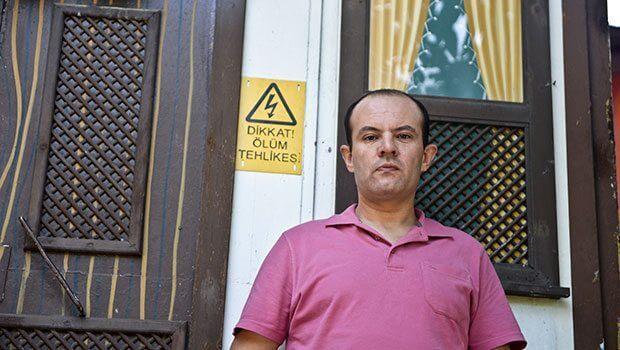

Turkish sergeant reveals how he survived ISIL

İpek İzci - ISTANBUL Photography: Selçuk Şamiloğlu Translation: Yasemin Güler

Seven months ago, Turkish Sergeant Özgür Örs fell into the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) during a confrontation at the border. He was locked in a room in Syria, only being released after he had passed an alcohol and prayer test. The Turkish army, however, recently discharged him, stating that he did not put up enough resistance against the militants.

Örs spoke about his four-day imprisonment for the first time with daily Hürriyet last week.

You were kidnapped in Kilis on Jan. 1, 2015. How did it all begin?

I was at the Pioneer Border Police Station at around six in the evening. Just as I was putting my warm clothes on, the thermal camera caught some smuggling going on in a village near the station. I was going to go on patrol anyway, so I thought I would take a look around there.

On your own?

I took a soldier along with me in case we would have to intervene. On the way there, we decided that we didn’t want them to spot us so we got off just before we arrived in the village. The vehicle left once it had dropped us off. During all this, I was constantly talking to the thermal camera operator on the phone. I called him about 10 minutes after we had been dropped off. He told me a group of seven-eight people were there.

That group of people had attempted to enter Turkey, we intervened. They had brought a tractor along with them, and its trailer appeared to be loaded with goods.

Were these “goods” ammunition?

It could have been anything. Because there was so much of it, I acted more stubbornly than I normally would have. “I won’t let this across the border,” I said. We caught one of them. He was Syrian; he had no ID or phone on him. When something like this happens, we call the military police and they then contact the prosecution office. If the prosecution office fails to find an element of crime in their actions, they give us the order to “release them.” As I thought the same would occur, I sent the person over to the Syrian side.

Chasing smugglers

And then what happened?

After that intervention, I crossed to the other side of the trench with the soldier I had brought along with me. We thought that maybe they had some goods on them and they may have dumped them on the other side of the trench. There were sacks that had been ripped open or maybe hadn’t even been sealed properly.

There were various pieces of clothing, dried legumes, cracked wheat and other materials like rice… We had been given an order regarding such situations to “deposit whatever refugee materials you find untouched on the Syrian side.” We did nothing because it was already on the Syrian side. We turned back and I called the tower watch-guard. He told me that “the tractors’ trailer is how you left it, the sacks on top are still visible.”

What was going through your mind at that moment?

I was thinking that maybe they sent these men as decoys to see if there were any soldiers posted at the border. Then they would take everything across the border once we had left. We sent for the vehicle from the station and made it look like we were leaving but got off at the other side of the village. We started to wait there. Then, thinking that two people may draw attention, I turned to the soldier and said, “I’ll go ahead, you follow me from a distance.”

Weren’t you afraid?

When we are on a mission, we lose all sense of fear, we run purely on adrenalin. At that moment, fear barely crosses your mind. I started to approach the trench and thought that the soldier was following behind but he had lost sight of me in the dark. I had walked about 200 meters. I could hear footsteps coming from somewhere in front of me, the tower watch-guard called me to warn me of approaching people. Just then a villager shone a bright light on to the path and noticed me. When he yelled out, “Soldier!” everyone on the other side ran off. I crossed over to the other side in order to check.

Do you mean over to the Syrian side?

The place I crossed over to isn’t part of Syria. Just where the trench ends is the minefield. The minefield is Turkish soil. Back in the day, controlled refugee acceptance had occurred there and deep footpaths are still visible. What I mean is that you can move around there. I had just finished the check and was about to turn back when our station commander called. He was watching the thermal camera, “Right in front of you, really close to you, three people are escaping. The goods on the other side as well as the tractors’ trailer are very close to you,” he told me.

At this point you were still alone?

Of course. Crowds are unnecessary to deal with smugglers in that area; they escape as soon as they see a soldier. “Seeing as I am so close, direct me to the precise location,” I replied, with the thought of seizing that material. I didn’t even notice how far I had gone as he directed me. I could see the tractors’ trailer standing behind a mound. As soon as I climbed on top of the mound, I found myself staring down the barrel of four Kalashnikovs.

What did you feel?

That was the first time I became alarmed. I asked myself, “What have I done?” but it was too late. “Who the hell are you?” said one of the four men harshly.

Turkish-speaking ISIL militant

He said that in Turkish?

Yes. “I’m a Turkish soldier. Who are you?” I said in reply. “We are the Islamic Army. What business do you have here?” answered another man. I told them that I was protecting the border of my country and asked them what they were doing here. During all this, my gun was pointed at them and theirs at me. One of them must have approached me as they then grabbed the gun and twisted my arm as they thrust a gun into my back and dragged me down to the ground. Another vehicle was right there but was hidden from sight thanks to the mound. They put me into the vehicle. I was taken to the gas facility across from where I was. They took my phone.

Were you blindfolded while you were in the vehicle?

Yes, they had blindfolded me. One of them came over and checked my military rank, he then spoke to someone on the phone and said, “sergeant.” Someone sitting in the front seat patted my knee and said, “Don’t take this personally, brother, we are only taking orders. We informed our superiors that we have seized you and now we must hand you over to them.” He spoke in perfect Turkish. He also assured me that “not a single hair on your head will be harmed.”

Why would he have said that, do you think?

He may have wanted to put me at ease in case I reacted violently. After all, it is the bloodiest organization in the world.

Did you try to talk with them?

Whenever I said that they were doing something wrong, or that they were making a mistake, a man sitting next to me would yell at me to keep quiet and would then shove my head down and stop me from talking. They all spoke Turkish though. After travelling for about 45 minutes with my eyes blindfolded, they put me in a jail type of building that had no electricity. I sat in a cell, still blindfolded. A large group entered, one of them went behind me and another in front of me. They asked me my name and surname, my military rank and my reason for entering Islamic lands.

And how did you reply?

The one standing in front of me directed me, “Why did you enter the Islamic lands, did you enter them by accident?” he asked. It was like he wanted me to give him that answer. I told them that I had entered the land by accident. Then they asked if I had drunk any alcohol to which I replied, “I don’t drink alcohol.” They left the cell. Soon after that they put me in another vehicle. I was still blindfolded; two people got in the front and two others sat beside me. We drove for quite a while; for three hours I think. It was almost morning when they put me in the room of some house. They had handcuffed me and I stayed there for four days.

‘Praying correctly saved my life’

Could you tell us how that first day went?One of the men crossed his chest as we were entering the house, “Christian?” he asked as he looked at me. “No, Muslim,” I said hastily. “OK then, good,” he said. After the afternoon call to prayer, one of them came up to me and said, “Pray.” Another one of them sat and watched me as I prayed. He was watching how I was praying. If I hadn’t been a real Muslim, if I hadn’t been able to pray correctly, I would surely have been executed. Praying is what saved me in the end.

How did they behave toward you after you prayed?

Once the prayer was over, the man watching said, “The afternoon prayer is four rakaahs, you performed eight. You’re a guest.” I told him that yes, I was a guest but I didn’t know how long I would be staying. After that he left and locked the door.

Did you see any others being held captive?

No, I didn’t.

Were you afraid?

Of course I was afraid. I knew what sort of organization was holding me captive. I kept thinking about what they would do to me. I can’t not say this; even while I was there dealing with everything, I was worried about what punishment I would get upon my return.

Seriously?

Yes, really I was. Mostly I was worried about my family, but I was also worried about what punishment I would get.

What was the place like where you stayed for four days?

