Ukrainian convicts take up arms in bid for redemption

KIEV

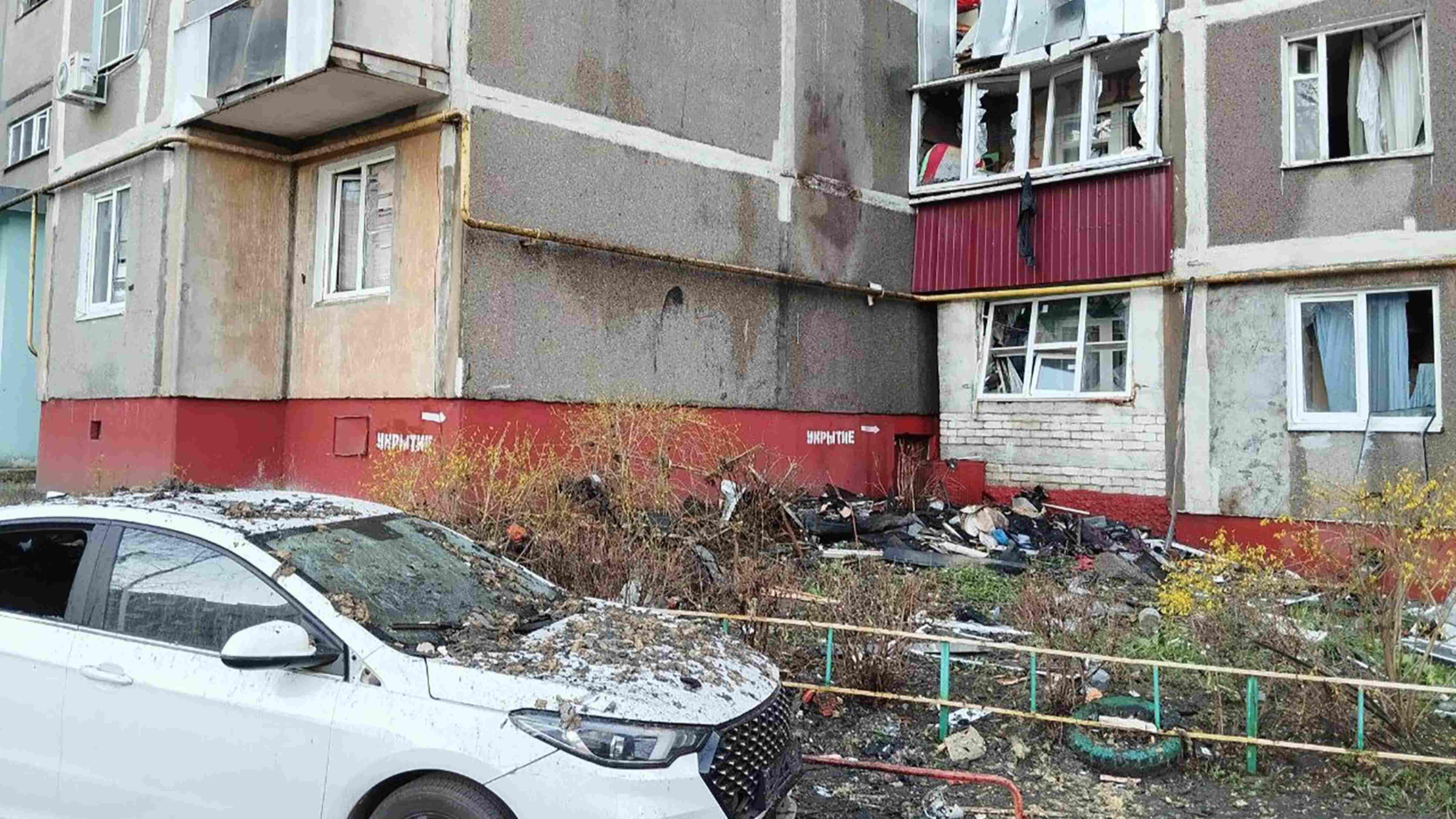

Ukrainian convicts Volodymyr Barandich (C) and Arthur Kachurovsky (L) and a guard (R) wait in a courtyard of the Boryspil penal colony outside the town of Boryspil, Kiev region, on July 4, 2024, amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Artur Kachurovsky is one of thousands of Ukrainian prisoners who have taken up the offer to join the army and fight the Russians in return for a pardon.

