Turkish designers flourish despite attacks on their ‘sanity’

Emre KIZILKAYA - ekizilkaya@hurriyet.com.tr

2014 was a year in which the strengths and weaknesses of Turkish design were seen clearly in regard to its tradition and practice, which sometimes shone with brilliant examples and at other times bedevilled people with conditions that challenged the “sanity” of innovators.

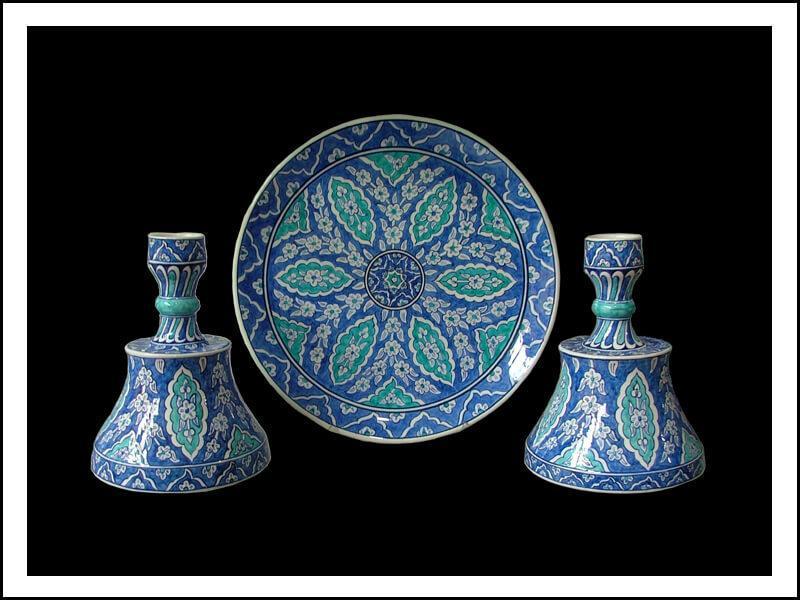

From “

nazar” beads to İznik tiles and ceramics (below), the Turkish design tradition in visual arts is deep and rich. It gave birth to masterpieces like

the Selimiye Mosque in architecture and “

The Tortoise Trainer” in painting.

These were products of a traditionally innovative nation, who achieved

sustained unpowered flights in the 17th century despite a political system that largely suppressed any novelty as a potential risk to stability.

Ottoman figures like Hezarfen Ahmed Çelebi and Lagari Hasan Çelebi were the predecessors of Yves Rossy, the modern "rocket man" from Switzerland.

In several instances, wars have been the times that innovations helped – or harmed – Turks. From bows to artillery, some Turkish weapons were the most advanced ones for several centuries in many regions, before they were rendered obsolete by other nations that got ahead, particularly after the Industrial Revolution.

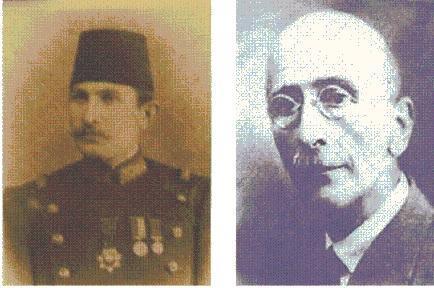

In 1897, only two years after their discovery by German scientist Wilhelm Röntgen, X-Rays were used by Turkish military doctors for the first time in the world when they resorted to this new technique for a diagnosis on Ottoman soldiers who were wounded while fighting against rebellious Greeks.

The pioneers of radiology in Turkey are Dr. Esad Fevzi (1874-1901) and Dr. M. Rıfat Osman (1879-1921) who used X-Rays for the first time in the battlefield.

In 1911, the Italian army conducted the world’s first aerial bombing against Turkish troops in Libya. In return, the Turkish army marked a first in the world by shooting down an aeroplane with field artillery and rifle fire due to a lack of anti-aircraft weapons then.

Captain Riccardo Moizo, the pilot of the Italian military plane "Nieuport IV" had became the first pilot who were held captive by the enemy --the Turks who forced him to land his damaged plane in Libya in 1911.

Innovation in processes, instead of products, is a tradition in Turkey for other areas, too, as seen in the ways of making Turkish coffee, tea, ayran, rakı and döner, as

sources of

inspiration for the world.

