What does Russian salad have to do with press freedom in Turkey

Written by Altan Öymen Translated by Alkım Kutlu

Year 1945… December 3, a Monday… The headline of Tanin newspaper, printed in Istanbul, goes; “Rise, oh people who value the nation” (“Kalkın Ey Ehl-i Vatan”). This was an out-of-context quotation from the Ottoman Turkish journalist and political activist Namık Kemal. It was originally used to motivate the people to take action during the hard times the country was going through in the 19th century. The pro-government Tanin newspaper, on the other hand, was calling the people to “rise up and do what is necessary” against a dissident competitor.

The editorial was written by the owner and editor-in-chief of the newspaper, Hüseyin Cahit Yalçın. It was like an order of attack. The outcome was as such.

At the time, Yalçın was also a member of parliament from the Republican People’s Party (CHP) during the single party regime. He had also been a member of parliament during the rule of the Union and Progress Party (UPP) in the Ottoman era. He survived an attempted murder by coincidence during “the March 31 incident,” an attempted countercoup in 1909.

During the Republican period, Yalçın was suspended from journalism for a while because of his writings criticizing the single-party regime. But during İsmet İnönü’s presidency, he returned to journalism and the political arena. His writing on December 3, 1945 was like a sign of an approaching storm during the rocky period of Turkey’s “transition to democracy.”

According to Yalçın, Turkey was under “a threat of communism” after World War II. The source of this communism was the Soviet Union. However, Moscow had propagandists in Turkey as well and a “national front” had to be built to fight them off, Yalçın argued.

The Sertels

The Sertels

Sabiha and Zekeriya Sertel

Among the people Yalçın claimed to be the Soviet propagandists were Tan newspaper writers. They were led by “the Sertels.” One of them was the owner and editor-in-chief, Zekeriya Sertel. He was born in the Ottoman province of Thessaloniki in 1890. His father was well off. After finishing “idadi” (high school) in Thessaloniki, he moved on to Istanbul where he started in journalism. After a while, he went to France, then America, for his graduate education where he received a journalism degree.

Zekeriya Sertel remained in Ankara for a while upon his return to Turkey. He became one of the first heads of Turkey’s Press and Publication General Directorate. Then he returned to Istanbul, to journalism.

Anti-German publications

His spouse Sabiha Sertel, whom he married during his education, also chose journalism as her profession. Together they published one of the first popular pictorials in Turkey. “Resimli Ay” was a magazine that dedicated a large section to art and literature. A big part of Nâzım Hikmet’s famous poems were first published in that magazine. Hayat Encyclopaedia, the only encyclopedia of Turkey for many years, was also among the publications of the Sertels.

The Sertels then entered the Tan newspaper period by getting into a partnership with famous publisher Halil Lütfi Dördüncü. Zekeriya Sertel wrote the editorials of the newspaper. Sabiha Sertel was a front page writer. There were many famous writers in the newspaper, including Aziz Nesin.

During World War II, the Sertels supported the Allies against the Germany-Italy partnership. After Germany’s attack on Russia, they intensified their anti-Germany publications.

Support for the Democrat Party

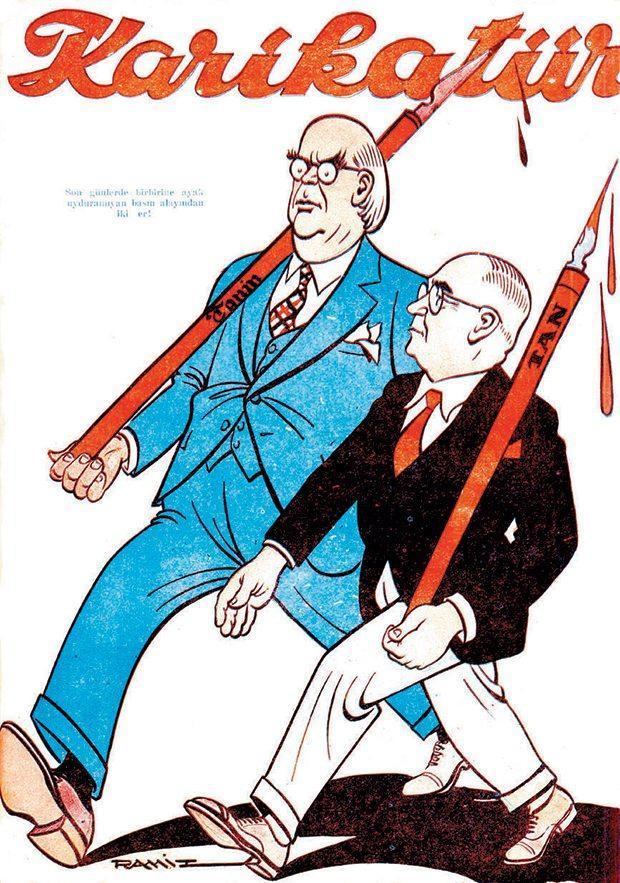

Support for the Democrat PartyZekeriya Sertel and Hüseyin Yalçın once had a very good relationship. Ramiz’s caricature is a reminder of those times.

The Sertels were also pleased at Turkey’s success at remaining non-combatant during the times when all neighboring countries were drifted into the hell of war. For them too, Turkey’s initiation of its “transition to democracy” after the end of war in May 1945 was the start of a new process. They themselves wanted to be active in that process. They supported the founding of new parties against the governing CHP, especially the Democrat Party (DP).

They decided to publish a political magazine alongside the newspaper just to contribute to that process. The name of the magazine was Görüşler. Its first issue came out on Dec. 1, 1945. The magazine, quite clearly from its first issue, supported the Democrat Party.

‘Freedom in Chains’In fact, at first, they wanted to publish the writings of the founders and spokespeople of the Democrat Party such as Celal Bayar, Adnan Menderes and Fuat Köprülü. Zekeriya Sertel had made propositions to some of them regarding this matter and had gotten positive responses. He declared in the first issue, “In our next issue, we will publish Menderes and Köprülü’s writings and a statement by Celal Bayar.”

The actual arbiter of Görüşler was Sabiha Sertel. This was evident from the piece she wrote for the first issue. This piece was one of the targets of Yalçın’s article entitled “Rise, oh people who value the nation” where he voiced his reaction towards the Sertels. Pro-CHP Yalçın wrote the following as a response to pro-DP Sabiha Sertel’s piece “Zincirli Hürriyet” (“Freedom in Chains”):

“Namık Kemal’s voice is today’s motto. Rise up, oh people who value their nation. The fight begins and so should we. Because we cannot let the most ferocious and merciless propaganda pour scorching, despairing, unnerving propaganda venom into the souls of Turkish citizens. Every Turk who wishes to have a nation and live free and autonomously in this nation is obligated to withstand this propaganda.”

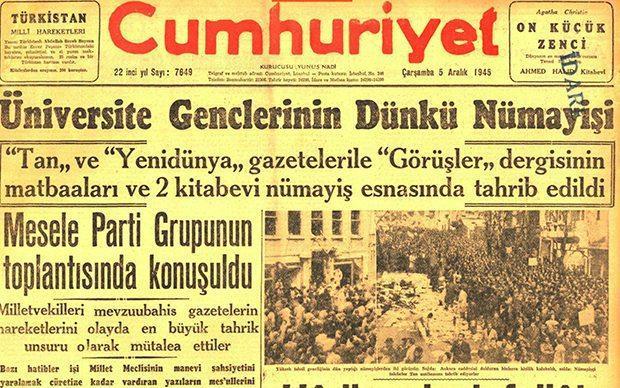

Mob attack launchedThe “order of attack” was executed on Dec. 4, 1945. It made the headlines on Dec. 5.

