‘The Soda Seller’ out to please a diverse audience

Emrah Güler - ANKARA

There is something for all kinds of moviegoers in this week’s new release, director Yüksel Aksu’s period drama “İftarlık Gazoz” (The Soda Seller). The film will keep the weekend soda-and-popcorn crowd entertained, while some of the (if not all) art-house audience will likely praise the acting and cinematography. The coming-of-age story at the heart of the film is the right mixture of warm and funny, set to appeal to a diverse audience.

Those who have remembered and missed the more personal and heartfelt stories of actor/director/comedian Cem Yılmaz after his recent blockbuster “Ali Baba ve 7 Cüceler” (Ali Baba and the 7 Dwarfs) will probably have watched the film by now. Older generations will enjoy the 1970s’ nostalgia on provincial life, reminiscing about the good old times. Others will enjoy the romanticized political storylines.

The idyllic Aegean region is a familiar place for director and writer Aksu. It is his hometown and the setting to his debut and sophomore features, 2006’s “Dondurmam Gaymak” (Ice Cream, I Scream), Turkey’s official submission for 79th Academy Awards’ Best Foreign Language Film, and “Entelköy Efeköy’e Karşı” (Ecotopia).

In “İftarlık Gazoz,” we are once again taken to a small town in the Aegean. It’s the mid-1970s, and at the center of the film is a boy on the threshold of his teen years, Adem (Berat Efe Parlar). Smart, savvy and responsible, Adem decides to spend his summer working as the apprentice of the local soda seller, Cibar Kemal (Cem Yılmaz).

Coming-of-age in the Aegean

The month of Ramadan is around the corner, and this means two different things for the boy and his mentor. It’s that time of the year when business booms for Cibar Kemal, as the fasting crowd will run for the soda when they break their fast, and as for Adem, it’s time to do the sensible and the expected in his small, wandering mind: Start his journey of month-long fasting.

Adem is too young to fast, and the Aegean is too hot to fast. So begins Adem’s arduous quest despite the objections of his family. Two major forces drive Adem to continue: The fact that his young crush Berna is also fasting and that atonement for breaking the fast is 61 more days of fasting.

Adem’s younger years intertwine with later years, when he goes on a hunger strike after being jailed following the 1980 military coup. The will to go on without food and water take different motivations in the two different stages in Adem’s life. Politics is always on the background throughout the film, as another older role model for Adem, Hasan (Yılmaz Bayraktar), fiercely tries to unionize the tobacco workers in the field, which basically is most of the town.

Aksu is well aware that at the heart of his movie is a little boy’s story, getting one of the best performances from a child actor in recent history. Ümmü Putgil, who plays Adem’s mother, is also the acting coach for the young actor. Aksu specifically wanted to work with Putgil, bringing her from the U.K. for this film. His insistence seems to have paid off, as the chemistry between the mother and the child are brimming from the screen.

Children on screen

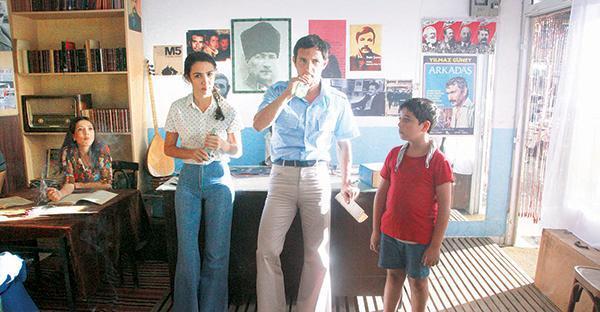

A careful audience will notice the two film posters in the background in one of the scenes. The posters are of Charlie Chaplin’s 1921 classic “The Kid” and another classic from Turkish cinema, 1973’s “Canım Kardeşim” (My Dear Brother). Both are stories of children, one on the relationship between a man and an abandoned child, the other about a man and his terminally ill brother.

Melodramas featuring children have been a familiar picture in Turkish cinema since the 1950s; children and their misfortune were a major storyline more often bordering on emotional exploitation until the 1970s. The tragedies children had to face on screen were always too big for their short lives. Most of them were abandoned by their parents, often born out of wedlock to ultimate shunning, left on the streets to fend on their own.

While child characters continued being a major presence in Turkish cinema in later decades, they became more realistic, displaying more professional acting. Some examples are Tunç Başaran’s “Uçurtmayı Vurmasınlar” (Don’t Let Them Shoot the Kite) from 1989, a child’s accounts of life in prison; Çağan Irmak’s 2005 tearjerker “Babam ve Oğlum” (My Father and My Son), the account of the coup through the eyes of different generations of men; and Reha Erdem’s “Beş Vakit” (Five Times A Day) from 2006, a look at life at its slowest in a village through the lives of children.

The more recent example is “Sivas,” director Kaan Müjdeci’s debut feature from last year and Turkey’s official entry into the Academy Awards Best Foreign Language Film this year. The story of an 11-year-old boy and an Anatolian shepherd dog garnered many awards in the international festival circuit, including the Special Jury Prize and an award for its young actor at the Venice Film Festival. Both “Sivas” and this week’s “İftarlık Gazoz” are remarkable examples of accomplished acting by children.

There is something for all kinds of moviegoers in this week’s new release, director Yüksel Aksu’s period drama “İftarlık Gazoz” (The Soda Seller). The film will keep the weekend soda-and-popcorn crowd entertained, while some of the (if not all) art-house audience will likely praise the acting and cinematography. The coming-of-age story at the heart of the film is the right mixture of warm and funny, set to appeal to a diverse audience.

There is something for all kinds of moviegoers in this week’s new release, director Yüksel Aksu’s period drama “İftarlık Gazoz” (The Soda Seller). The film will keep the weekend soda-and-popcorn crowd entertained, while some of the (if not all) art-house audience will likely praise the acting and cinematography. The coming-of-age story at the heart of the film is the right mixture of warm and funny, set to appeal to a diverse audience.