The walls were painted white, [and there was] a single sponge mattress on top of a yellow-blue plastic wicker bed. There were also two blankets, four or five other plastic wicker beds and a wardrobe. I didn’t see any rooms other than the one I was kept in.

Was the room clean?

The cleanliness of the room was adequate.

What did the militants wear?

They generally wore dark-colored shalwars and shirts along with trainers or slippers.

Did you ever see their faces?

They always had ski masks on, I only ever saw their eyes. They had Kalashnikovs and pistols.

What did you eat or drink there?

On the first day, they gave me chicken with rice for lunch and dinner. After that, homemade meals like pea-and-meat casseroles were served, and one evening they brought me something that was similar to a kebab.

For breakfast, they gave me jam and melted cheese. A couple of times I was given an apple and then an orange. The portions were filling. Drinking water was given in 1.5-liter bottles and they were topped up frequently.

Path to freedom

Did they stay in the same room as you?

They stayed in another room. They only came in my room during food and prayer times and also when I had to relieve myself. Even then they only spoke one word, “prayer,” “toilet” or “food.” I was always waiting with my handcuffs on.

How did they talk among themselves?

I never witnessed them talking among themselves.

What about the toilet facilities?When I had to go, I would knock on the door and they would open it.

Did they give you any clothes?

The day before I was handed over they brought a grey tracksuit and told me to put it on. Until then I had been wearing my uniform.

How did your imprisonment end?

They handed me over to authorities four days later at the Akçakale border. I don’t know who they spoke to or what they spoke about.

Did they say anything to you during the handover?

There was no speaking during the ride there, but as I was getting out of the vehicle, one man said, “Infidel Turk, repent!” and then I was handed over.

Who rescued you?

I have no information on that subject.

How can you not know who it was that saved you?

Two men met me at the Akçakale border, they told me that they were from the Turkish National Intelligence Organization (MİT) and that I had been rescued as a result of an operation the MİT had carried out. They welcomed me back to my country, then delivered me to the military authorities.

And the first thing you did once you were free?

I smoked a cigarette because I hadn’t been able to for four days. Then I called my wife.

What sort of mood were you in?I was like a rabbit caught in headlights; I was like a robot. They told me to go; I went. They told me to come; I came. Then when I got home, I took my son and daughter outside to play in the snow.

“Soldier kidnapped because he stepped on ISIL’s toes” was a headline that had been written about you. Do you have any comment about that?

This incident was nothing more than a coincidence. It wasn’t planned nor was I pulled into a trap. No one could have known that they would have been people passing through there or that I was going to be on duty. Neither could anyone know that I would have travelled that far. Everything happened because of my recklessness.

Supposed to die, not surrender

After the incident, you were discharged ex officio with the justification that you damaged the reputation of the government and the Turkish Armed Forces.

That’s a polite way of saying that I was fired.

Do you have a salary or benefits and can you claim a retirement bonus?No.

How much is your current income?

I have no income until I manage to get a new job. Zero. I don’t even have the luxury of choosing a job. I have two children and a wife to look after. I would even work on a construction site. I have filed a lawsuit against the Military High Administrative Court for the annulment of my employment by the judgement of the High Disciplinary Board. The first hearing is in 10 months. I always prefer to look at things on the bright side. I think that I will be able to return to my job.

What was the first thing you thought of when you heard the final decision?

“How will I be able to support my family now?” People may think that soldiers earn loads of money, but during my 11 years of employment I have only managed to buy a car. I have no other savings.

How were you informed that you had been discharged ex officio?

There is a website “kara.net.” It was announced on that website that I had been dispatched to the retirement bureau. I did some research and found out that I was going to be discharged. I received a written statement 10 days after that.

‘If you are free, why didn’t you die?’

One of the crimes that the Turkish Armed Forces ascribed to you was that you didn’t resist the forces of ISIL.

They held a gun to my head, so I defended my right to live. All that has been going on since my return makes me think that what they really want to say is, “If you’re free; why didn’t you die, you were supposed to die.” You either react with your reflexes when you have a gun to your head; or you don’t. The image of my child floated in front of my eyes and I couldn’t [risk dying].

And another was that it fell into the hands of the press and that you were used for ISIL propaganda.

That was something that developed beyond my control.

