The Jews and Anatolia: 2,500 years of history

NIKI GAMM

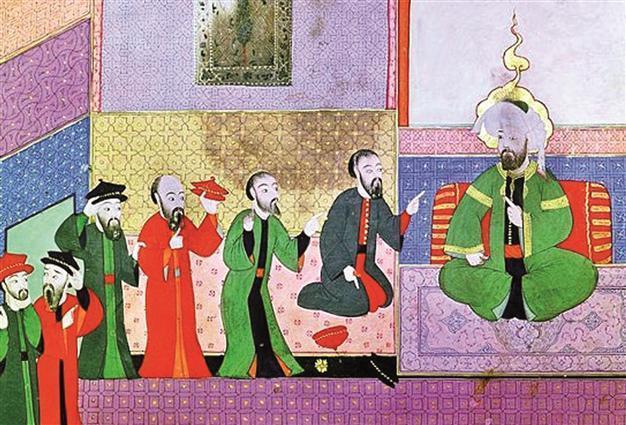

A Jewish delegation meets with an Ottoman official.

Centuries before the Turks arrived, Jews were living in Anatolia, likely encouraged by King Antiochus III (r. 223-187 B.C.) who had controlled the eastern Mediterranean. In 167 B.C., King Antiochus IV, who succeeded him, forbade Jews from practicing their religion but after a revolt by a provincial priestly family, the Maccabees, who conquered Jerusalem in December 164 B.C., the king promised that Jews living in his kingdom would not be harmed and would be permitted to follow their own customs. To this day the Jews celebrated this victory and call it Hanakkuh. This year, the holiday extends from Dec. 16 to 24.The earliest evidence for a Jewish presence in Anatolia, which has been dated to the fifth century B.C., even before the reign of Antiochus III, includes the remains of a synagogue in Sardis near the southwest coast of Anatolia. During the Roman period, they were protected in various provinces in spite of a rebellion and, while it is still a matter of historic research, they seemed to have fared pretty well during the Byzantine period. The main exception was that of Emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565) who attempted to assert his authority in religious matters in order to establish a single religion throughout his realm. By his various acts, he not only exacerbated differences amongst parts of the Christian church but “came into collision with the Jews, the pagans, and the heretics,” said A.A. Vasiliev, in his “History of the Byzantine Empire.”

“The Jews and their religious kinsmen, the Samaritans of Palestine, unable to be reconciled to the government prosecutions, rose in rebellion but were soon quelled by cruel violence. Many synagogues were destroyed, while in those that remained intact it was forbidden to read the Old Testament from the Hebrew text… The civil rights of the population were curtailed,” he said.

There were other occasional instances of the persecution of Jews in the period from the sixth century onwards. Byzantine authorities for the most part left the community alone. During the Fourth Crusade which resulted in the conquest of Constantinople in 1204, the Crusaders were particularly hostile toward Jews but seemed more interested in Jewish wealth and business activities than in converting the Jews to Christianity. After the re-conquest of Constantinople in 1261, the Byzantine authorities again developed a more tolerant point of view, but Jews were required to live in an area of their own rather than being allowed to mix with the general population.

Ambassador Claes Ralamb. 17th century.

As the Ottoman Turks began their rise to power in the 13th century, they would have had some contact with Jews. There were families living in Konya, Bursa and the Balkans and synagogues too. Bursa was the first major Ottoman capital from 1326 and later the Ottoman Turks established their capital in Edirne after conquering it in 1365. Even after the Ottoman capital moved to Istanbul, a large Jewish population remained in Edirne. Thirteen synagogues burned down in a fire there in 1907. Another very large synagogue was built to replace them and is currently undergoing restoration.

How many Jews were living in Constantinople at the time of the Ottoman conquest is unknown, but probably those who could afford to leave before the siege and capture had left. In order to encourage them to return, Mehmed the Conqueror had 100 poor families transferred from Kastoria in Greece’s Macedonia region. He also appointed the hahambaşı (chief rabbi) of Bursa to take charge of the Jewish community in Istanbul just as he had appointed a patriarch to look after the affairs of the Greek Orthodox Church. In his proclamation, the sultan told the Jews that God had commanded him to take care of the descendants of the Prophets Abraham and Jacob, to see that they had food to eat and to take them under his protection. They should come and settle in Istanbul and live in peace in the shade of the fig tree and vine where they could engage in free trade and own property.

The number of Jews in the Ottoman Empire increased significantly after the rulers of Spain expelled them, approximately 150,000, in 1492. While some fled elsewhere in Europe, many chose to come to Ottoman territory where they were welcomed by Sultan Bayezid II who was well aware of their value.

Stanford J. Shaw relates in his “History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey,” that “The Jews were allowed so much autonomy that their status improved markedly and large numbers of Jews emigrated to the Ottoman Empire from Spain at the time of the Christian reconquista and also from persecution in Poland, Austria and Bohemia, bringing with them mercantile and other skills as well as capital. They soon prospered and gained considerable favor and influence among the sultans of the later sixteenth century.”

The community was centered in Balat on the Golden Horn although it was spread out as far as Eminönü. At its height, it probably had about 50,000 members and 44 synagogues. The 17th-century travel writer Evliya Çelebi describes the work in which the Jews were engaged as including jewelry, medicine, textiles, cheese making, banking and taverns. Mehmed’s doctor for instance, Jacopo de Gaeta, was originally Jewish but converted to Islam, rising to the rank of paşa. The first printing house was established by two Jewish brothers in the Ottoman Empire in 1493. Joseph Nasi, who was originally from Portugal, achieved highly influential positions in the diplomatic area for Süleyman the Magnificent and his successor, Selim II, in the 16th century. He was even entitled Duke of Naxos and was instrumental in precipitating a war with Venice that ended with the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus.

There were certain restrictions, however, such as the kinds of clothing they could wear and not being able to bear weapons or serve in the military. After the Edict of Gülhane in 1839 was proclaimed, all the citizens of the empire were considered equal. The Jews of Turkey maintained an active public life, even though their influence gradually declined over the 19th century and into the 20th. Seven Jews were members of the first and second parliaments in 1877-78 and 1908, while there were eight in the Grand National Assembly of 1920. They even formed their own brigade to fight in World War I.