The 27-year-old, who was jailed for theft, is being released on parole to join the army and would only be able to return home once the war ends.

"Maybe life over there will fix me, just a little bit, for the better," he told AFP in Boryspil prison near Kiev as he waited to be deployed.

With Russia's invasion dragging on into its third year, Ukraine is seeking to boost its critically stretched manpower, including with tougher draft rules and a law allowing inmates to fight.

Since the bill was passed in May, the justice ministry says more than 5,000 imprisoned men from across the country have applied to join up.

The law only excludes people convicted of the most serious crimes, including sexual violence, killing two or more people and serious corruption.

'Prisoners took Bakhmut'

Earlier in the war, Ukrainian officials had mocked Russia for recruiting inmates into the ranks of the infamous Wagner mercenary group.

The practice drew comparisons with the drafting of gulag prisoners by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, who ordered criminals to atone for their sins in blood.

Ukrainian officials may recoil at parallels with Wagner.

But the analogy is popular among some inmates.

"Prisoners took Bakhmut. Unfortunately, not guys from our side," Kachurovsky said with a smile.

He was referring to the capture of the eastern city by Wagner forces largely composed of former convicts.

At least 40,000 prisoners joined Wagner during a recruitment drive mostly led by the paramilitary group's late chief Yevgeny Prigozhin, according to US estimates.

He promised convicts freedom if they survived six months of service — and execution if they changed their minds.

Deputy Justice Minister Olena Vysotska insists that Ukraine's version of the scheme is a fair way to achieve justice.

"We can't find any better way to rehabilitate someone in the eyes of society than to help the armed forces," she said.

The Ukrainian version advertises looser conditions, including the right for convicts to retract their applications or return to prison after deployment.

Oleg Omelchuk, 31, is among those who had a change of heart after applying to fight, choosing to stay in prison instead.

"You're a convict above anything else. That's the way it is in here, and that's the way it will be there," he said.

He said he faced no repercussions for changing his mind besides a few jokes from his fellow inmates, many of whom were still planning to join.

'Burning with impatience'

But others cannot wait to swap life behind bars for the battlefield.

"People's eyes are burning with impatience," said Volodymyr Barandich.

The tattooed 32-year-old used to serve in the army before being discharged and incarcerated for drug-dealing, though he protests his innocence.

To bide his time, Barandich shares basic combat knowledge with other inmates.

Out in the field, Roman Kyrychenko, deputy commander of the prisoners' battalion of the 92nd Assault Brigade, spoke highly of his fighters.

He said the battalion could "perform specific specialised tasks in the most dangerous areas".

A soldier from the battalion, 26-year-old Mykola Sukhotin, who had been serving a 10-year sentence for killing a man, said he was ready for combat.

"We've already passed our own school in psychological strength and motivation. We're already hardened," he said.

'Not gods of war'

Vitaliy Kononenko, who said he was sent to the Donetsk region after 20 days of training, disagreed.

"We're not gods of war, we're just normal people who happen to have stumbled," Kononenko said.

Oleg Tsvily, from the NGO Protection for Prisoners of Ukraine, said the feedback from inmates released to serve in the army had been positive overall.

But he voiced some concerns about their treatment.

"Some commanders treat even ordinary mobilised people badly, why would it be different for prisoners?" he asked.

Tsvily speculated that some commanders may enforce discipline more harshly for former inmates.

He was also critical of some of the conditions only applied to convicts, like the absence of permissions to go on leave.

Kononenko had hoped to see his family before being sent to the front and was disheartened to learn he could not.

He also said trainers treated him differently and were "not letting (the former inmates) forget" their past.

He is now focused on getting the necessary equipment for the 40 other former prisoners in his group — starting with a working car.

"I have to survive. I have to turn my life around. I have to make those people who point fingers at me saying 'convict' see that I was able to achieve something in the army."

And he had a message for any inmates seeking an easy way out.

"Guys, don't come here for freedom, you're not going to have that," Kononenko said.

"You have to have a purpose and understand what you're going to do. Otherwise, just stay out of it, stay in jail."