The plague: A pox upon the houses of everyone

Niki Gamm

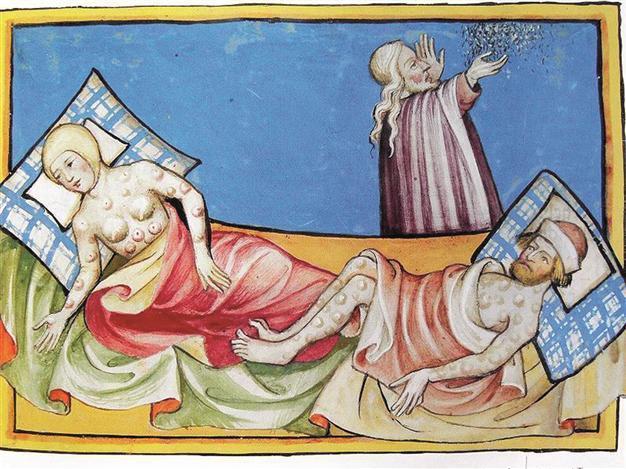

Bishop blessing plague victims.

Among the earliest mentions of plague are the 10 plagues that struck Egypt in approximately the sixth century B.C., and they are supposed to have led to the pharaoh of the time letting the Israelites leave his country. It is, however, not clear what type of plague it might be that would only kill firstborn sons and not affect other members of the family. Plague is mentioned one other time in the Old Testament related to King David; at that time 70,000 people are supposed to have died in a three-day period.

Usually plague is defined as a contagious bacterial disease characterized by fever and delirium caused initially by infected fleas and later spread from person to person – today’s Ebola virus in West Africa immediately comes to mind. The latest speculation is that it has been spread via bats.

When we say plague, what leaps to mind is the bubonic plague of the Middle Ages which is thought to have started in Central Asia or China and spread west and south from there. Millions upon millions died because there was no cure for such a disease, the cause of which no one knew at the time.

The bubonic plague was apparently spread via commerce along the Silk Road and/or invading armies. The first known cases of bubonic plague occurred in the 1330s in China and spread to the Crimea by 1343. The year 1347 was a year in which Constantinople registered the plague and Genoese vessels brought the disease from there where merchants had been engaged in commerce. These traders docked in Messina, Sicily, in October of that year and were driven off by the townsfolk but not before they had spread the disease to land. By August 1348, the plague had reached England. In the Middle East, Alexandria in Egypt was first hit in 1347 and from there it spread east and north along the Mediterranean coast. It was reported in Mecca and Mosul in 1349.

Europe lost around 20 million people to the plague in the five years following the arrival of the boats at Sicily. Estimates worldwide suggest that as many as 200 million may have died; half of the population of Europe is said to have perished. People fled but couldn’t escape because it traveled so quickly, finally reaching Russia in the north (1351) and Africa in the south.

As the 14th century Italian author and poet Giovanni Boccaccio who lived through the plague wrote: “What more can be said except that the cruelty of heaven (and perhaps in part of humankind as well) was such that between March and July, thanks to the force of the plague and the fear that led the healthy to abandon the sick, more than 100,000 people died within the walls of Florence. Before the deaths began, who would have imagined the city even held so many people? Oh, how many great palazzi, how many lovely houses, how many noble dwellings once full of families, of lords and ladies, were emptied down to the lowest servant? Oh, how many memorable pedigrees, ample estates and renowned fortunes were left without a worthy heir? How many valiant men, lovely ladies and handsome youths whom even Galen, Hippocrates and Aesculapius would have judged to be in perfect health, dined with their family, companions and friends in the morning and then in the evening with their ancestors in the other world?” (Translated by David Barr).

After five years, the plague in Europe abated, only to recur some 10 years later and sporadically after that until the 19th century. Today bubonic plague can be cured with simple antibiotics.

The plague and Istanbul

The plague and IstanbulThe first record of plague in Istanbul appears during the reign of the Emperor Justinian II (r. 540-590) and is discussed in Procopius’ “Secret History” among other sources. It is supposed to have reached the city from Egypt in 541-542 AD as a result of the many ships carrying grain from the latter. From the descriptions of the symptoms, it was quite clearly bubonic plague. The disease spread through the Eastern Roman Empire, east into the Sassanid Empire and to ports along the Mediterranean. One contemporary estimate was that 100 million people died.

A study published last year in “The Lancet Infectious Diseases” journal, showed that the strain of plague that struck sixth-century Constantinople was not the same as that which appeared in the 14th century. John VI Cantacuzenus was new to the throne in Constantinople in 1347 when the Genoese ships brought the plague from the Crimea. When the plague finally ran its course the next year, it is estimated that a third of the city’s population had died of the disease.

Very little is known of the effect the spreading plague had on the early Ottomans. They were allies of the Genoese and the Byzantines so one would expect that the plague would be found among the Turks as well. After all Cantacuzenus’ daughter was married to Sultan Orhan and the former also hired Turkish mercenaries to fight for him.

Although the plague of 1347 died down, it returned in 1361-2 and continued to return every few years until the 19th century. In fact there seems to be no real break in the incidence of plague because it affected various towns and cities throughout Byzantine and Ottoman holdings, some more than others. Both Byzantine and later Ottoman sources write about these occurrences and the plague that persisted in Constantinople must have been partially why the city was half-deserted when Fatih Sultan Mehmed conquered it. As many people as possible had fled to nearby towns and castles not just to escape from the Turks in 1453 but also to avoid catching the plague.

Gisele Marien, in a Bilkent University thesis, attributes the sudden death of Yavuz Sultan Selim I to the plague in 1520. The description of the sultan’s physical symptoms suggests that possibility because the plague had broken out again seriously in Istanbul and Edirne and he was taken ill at a town in between the two cities. In this case, the sultan had been expected to be going on a military campaign but where other rulers were concerned, Marien, using a series of letters and diplomatic reports sent by the Venetians, speculates that the sultans and their entourages regularly retreated to towns or camped in meadow areas where the plague was not to be found.

Given the prevalence of plague throughout the Ottoman Empire and Europe most likely led to a situation in which those who survived were immune to the plague. Over time the knowledge of how the disease spread, the importance of cleanliness and the development of antibiotics have resulted in only very rare cases in the developed world.

The bubonic plague was apparently spread via commerce along the Silk Road and/or invading armies. The first known cases of bubonic plague occurred in the 1330s in China and spread to the Crimea by 1343. The year 1347 was a year in which Constantinople registered the plague and Genoese vessels brought the disease from there where merchants had been engaged in commerce. These traders docked in Messina, Sicily, in October of that year and were driven off by the townsfolk but not before they had spread the disease to land. By August 1348, the plague had reached England. In the Middle East, Alexandria in Egypt was first hit in 1347 and from there it spread east and north along the Mediterranean coast. It was reported in Mecca and Mosul in 1349.

The bubonic plague was apparently spread via commerce along the Silk Road and/or invading armies. The first known cases of bubonic plague occurred in the 1330s in China and spread to the Crimea by 1343. The year 1347 was a year in which Constantinople registered the plague and Genoese vessels brought the disease from there where merchants had been engaged in commerce. These traders docked in Messina, Sicily, in October of that year and were driven off by the townsfolk but not before they had spread the disease to land. By August 1348, the plague had reached England. In the Middle East, Alexandria in Egypt was first hit in 1347 and from there it spread east and north along the Mediterranean coast. It was reported in Mecca and Mosul in 1349. The plague and Istanbul

The plague and Istanbul