The Ottomans and their love of horses

Niki GAMM

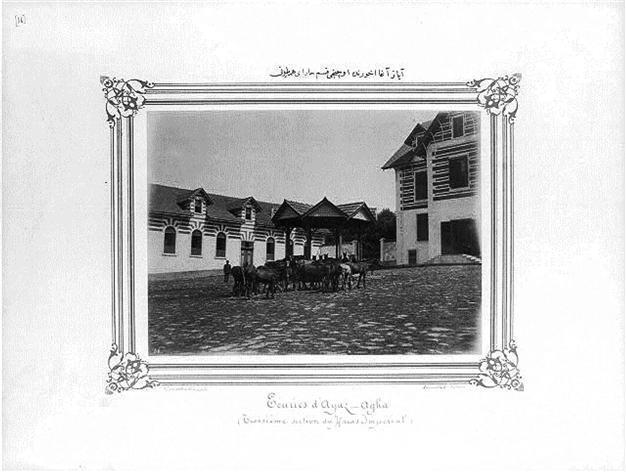

The imperial horses and stables at Ayazağa at the end of the 19th century.

The official entry of the president of Latvia, Andris Berzins, to Çankaya Palace in Ankara (April 16) was accompanied by a cavalry patrol and news reports pointed out that this was the first time that such an escort had been provided. At practically the same time, Topkapı Palace Museum hosted Saray Şenlikleri (Palace Festivities), which included equestrianism and archery on the palace grounds for the first time in 200 years. Modernization curtailed the use of the horse but it runs deep in Turkish history, especially among the Ottomans.The horse was the most important means of travel (and battle) among the Turkish tribes of Central Asia for millennia. They were bred for speed, strength, calmness and intelligence, among the attributes required at various times. These horses, known as Turkoman, are now considered extinct, but they undoubtedly left their genetic legacy behind. Their endurance was such that they were capable of sustaining a trot over many miles, a very useful gait for nomadic groups seeking new pastures and hunting for food, not to mention settling scores with enemies. In an article entitled “On the Foundation Turks,” author Jeremy James writes that the Kipchak Turks owned in excess of two million horses while the Uygurs had so many that only God knew the total.

The forefathers of the Ottomans entered Anatolia on horseback at roughly the same time as the Seljuk Turks began their conquest. The Battle of Manzikert in August 1071 in which the Turks overwhelmingly defeated a Byzantine army opened the way.

“The Ottoman Empire, was an exceedingly well-organized feudal military meritocracy. Everyone was part of the war machine. Land was granted to those considered worthy enough to hold it on behalf of the Sultan. These were known as timars. A timariot – a landholder – had usufructuary rights over the land and, as part of the deal, had to provide men and horses for the war machine. What is crucial to understand is that horses were not bred for money: they were bred because not only was it a state requirement, but it was also what an honourable man did and rivalry between timars ensured an ever spiralling quality of horseflesh. The timariot system could produce 200,000 mounted men on command riding highly schooled, big, beautifully bred horses without the Sultan putting a hand in his pocket,” James writes.

“The Ottoman Empire, was an exceedingly well-organized feudal military meritocracy. Everyone was part of the war machine. Land was granted to those considered worthy enough to hold it on behalf of the Sultan. These were known as timars. A timariot – a landholder – had usufructuary rights over the land and, as part of the deal, had to provide men and horses for the war machine. What is crucial to understand is that horses were not bred for money: they were bred because not only was it a state requirement, but it was also what an honourable man did and rivalry between timars ensured an ever spiralling quality of horseflesh. The timariot system could produce 200,000 mounted men on command riding highly schooled, big, beautifully bred horses without the Sultan putting a hand in his pocket,” James writes.The Ottoman army consisted of infantry and cavalrymen known as sipahi and the latter made up the majority of soldiers until the middle of the 18th century. In the 15th and 16th centuries it has been estimated that 40,000 or more could be raised each year, a figure that increased as the empire grew. The sipahis who were called up for service in the Balkans were taken from the European side of the empire while the sipahis of Anatolia would be expected to join the army on its eastern campaigns. The smallest timar supported one horseman who worked his own holding. Larger holdings had to supply horses and riders in proportion to their size.

Initially the sipahi was trained so he could accurately use a bow and arrow while in the saddle and that meant being able to turn and twist easily. In closer combat he would have used his sword, mace or a lance. In order to protect the horse, armor was developed that covered the horse’s face, neck and rump. The sipahi would also wear chain mail around the back of his helmet and covering his upper body. Of course none of this actually helped once firearms were introduced and used by the Ottomans and enemy forces opposing them.

A sizeable literature grew up on horsemanship and the medical treatment of horses. These were after all very valuable animals. These treatises included breeding methods, the training of the horse and horseman, hunting and ceremonial occasions. Tulay Artan in an article on one of these treatises from the reign of Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-1617) points out that Ottoman horse medicine relied on knowledge coming from the Greco-Roman period and augmented by Persian and Indian culture.

The sultan’s horses

Only the best horses would have been good enough for the sultan. In the early years of the empire, the sultan would have entered into combat himself but with time, he withdrew from the actual fighting to take up the role of observers. Later sultans didn’t even bother to go to battle but spent their time in ceremonial parades or hunting.

Elias Habesci who wrote his observations of the Ottoman Empire towards the end of the 18th century noted that the Ottoman sultan had 3,000 horses divided into three stables containing 1,800, 700 and 500 horses respectively. There were also 400 mules to transport any baggage the sultan and his suite might require when they left Topkapı to travel elsewhere. In addition to the sultan’s horses, all of the staff at the palace had horses and Habesci concludes that the imperial stables contained 6,000 horses in all. Even the lowest page would have three horses. The number of personnel working in the stables is given as 3,500. Unfortunately Habesci doesn’t give us any idea of where the stables must have actually been located because the stables that now exist at Topkapı Palace would have been hard put to house even 500 horses.

Once the imperial family decided to move up the Bosphorus, the stables had to move along with them. In the nineteenth century, these were located at Ayazağa.

Along with such valuable horses went valuable accoutrements such as velvet saddles with hand embroidery decorations in gilded thread. Wherever possible semi-precious and precious jewels decorated surfaces while stirrups might be gold plated. Some of these saddles, stirrups and reins are to be found in European museums as they fell into the hands of European knights and soldiers following some of the defeats of the Ottoman army such as happened after the second siege of Vienna.

Speaking of museums, the current Topkapı Palace Museum Director Prof. Dr. Haluk Dursun has announced that a new section of the museum will be opened devoted to horse culture and civilization.