The winner in China's panda diplomacy: The pandas themselves

WASHINGTON

China's panda diplomacy may have one true winner: The pandas themselves.

Decades after Beijing began working with zoos in the U.S. and Europe to protect the species, the number of giant pandas in the wild has risen to 1,900, up from about 1,100 in the 1980s, and they are no longer considered “at risk” of extinction but have been given the safer status of “vulnerable."

Americans can take some credit for this accomplishment, because conserving the species is not purely a Chinese undertaking but a global effort where U.S. scientists and researchers have played a critical role.

“We carry out scientific and research cooperation with San Diego Zoo and the zoo in Washington in the U.S., as well as European countries. They are more advanced in aspects such as veterinary medicine, genetics and vaccination, and we learn from them,” said Zhang Hemin, chief expert at the China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda in the southwestern Chinese city of Ya'an.

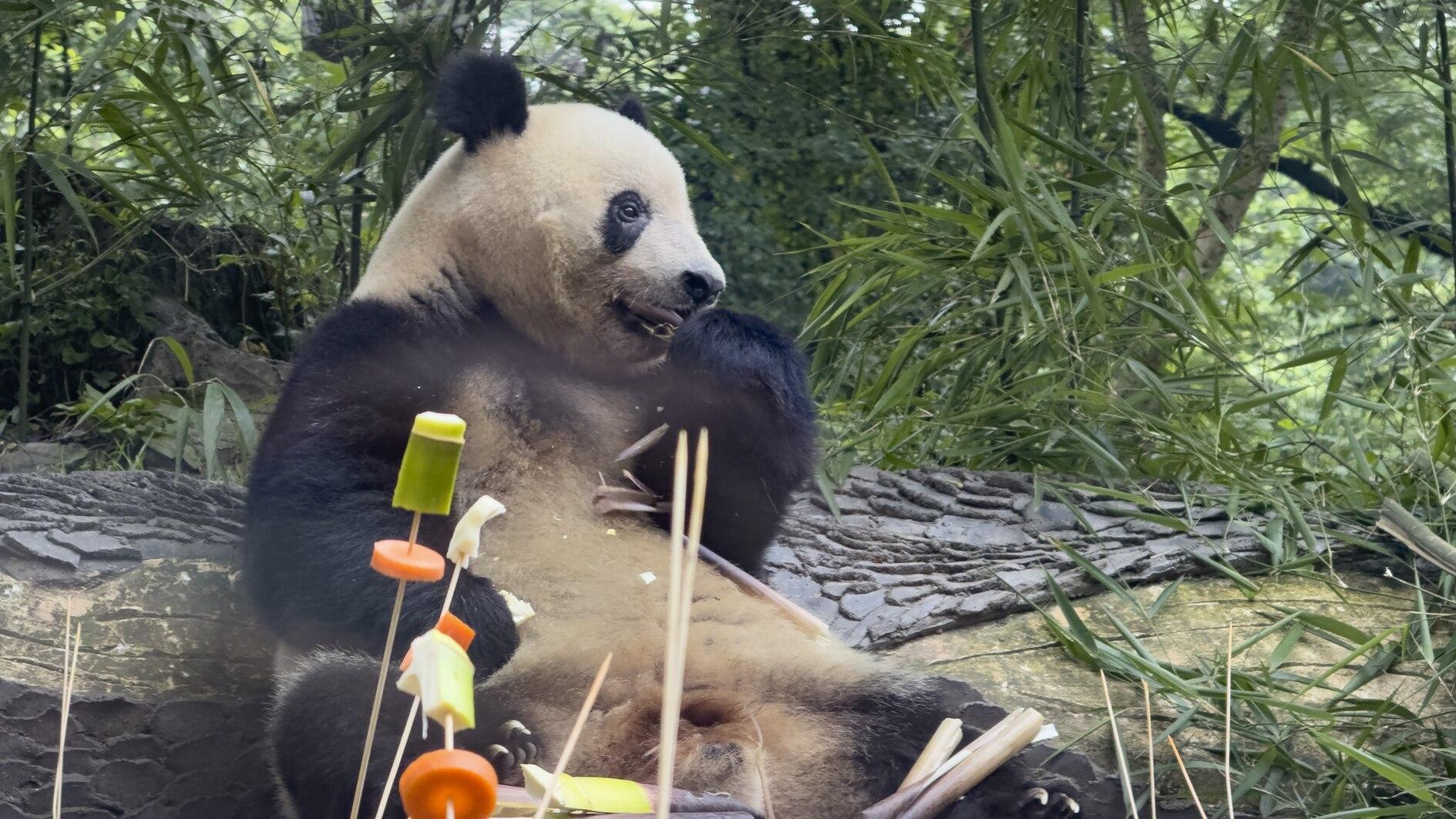

Zhang spoke to journalists during a recent government-organized media tour at the Ya’an Bifengxia Panda Base, home to 66 pandas that lolled about and chomped on stalks of bamboo in a tranquil setting rich with vegetation.