In the writing Yalçın speaks of, Sabiha Sertel criticized the CHP government for their conduct during the single party era. Yalçın selected certain phrases and came to a conclusion that they were praising communism. He commended the single party government of the period for “tolerating” those writings:

“There cannot be a more free press in another country. Let her call out from the fifth column that there is no press in the country. Let her call out that there is no freedom of opinion. Silence and toleration is the best and muffling response towards their publications that are far from solemnity, obstreperous and aggressive, produced only to provoke the people and the government.”

“Free citizens”After commending the government for their “tolerance towards critique,” Yalçın emphasized it was upon the citizens to take action, not the government and wrote this striking sentence: “It is not on the government to respond on this matter. The say is in the hands of journalists and free citizens.”

This, of course, was a clear call of duty to “journalists” and “free citizens.”

Yes, the say is now in the hands of “free citizens” alongside journalists… However, how will these citizens put that “say” into action? Let us hear that from two people on the two opposing sides that came face to face on Dec. 4, 1945: One of them, the owner of Tan newspaper, Zekeriya Sertel and the other, Organ Birgit, a journalist and politician, who was among the demonstrators at the time.

Governor reassures journalist: Do not worry, there is no danger

In his memoirs, Zekeriya Sertel writes about the developments of Dec. 3:

“Someone familiar came and told us university students were going to rally in front of the printing press. He counselled us to take some precautions in case there was some excess behavior. So it seems that the government wanted to do what he could not through the law, by provoking the youth. I immediately made a phone call to the Governor Lütfi Kırdar. I told him of this news and requested him for governmental precautions. The governor said: ‘I know and I took the necessary precautions, do not worry.’ I had not cared that much about the incident, thinking it was going to be one of the rallies that usually occur.”

Zekeriya Sertel’s notes on the next day are as the following:

“Early on that morning one of the university students phoned my house and warned me that some of the youth were preparing to raid the ‘Tan Printing Press’ and to not go down to the press. I made another call to the governor letting him know and asked him what measures he took. He said: ‘Do not worry. I surrounded the printing press with police forces. There is no danger.”

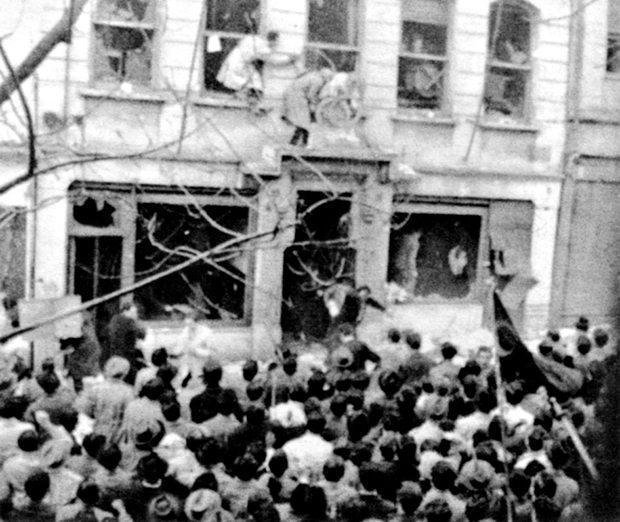

Police do not perform duties“On Dec. 4, 1945, a fascist university group attacked the printing press with premade axes, sledge hammers and red ink bottles in their hands. The police at the scene remained oblivious and did not attempt to perform their duties. The demonstrators broke down the door with axes and went inside. They broke machines with sledge hammers, broke windows and vandalized everything inside. They ravaged anything they got their hands on. Then, with the red ink bottles in their hands, they cried out ‘Where are the Sertels?’ while searching for us.

“All of this was happening right in front of the eyes of the police. When the demonstrators failed to find us, they set out with wild cries. They headed over to Istanbul’s Beyoğlu neighborhood where they went to the printing press of ‘La Turquie,’ published by writers Sabahattin Ali and Cami Bayburt. After vandalizing it as well, they attempted to cross over to Kadıköy and invade our home.”

Feeling besiegedZekeriya Sertel was at home during the incidents. He followed up on them from the information he gathered from friends he reached through the phone. He summarizes the last conversation he had with the governor:

“We were watching the incidents from our home. I called the governor upon receiving the latest news: I said: ‘Are you pleased with the outcome of your precautions. Now the fascists are coming to my home. You let them tear down my printing press, at least prevent the attempt on our lives.’

“The governor did not even see a necessity to apologize. He only gave yet another assurance: ‘Do not worry. What is done is done. But your lives are under safety. I ordered the ferry the youth is on to go straight to the Princes’ Islands without stopping by Kadıköy. There is no danger to you.’ Then he added: ‘But where are you now? If you are home, go elsewhere as a precaution. Do not sit at home.’”

Suspects released, victims on trial

Zekeriya Sertel and his spouse Sabiha Sertel took the governor’s advice and spent that night and several others in the houses of their friends.

Meanwhile, they received the news: The police investigations regarding the suspects of the attack at Tan were continuing. During the incidents, 7 or 8 suspects had been caught. But then they were all released.

However, four people were called in for an interrogation with motions to trial. All four were the owners and those responsible for the now ravaged Tan newspaper: Zekeriya Sertel, Sabiha Sertel, Cami Baykurt, Halil Lütfi Dördüncü... The victims had now become the suspects.

They faced three years in prison with charges on evoking hate among the people and provoking the crowds. They were arrested on these grounds and served three months in prison. Their trial was conducted and they were sentenced to three years of penal servitude as the prosecutor demanded.

Verdict overturned

However, the verdict was turned away by the Supreme Court and they were discharged. They “got away with” three months of confinement rather than three years. After that, they had to spend the rest of their lives abroad.

In his book “Hatıralarım” (“My Memoirs”), which he wrote at an old age, Zekeriya Sertel writes about how the years following his family’s leaving of the country have not been easy. He writes:

“How was my life these 25 years? It is a long novel. We have seen good and happy days as well as dark and unhappy ones. But the yearning for our homeland did not leave us for even an instance. Even those that leave their countries for a short time feel homesickness after a little while and wish to return to their homes as soon as possible. (…) We were sort of living a life of exile, and we still are. Not being able to return to your motherland is not a tolerable pain; it is a horrible thing that makes the longing insufferable. Only Nâzım Hikmet and I would know what this means. His poems on longing are the expressions of my days of longing. I often weep reading his poems. Anyway, let us move on…”

Looking from the other side

Now let us look at the incidents from the perspective of Orhan Birgit, who was on the other side of the issue. Birgit, then, was a freshman at the Law Faculty of Istanbul University. He tells of how he found out about the incident and how the students arrived in front of the printing press:

“On the morning of Dec. 4, we were auditing the Constitutional Law class of our professor Hüseyin Naili Kubalı. The door was suddenly opened. A fair-haired student, understood to be from upper divisions, and made a move towards the stand.

“The professor and we were watching what was about to happen in a reserved manner. This person, who we learned to be Tahsin Atakan, said something to Kubalı then got on the stand and presented the Tanin newspaper.

“Hüseyin Cahit Yalçın’s writing covered the front page as a headliner. I remember the eight column headline to this day: Atakan, who incorporated the ‘Rise, oh people who value the nation’ writing into his speech, was saying that communist propaganda was being made in the Sertels’ Tan newspaper and inviting us to gather in the Beyazıt Area.”

Famous writer Kısakürek salutes crowdBirgit explains that him and his friends obeyed the call and went towards the Cağaloğlu neighborhood from Beyazıt.

“The crowd was headed to the Tan newspaper. I was neither in the front nor back. I sort of let myself flow with the crowd. This was my first rally. I felt no remorse. I was the sort of person who did not take into account the outcome of a certain situation. We passed the Governorate Building. On the left side of the street, stood famous writer Necip Fazıl Kısakürek at the window sill of the building that housed daily Vakit Yurdu, published by the Hakkı Tarık-Asım-Rasim Us brothers. Those in the convoy made a display of affection towards Kısakürek who saluted them with enthusiasm. The crowd sped up and arrived in front of the Tan newspaper.”

