Women’s magazines that redefined feminism in Turkey

EMRAH GÜLER

The emergence of women’s magazines, run by women, with women and from a woman’s perspective, goes back to the late 1970s and early 1980s.

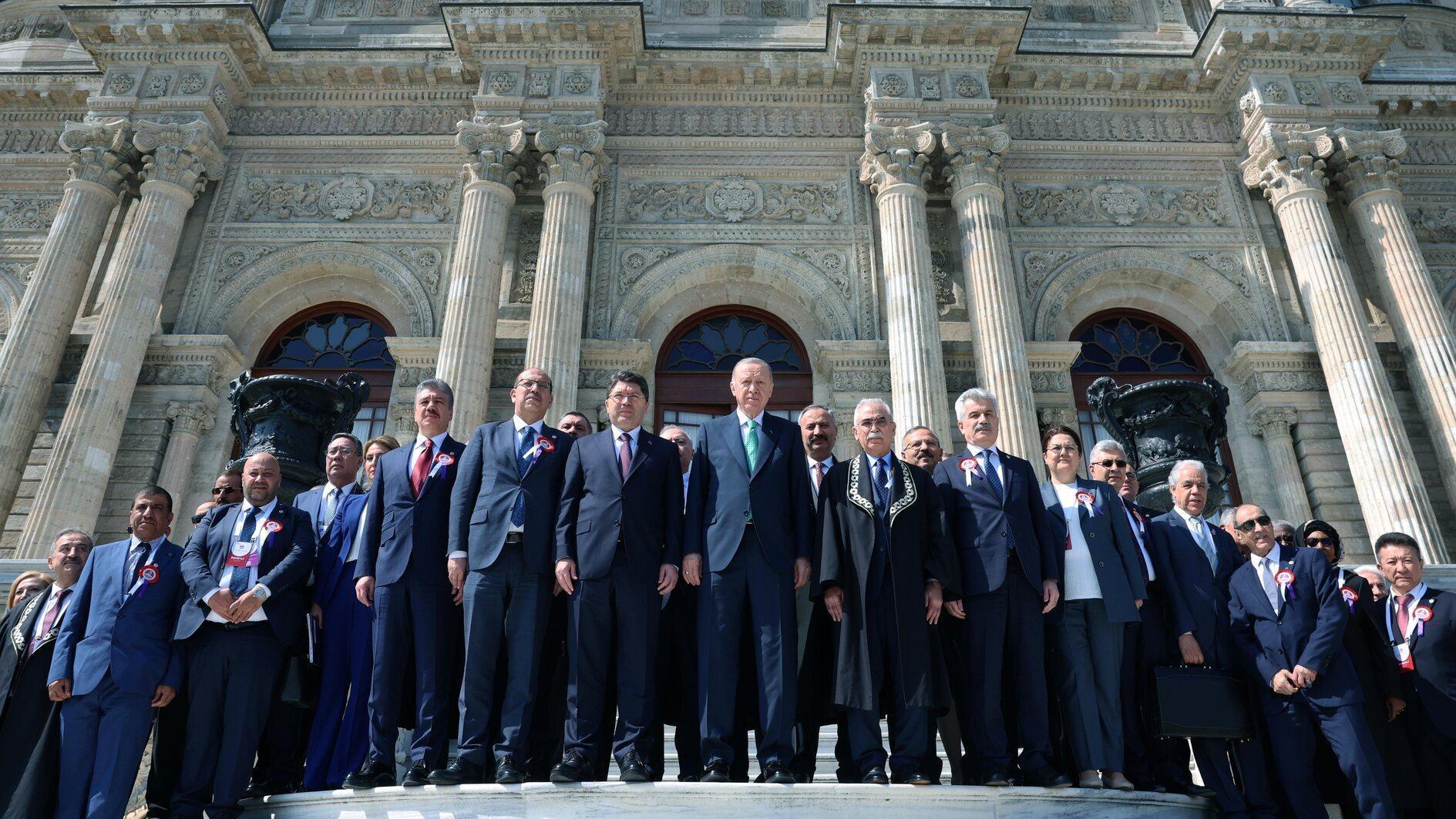

In 1886 today, a group of women collectively voiced their concerns against a male-dominated society through a magazine very few people know of. Şükufezar, meaning flower garden in Persian, was run by an editorial and writing team consisting only of women who refused to be acknowledged through their husbands’ names. A century later, other magazines would take the women’s issue and the feminist movements to a broader public. Here’s a look at some of the women’s magazines in Turkey that took women’s liberation to a whole new level.One good that might have come out of the 1980 coup in Turkey and the subsequent military regime was the establishment of an autonomous contemporary feminist movement that was already emerging, and a public women’s struggle that would lead to a prolific feminist academia, activism, and media today.