China's giant panda loan program has long been known as a tool of Beijing's soft-power diplomacy, but its conservation significance could have been an important reason Beijing is renewing its cooperation with U.S. zoos and sending new pairs of pandas at a time of otherwise sour relations.

A pair of pandas that arrived at the San Diego Zoo in June will debut to the public after several weeks of acclimation. Another pair will c ome to the Smithsonian's National Zoo later this year, and a third pair will settle in the San Francisco Zoo in the near future.

Their arrivals herald a new round of giant panda conservation cooperation, after the agreements from the first round — which began around 1998 — ended in recent years. The ongoing difficulties in the U.S.-China relationship fueled worries Beijing was retreating from sending pandas abroad, but President Xi Jinping in November dispelled the worries with an announcement during a U.S. visit last year.

It is a brilliant move to soften China’s image among Americans but is unlikely to change U.S. policy, said Barbara K. Bodine, a former ambassador who is now a professor in the practice of diplomacy at Georgetown University.

“If they are to project China not as a big, threatening country, they send several pairs of overstuffed plush toys,” she said. “Pandas are cute, fat and fluffy. They sit all day and eat bamboos, then China is kind of this cuddly and fluffy country. It’s the best signaling.”

But “it doesn’t change the political discussion one whit,” Bodine said. “Public diplomacy can do only so much. It does not change the geopolitical, economic calculations. People don’t go home after the zoo to be OK for the U.S. to be flooded with cheap electric vehicles from the panda land.”

Conservation, however, is keeping the two sides working together.

Zhang said there are benefits from sending pandas overseas.

“Pandas temporarily living abroad raises humans’ awareness of preservation, and promotes attention to our planet and the protection of biodiversity,” Zhang said. “Why isn't it good?”

Zhang said pandas sent overseas have been selected for their good genes. “They have very high hereditary values. If they bear offspring, the cubs also will have very high hereditary values,” he said.

While Western research leads in genetic studies, China excels at feeding and behavioral training, he said. “It’s mutually complementary,” Zhang said. The ultimate goal, researchers say, is to help the bears return to the wild and survive, and a larger captive-bred panda population is the foundation for that effort.

The first giant pandas sent abroad were more gestures of goodwill than conservation pioneers from a Chinese communist government seeking to normalize its relations with the West. Beijing gave a pair of pandas — Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing — to the U.S. following President Richard Nixon's historic visit to China in 1972 and then other pandas to other countries, including Japan, France, Britain and Germany, over the next decade.

When the panda population dwindled in the 1980s, Beijing stopped gifting pandas but turned to more lucrative short-term leasing then longer-term collaboration with foreign zoos on research and breeding.

Under this kind of new arrangement, Mei Xiang and Tian Tian arrived at the National Zoo in 2000, with the ultimate goal of saving giant pandas in the wild. Over the 23 years Mei Xiang lived in the U.S. capital, she gave birth to four living cubs: Tai Shan in 2005, Bao Bao in 2013, Bei Bei in 2015, and Xiao Qi Ji in 2020. All have been returned to China.

Bei Bei, sent to China in 2019 , walked over to a row of lined-up bamboo shoots last month, picked one up with his teeth and sat down to eat it as a cluster of visitors looked on at the Ya’an Bifengxia Panda Base. Staff described the nearly 9-year-old male as sociable.

Smithsonian scientists have been working to “unravel the mysteries of panda biology and behavior, gaining crucial insights into their nutritional needs, reproductive habits and genetic diversity,” the National Zoo says in its literature on the panda program.

Pandas born overseas can face a language barrier when they are sent to China, said Li Xiaoyan, the keeper for Bei Bei and two other bears from abroad.

“Some pandas may adapt very quickly and easily upon return, while others need a long time to adjust to a new environment, especially human factors such as language,” Li said. "Overseas, foreign languages are spoken. In China it’s Chinese that’s used, and even Sichuanese and the Ya’an dialect.”