate accessibility. Deniz Ova, the director of the biennial, expects the number of visitors to double the number of the first biennial, which was visited by 45,000 people.

Zoë Ryan is the curator of the second Istanbul Design Biennial, which will include several activities like panel discussions and film screenings. Some 66 percent of the biennial’s budget comes from sponsors, which include Arçelik, Doğuş Grubu, Bilgili Holding, ENKA Vakfı and VitrA. Eighteen percent of the budget has been provided by state institutions, like the Prime Ministry’s Promotion Fund.

Some of the designs might not be too far away. “Just as we’re talking, whatever we say may have already become history,” Ova said.

Perhaps the grasshopper breeder Lepsis could become an inseparable appliance in our kitchen, just like an oven.

Five people among a dozen journalists or so ordered grasshoppers during the lunch – a not insignificant number for a country which is rather traditionalist in its culinary tastes.

Ultimately, though, I didn’t end up eating grasshopper, but something else; it was just a trick on the part of the İKSV staff, who are always innovative when it comes to attracting attention.