Do you think that the same process would have happened if you had been of a higher rank than a sergeant?If I had been an officer I wouldn’t even have been dispatched to the High Disciplinary Board. There are officers that go to the High Disciplinary Board to give statements about different crimes; sexual assault, bribery, theft. Those men get discharged but they still get to keep the title of their current ranks. A rapist lieutenant gets discharged as a lieutenant. But I am discharged as a private… It’s unfair.

Which incident offended you most? That you were imprisoned by ISIL or that you were dismissed from the Turkish Armed Forces as a result of your abduction?

Definitely my dismissal. The conditions at that time pushed me to being imprisoned but I never thought that I would be punished in such a severe way. I am still in shock.

‘For the love I have for my country’

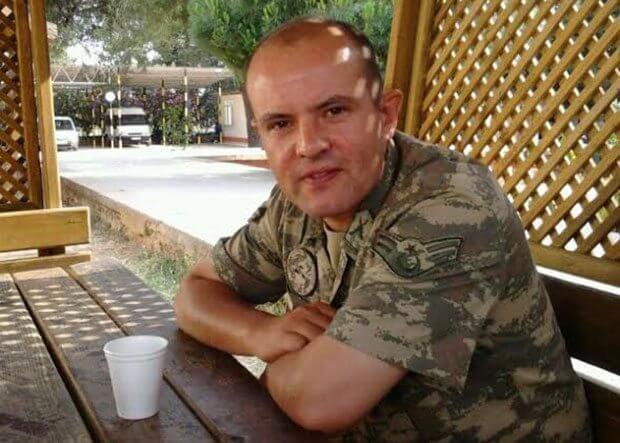

Why did you choose a career in the military?Primarily because of the economic advantages. I preferred to work for the army which has primary benefits rather than working somewhere else on a minimum wage. I started in 2004 and became a non-commissioned sergeant in 2011.

Did you ever consider leaving the job during that period?

Of course. You can predict what will happen with this sort of job. There can be sudden outbursts of anger but a couple of days later you calm down.

Did you like your job, until you were kicked out of the army?

This job isn’t like any other civil servant jobs. You don’t have weekends, or proper working hours, no holidays or bank holidays. This isn’t the type of job you do just for the money; you’ve got to have a deep love for your country.

If you win the lawsuit for the annulment of your discharge, do you think you will have the same motivation for your job as before?

Of course. If I went there right now and experienced the same thing, I would do the same as before. I worked for four years in southeastern Turkey. If I were to run from this job, I would have run while I was there. I never even laid eyes on a bed or mattress while I was there, let alone sleep on one. I fell into an [outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party] PKK ambush from a height of 15 meters on July 15, 2006, and had magazine rounds shot at me from 15 meters. If I were going to quit, that’s when I would have quit.

Redefining the concept of captivity for soldiers

Sgt. Özgür Örs’ dishonorable discharge for failing to fight sufficiently against his abduction by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) is “unacceptable,” according to the soldier’s lawyer, Mehmet Erkan Akkuş.

“The claim that the imprisonment of my client, who acted within the knowledge of his duty, damaged the reputation of the Turkish Armed Forces and the government is unacceptable. We have been forced to redefine the term of imprisonment due to my clients’ discharge from the Turkish Armed Forces and the interrogation he went through from his sequential supervisors. he Retired Non-Commissioned Officers Association of Turkey, who has a million members, fully supports Özgür Örs. We have filed a lawsuit against the Military High Administrative Court (AYİM) for the annulment of the discharge. Özgür defended his right to live as he had a gun against his forehead. The universal human right can’t be made into an appetizer for diplomacy and politics,” Akkuş said.

Seven months ago, Turkish Sergeant Özgür Örs fell into the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) during a confrontation at the border. He was locked in a room in Syria, only being released after he had passed an alcohol and prayer test. The Turkish army, however, recently discharged him, stating that he did not put up enough resistance against the militants.

Seven months ago, Turkish Sergeant Özgür Örs fell into the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) during a confrontation at the border. He was locked in a room in Syria, only being released after he had passed an alcohol and prayer test. The Turkish army, however, recently discharged him, stating that he did not put up enough resistance against the militants.