The history of the muezzin

Niki Gamm

If you live in a Muslim country, you hear the muezzin sounding the call to prayer five times a day. This is a tradition that extends back to the time of the Prophet Muhammad. The very first muezzin was a slave named Bilal ibn Rabah, the son of an Arab father and an Ethiopian mother (slave) who was born in Mecca in the late 6th century. Bilal was one of the earliest converts to Islam, but his owner tried to get him to renounce Islam by subjecting him to a series of torturous punishments. When his story became known, one of the Prophet’s followers, Abu Bakr, who later became the first caliph, bought him and set him free.

If you live in a Muslim country, you hear the muezzin sounding the call to prayer five times a day. This is a tradition that extends back to the time of the Prophet Muhammad. The very first muezzin was a slave named Bilal ibn Rabah, the son of an Arab father and an Ethiopian mother (slave) who was born in Mecca in the late 6th century. Bilal was one of the earliest converts to Islam, but his owner tried to get him to renounce Islam by subjecting him to a series of torturous punishments. When his story became known, one of the Prophet’s followers, Abu Bakr, who later became the first caliph, bought him and set him free.At about the same time, the number of people accepting Islam was growing. The number of prayers during a day seems initially to have been three, but later became five, but without clocks as we know them, the duty of praying together as a community was becoming difficult. One suggestion seen in a dream was to use a wooden clapper, a device found among the Christians; however, the man in the dream suggested the Muslims have someone vocalize the call to prayer (adhan in Arabic). This proposal found favor with the Prophet and he suggested Bilal, who was known for his beautiful voice. In the dream, the words to be recited were given as follows but here in English:

“God is most great! God is most great!

I testify that there is no god, but God.

I testify that Muhammad is the apostle of God.

Come to prayer! Come to prayer!

Come to salvation! Come to salvation!

God is most great! God is most great!

There is no god but God.”

Bilal went to Medina in 622 with the Prophet Muhammad and from then on served as his mace or spear bearer and steward on the various military expeditions that the latter undertook. As his steward, he was responsible for the whole treasury of the Muslims and distributed funds to widows, orphans and others in need. The Muslim forces captured Mecca and in January 630, Bilal climbed to the top of the Ka’aba to sound the call to prayer there for the first time. The sources are not clear about what happened to Bilal following the death of the Prophet in 632. One suggests that he continued to act as muezzin for the first Caliph Abu Bakr, but refused to do so for the second caliph. Another source notes that he only sounded the call to prayer twice more – once in Syria at the request of the second caliph, Omar and again in Medina because the Prophet’s grandsons asked him to do so. Bilal died at some time between 638 and 642 and was buried in Syria or in Jordan, depending on which source you believe. He is honored as the first muezzin by both Sunni and Shia Muslims.

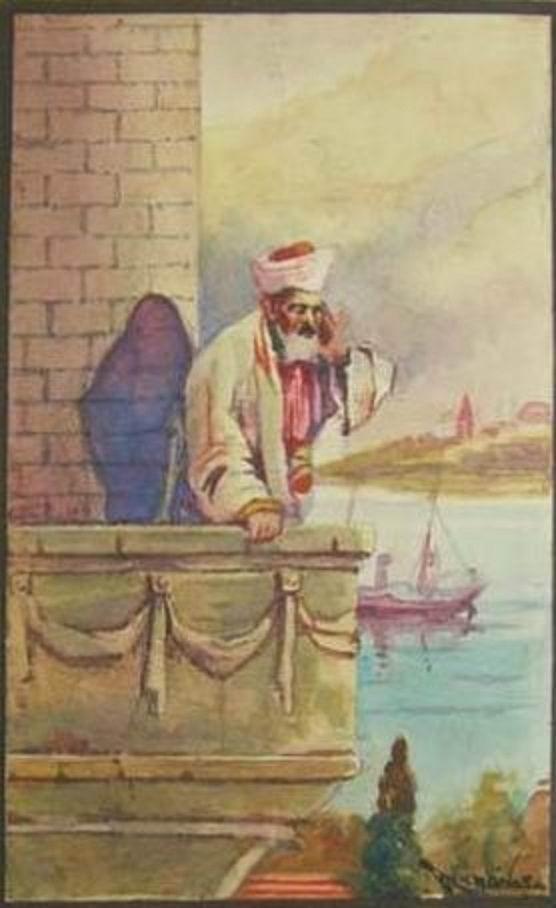

Muezzins take to the minarets

Muezzins take to the minaretsBilal started the tradition of sounding the call to prayer from a rooftop but, as Islam spread, the idea of building a tower for the muezzin appeared. The first minarets have been dated from 673, although they might have been built somewhat later. They come in various shapes and materials, such as brick or dressed stone depending on the local culture. The interior, though, had to be hollow in which a staircase for ascending and descending ensured that the muezzin could reach the balcony from which to give the call to prayer. The stone steps were high and narrow; worn down over time and they are difficult to climb, so it’s not surprising that using loud speakers from the ground has gained favor. Only a very few throughout the Muslim world have stairs on the outside.

Traditionally, mosques in the Ottoman Empire had only one minaret with the exceptions being the so-called imperial mosques. These were built in Edirne and Istanbul at the command of the sultan of the time. The four minarets at the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne are among the slimmest and highest ever built and have three balconies. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul has an unconventional six.

Muezzins during the Ottoman Empire

Muezzins among the Ottomans were among the personnel attached to mosques but were not required to hold an advanced degree from a madrasa (religious school), unlike those who actually led prayer services or delivered sermons. Basically, they were chosen for the quality of their voices. According to Gibb and Bowen in “Islamic Society and the West,” over the course of centuries, a series of modes were developed for the adhan and the muezzins were distinguished by whichever mode they used. In addition, they recited certain prayers that required responses from the congregation and at times performed functions at Friday prayers. In smaller mosques that had limited resources, they might also be employed to sweep the mosque and do other chores.

The imperial mosques might have as many as a dozen muezzins, as they would alternate the times when they would be on duty. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque had as many as 36 muezzins, in part because it became the leading mosque in the city and because it had six minarets. Their salaries came from the foundations that were set up to provide funds for each mosque.

The muezzins who served inside the palace were drawn from among the pages of the palace’s inner service who had particularly fine voices. They served under the Müezzin Başı (Chief of the Callers to Prayer), who not only supervised them, but officiated at whichever imperial mosque the sultan chose to attend for Friday prayer. He had a second in command (Seri Mahfil) who was in charge of “the private box behind the grille of which the Sultan followed the services in Imperial Mosques.” This latter person trained the pages who were being considered for the post of muezzin and made recommendations as to which one was suitable for the position. He was also responsible for the scheduling of the muezzins’ duties.

In the case of those promoted to muezzin in the palace service, Gibb and Bowen theorize that it, strictly speaking, meant the individual ceased to be a “slave” attached to the sultan and became a member of the learned class. The Müezzin Başı could go on to attain higher ranks including that of chief judge of Europe or Asia.