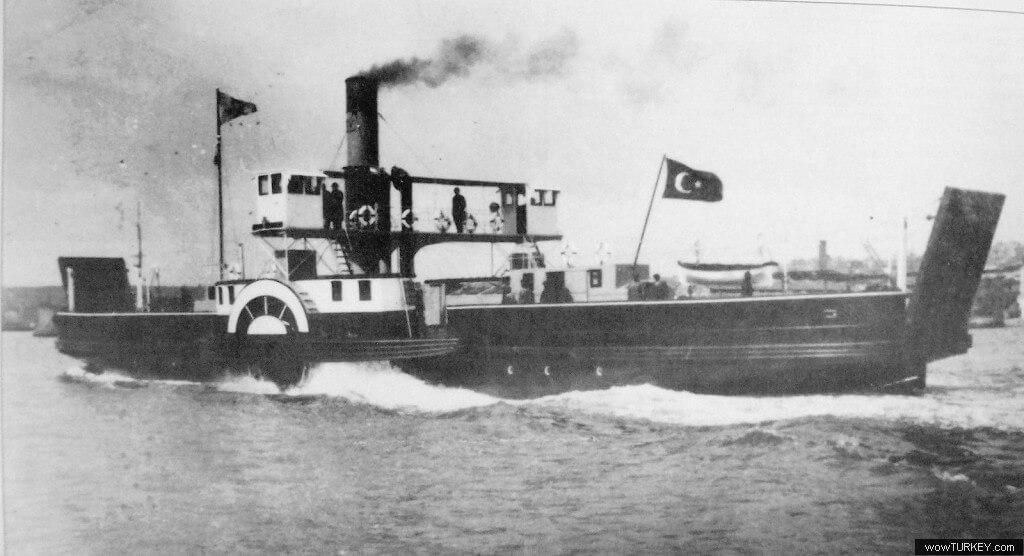

Indeed, Turks were particularly successful in discovering new functions for existing products, mostly for economic reasons. They built “Suhulet,” the world’s first ferry that could carry cars in 1871, and they turned taxis into mass transit vehicles in the form of the “dolmuş” in 1929.

Steam-powered "Suhulet" was a unique design for the 19th century

Each day, many individuals in Turkey still come up with innovative ideas and products despite the continuing lack of a coherent system that nurtures innovation.

Take Mustafa Karasungur, a villager from eastern Turkey, who

created an “anti-bear robot” last summer, becoming a subject of praise and mockery on social media.

Since the mid-19th century, when the first industrial and artistic design schools were founded in Turkey, this bottom-up tradition has been gradually institutionalized and professionalized in a top-down way. Now, a new breed of Turkish designers keeps building bridges with this history despite all the odds.

Zeynep Fadıllıoglu proved herself as an example in architecture when

she designed the interior space of the Şakirin Mosque. In visual arts,

Murat Palta linked Ottoman miniatures to Hollywood, as reported by the international media last year.

2014 saw many other interesting Turkish designs, like...

The iPhone app that

turns sketches into tappable mobile app “prototypes” by Marvel, co-founded by Murat Mutlu...

Karsan’s

latest taxi design for London streets...

Hasan Kale’s new “micro paintings...”

Nur Yıldırım’s

SkinAir, a protective neckpiece for comfortable breathing...

Koray Özgen’s

Asteroid Pendant Light...

And

Monochroma, a video game created by Istanbul-based developer Nowhere Studios.

Notable Turkish designs in several industries, including defence and fashion, were so numerous in 2014 that they are not counted here, although the total number of innovations in Turkey is still far behind the countries that invest much more in these areas.

But arguably the most remarkable Turkish design this past year was from the medical sector, just like it has been when

Ankaferd BloodStopper, a plant-based antihemorrhagic that is now used in hospitals and ambulances in Turkey to stop external bleeding, was introduced a few years ago.

The most lauded Turkish design of 2014 was a product of 3D-printed cast that uses ultrasound to speed up bone healing:

Osteoid.

After winning the 2014 Golden A Design Award in the 3D-Printed Forms and Products Design category with his unique concept, Turkish designer Deniz Karaşahin told the Hürriyet Daily News that he wanted to enter into a competition with a “useful” product from an industry with a high rate of possibility for technology transfer, like medicine and space/aeronautics.

“I started to work on Osteoid, although I had not broken my arm,” he added.

As a 28-year-old designer who was born in İzmir and graduated from İzmir Economy University’s industrial design major in 2008, Karaşahin had previously worked as a lecturer in Turkish universities and founded his company, dk design, in France.

“It was easy to start there as I also carry a French passport,” he said.

Beside its medical functionality, Osteoid’s 3D-printed cast brings about an aesthetics sensibility: Not only does it heal the bone faster, but it also looks cooler than conventional plaster casts. One may find a parallel between Osteoid’s ventilation holes with the diverse geometric patterns of Turkish and Islamic art.

Karaşahin thinks that Turkey is a “sui generis” country. For designers, it presents opportunities, like low labor costs in the production of boutique objects.

“However, besides this advantage, the environment that the domestic market dynamics create is so bad that it becomes ridiculous to judge on the appreciated value of labor,” he observed.

As such, Turkey may already be facing a brain drain with talents like Karaşahin immigrating to better design environments, like France or elsewhere. The young designer, on the other hand, does not believe that this is the risk.

“With 3D printing and other developing technologies, a lot of things will change anyway. What is important is to understand the change and adapt yourself. The place that you physically are is irrelevant,” he said.

Karaşahin believes that the online accessibility of more and more information, as well as concepts like crowdfunding, venture and incentives, make it “redundant” to live and work in a foreign country.

Today’s polarized political atmosphere and sometimes maddening social tensions in Turkey, however, apparently affect designers, too, mostly in negative ways.

“The only important factor is being in an environment where you won’t lose your sanity and can focus when you go out or turn on your television, at least being able to protect yourself,” Karaşahin concluded.

2014 was a year in which the strengths and weaknesses of Turkish design were seen clearly in regard to its tradition and practice, which sometimes shone with brilliant examples and at other times bedevilled people with conditions that challenged the “sanity” of innovators.

2014 was a year in which the strengths and weaknesses of Turkish design were seen clearly in regard to its tradition and practice, which sometimes shone with brilliant examples and at other times bedevilled people with conditions that challenged the “sanity” of innovators.