In an environment that was brutally depoliticized in the early 1980s, a group of women taking women’s issues into the public arena felt as no threat to the status quo. The blossoming of a feminist movement among a handful of urban, educated, middle-class women coincided with Turkey’s liberalization policies, the definitions of public and private being rewritten, and the repressed media opting to find untouched markets.

The emergence of women’s magazines, run by women, with women and from a woman’s perspective, goes back to the late 1970s and early 1980s, and can be traced back to a single name, Duygu Asena.

Writer, journalist, editor-in-chief, activist, pedagogue, and copywriter, but one label that was perhaps associated most with late Asena’s name was feminist. A testament to the cultural influence she exerted on the position of women in Turkey, and how she turned the women’s movement into a major part of everyday politics.

More magazines follow

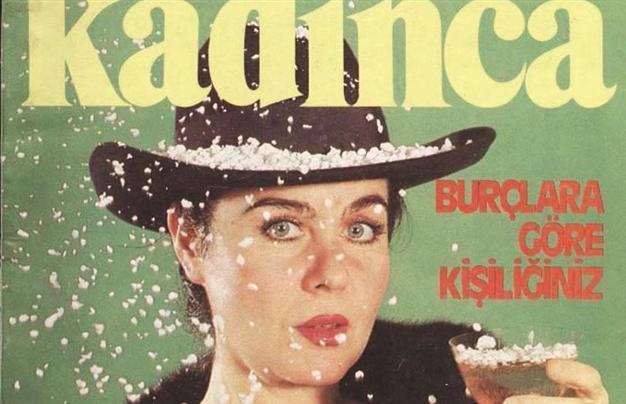

As the editor-in-chief, Duygu Asena launched Kadınca in 1978, which soon became a significant source of the feminist movement and continued to be so throughout the 1980s. The penetration into this uncharted market was soon followed by other women’s magazines like Kadın, Elele, and Vizon. “These magazines offered their readers information about ‘new’ female goals, such as employment, education, health, female sexual pleasure and equal rights, alongside fashion, home and childcare,” Süheyla Kırca from Istanbul’s Bahçeşehir University wrote in an academic article.

Kırca wrote, “Representations of women in the magazines, as well as the actual roles of Turkish women in society, began to move away from the traditional conception.” Kadınca featured stories on violence against women, explored sexuality from a woman’s perspective, and addressed marriage problems openly. Asena bravely advised women to get out of unhappy marriages. In one interview she said of the first years of Kadınca; “It was the first criticism of marriage.”

From Monday meetings to Monday magazine

From Monday meetings to Monday magazineWhat Duygu Asena had managed with vision, mastery and devotion was to take the women’s movement from its shell and move it toward middle-class consciousness. For Asena, Kadınca called “on women to be daring and aggressively energetic, exhorting them to discover themselves, especially their feelings, capabilities and sexuality.” In 1992, she launched another magazine, Kim, that once again took the feminist motto “personal is political” to its heart. In an interview in the 1990s, Asena had said, “We’ve come a long way, but there’s still a long way to go.”

The 1990s was a period when the collective spirit of the feminist movement became more fragmented, different groups becoming more closed-up and focusing on different issues. The next big feminist magazine was launched in 1995, to address this fragmentation and hopefully become a collective voice. Starting with a print version and ending with a web format in 2007, Pazartesi ran as more of a political magazine than a popular one, the multiple voices dwindling toward its final years.

The name of the magazine, meaning Monday, was inspired by the weekly meetings on Mondays that started out with more than 100 women, eventually going down to the 20-something core team in the course of two years before the magazine’s launch.

The core team, including names like Ayşe Düzkan, Gülnür Acar Savran and Filiz Koçali, were activists who had previously worked in feminist campaigns like the Purple Needle campaign against sexual harassment, campaigns against domestic violence, activities against the abolishment of Law 159 (requiring women to take permission from their husbands to be able to work) or Law 438 (reducing the punishment for rapists if the victim was a prostitute), among others.

Writing about such diverse issues as reproductive health and sexual pleasure to Civil Law and incest, Pazartesi was the picture of nearly all of the feminist issues and perspectives throughout late 1990s and early 2000s.

As Eda Aslı Şeran wrote in an article on the magazine, “Pazartesi has left behind a 12-year legacy of history and feminist resources that is waiting to become the subjects of theses and books. The articles and news in Pazartesi are no doubt the greatest resource for any researcher looking to analyze the development of the feminist movement in Turkey.”