Then, what happened first in front of the Tan Publishing Press and later on in the march on the iconic Taksim Square. With Birgit’s narration:

Salads renamed “Those that provoked the participants of the rally first broke down the windows of the Tan building then shortly after, went inside. They made their way to the roof and on the way destroyed anything they came across; paper coils were removed and dragged all the way to the car ferry in the Sirkeci neighborhood, the rotary presses were smashed.

“This rally, whose main participants I later became friends with, was the first big rally I had ever seen. Those friends all said whole-heartedly that none of them had thought such a development would follow during its arrangement.

“The crowd did not stop destroying at the Tan Printing Press but went towards Taksim. The Russian salads sold in the delis on Istiklal Avenue were presented and labelled American salad. The whole incident had turned into an anti-communist action. The La Turquie magazine and the printing press that published it in the Tunnel neighborhood were both vandalized as well.”

What happened to the perpetrators?So, the summary of the incidents that commenced in front of the Tan newspaper on Dec. 4, 1945 is as such. There is not much more to write on it. Let us finish this piece with pointing to this: What happened to those that organized and inspired the attack on the Tan newspaper, which caused actual damage to both Tan and other publications’ employees, work spaces, machines and equipment?

Surely, there were many of them in the crowd. It is not possible for all of them to know the situation. There is no one who has been investigated and prosecuted as those responsible for the incident. However, it is evident that some of the people feel remorse because of their behavior at that time.

The late Yalçın, in his advanced age, was the lead writer of the newspapers I worked in when I first started the profession (Ulus, Yeni Ulus, Halkçı). He would be very displeased at any sort of mention of the Tan incidents of 1945. Obviously, we young writers had no means to bring up the subject to him. However, we all had a similar impression and faith: Yalçın must have, on more than several occasions, said, “I wish I had never wrote” that “Rise, oh people who value the nation” piece on Dec. 3,1945.

Learning from historyBesides, even if our guesses are wrong, he was reminded of this history though incidents: During the Democrat Party government between 1950 and 1960, Yalçın was one of the writers who had the most amount of lawsuits filed against him. Some of those cases resulted in the shutting down of the newspaper he wrote in. In some, the punishments were not just inflicted on his newspaper but also on himself. In fact, he faced the obligation of spending his 80th birthday in prison.

Of course, just as the government’s treatment towards the Sertels, the treatment seen fit for Yalçın was exceptionally wrong. It did not fit democracy, law or logic… Also, it did not avail the government that saw these treatments as fit for them.

These actions did not avail the previous periods and will continue to not do so now.

There is an uncountable amount of benefit for the interested parties to come to this realization.

Year 1945… December 3, a Monday… The headline of Tanin newspaper, printed in Istanbul, goes; “Rise, oh people who value the nation” (“Kalkın Ey Ehl-i Vatan”). This was an out-of-context quotation from the Ottoman Turkish journalist and political activist Namık Kemal. It was originally used to motivate the people to take action during the hard times the country was going through in the 19th century. The pro-government Tanin newspaper, on the other hand, was calling the people to “rise up and do what is necessary” against a dissident competitor.

Year 1945… December 3, a Monday… The headline of Tanin newspaper, printed in Istanbul, goes; “Rise, oh people who value the nation” (“Kalkın Ey Ehl-i Vatan”). This was an out-of-context quotation from the Ottoman Turkish journalist and political activist Namık Kemal. It was originally used to motivate the people to take action during the hard times the country was going through in the 19th century. The pro-government Tanin newspaper, on the other hand, was calling the people to “rise up and do what is necessary” against a dissident competitor.

The Sertels

The Sertels Support for the Democrat Party

Support for the Democrat Party