Turkey needs a new social contract

Aykan Erdemir*

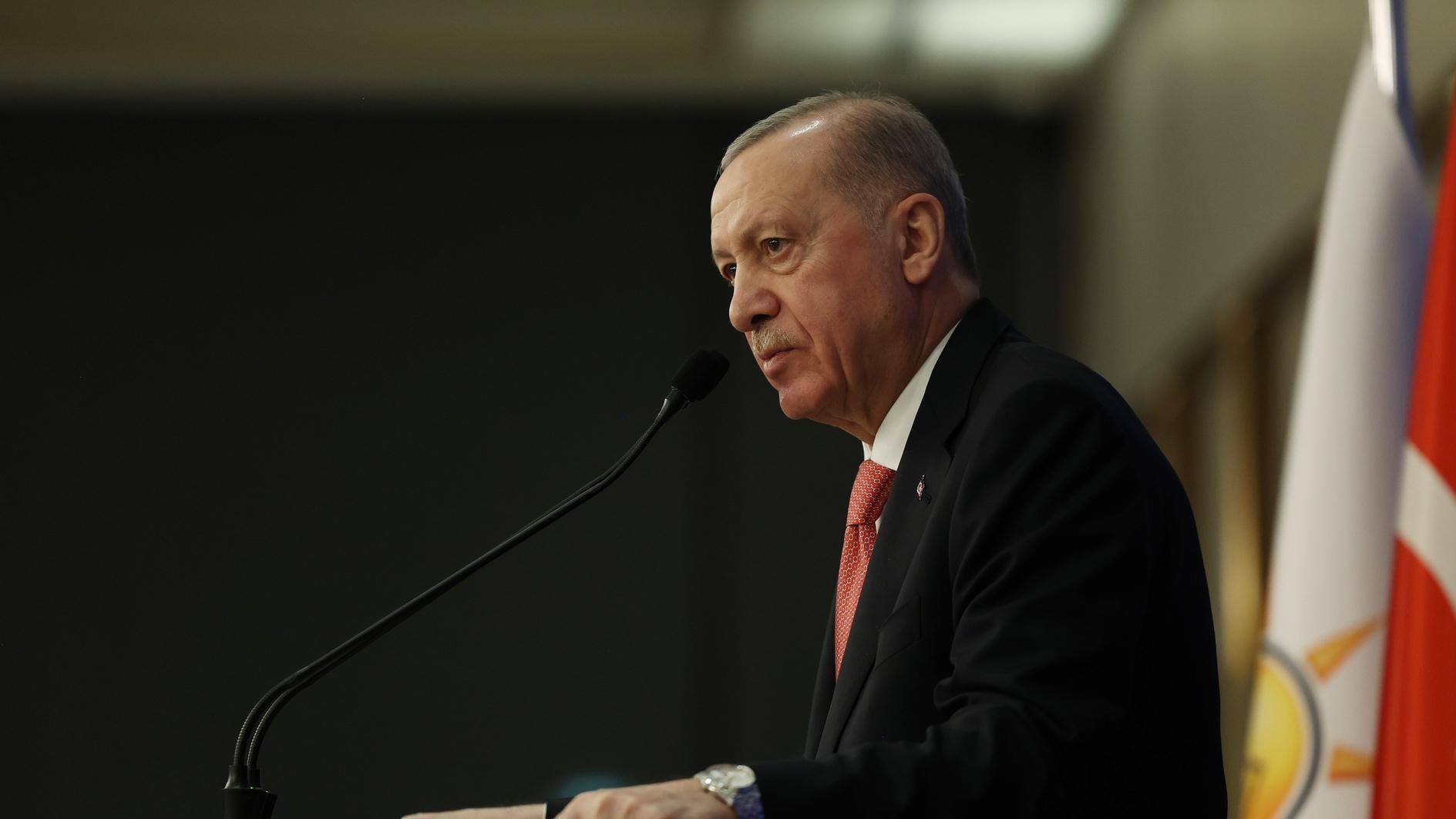

A decade ago, Turkey was hailed as a success story due to its booming economy, proactive foreign policy and progress toward EU membership. Today the country is making headlines for different reasons: Frequent terror attacks, rising polarization, deepening diplomatic isolation and a flagging economy. Ankara urgently needs to reverse course. This requires, first and foremost, a new social contract. Unfortunately, Turkey’s failed attempts for a new bill of rights seem to have eroded enthusiasm for any further effort. Much of the Turkish public still recognizes the need to amend the current constitution, but there are no viable strategies to overcome the political and social constraints that have thus far prevented a compromise.What further undermines attempts at finding common ground is Turkey’s transition to a de facto presidential system, amid President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s refusal since 2014 to be an impartial president as stipulated by the constitution. Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım, who replaced Ahmet Davutoğlu at the Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) extraordinary congress in May, stated in his first address to party delegates that his most important mission was to “legalize” Erdoğan’s newfound political role “by changing the constitution.”

The president’s open disregard for the constitution has become a key point in the constitutional debates. The Democracy First Initiative – comprised of 237 signatories, including Republican People’s Party (CHP) and Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) legislators, as well as political dissidents – issued an open letter in May stating that it was not possible to draft a new constitution under the current political circumstances, and criticizing the de facto “imposition of a presidential system.”

After the failure of the cross-party constitutional panels in 2013 and 2016, and the subsequent disputes over the presidential system, Turkey seems to have come full circle, back to the debates held in 2011 about the need to “clear the path” for a new constitution by first amending the country’s anti-democratic laws, much as Spain did following the death of military dictator Francisco Franco in 1975. Then, as now, proponents of this strategy suggest that “clearing the path” should be given priority over attempts to draft a new constitution.

Under the current circumstances, the opposition’s almost complete loss of interest in a new constitution will make the task of consensus-building more challenging than ever. Opposition parties will likely perceive any AKP offer to restart the talks as yet another ploy to grant legitimacy to Erdoğan’s de facto rule as an executive president. The opposition’s skepticism, in turn, will force the AKP to find majoritarian, non-consensual tactics to legalize that de facto situation.

It is, nevertheless, still possible to make progress with the constitution if Turkey replaces its current fixation with the wholesale drafting of a new constitution with an incremental strategy. The 1982 constitution, for example, was amended seven times before the AKP came to power in November 2002, leading to the revision of almost one-third of its articles. Under AKP rule, the constitution has been amended 11 more times, resulting in revisions to 57 articles. More than half the articles of the 1982 constitution have been amended over the course of the last 34 years, including key changes that once helped bring Turkish legislation in line with EU norms.

As a deeply divided society, Turkey needs an incrementalist approach to overcome social polarization and political impasse. Instead of a new constitution drafted from scratch, Turkish citizens need to gradually build a new understanding, by laying out the fundamental principles that will allow them to coexist peacefully despite differences. This, however, is only possible through deliberation, compromise, and the building of trust.

In Turkey’s current polarized political context, however, the constitutional deadlock is likely to be prolonged as more pressing challenges, such as the escalation of violence and foreign policy crises, take priority over civil rights and liberties. In Turkey, once again, the rights of the individual will have to wait.

*Dr. Aykan Erdemir is a former member of the Turkish parliament, faculty member at Bilkent University and a senior fellow at the Washington-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD).