Homeless, traumatised and in some cases feeling abandoned by the authorities, many survivors of Morocco's powerful earthquake escaped death only to fear they are now on their own to stay alive.

The deadly quake has put a heavy burden on the North African kingdom's emergency resources and some stranded in shattered communities were angry and shocked over what they say is a lack of a major influx of aid.

"We feel abandoned here, no one has come to help us," said 43-year-old Khadija Aitlkyd among the ruins of her village of Missirat in a remote area high in the Atlas Mountains.

"Our houses have collapsed... where are we all going to live?" she asked in the rubble of the tiny, remote settlement where the smell of death hung in the air on Monday.

Residents of the village of under 100 people said bodies of the 16 locals killed in the quake have been recovered, but their dead livestock under the stones and timber was starting to decompose.

The violent shaking that flattened whole villages has inflicted a toll that rose on Monday to over 2,800 dead and almost as many injured.

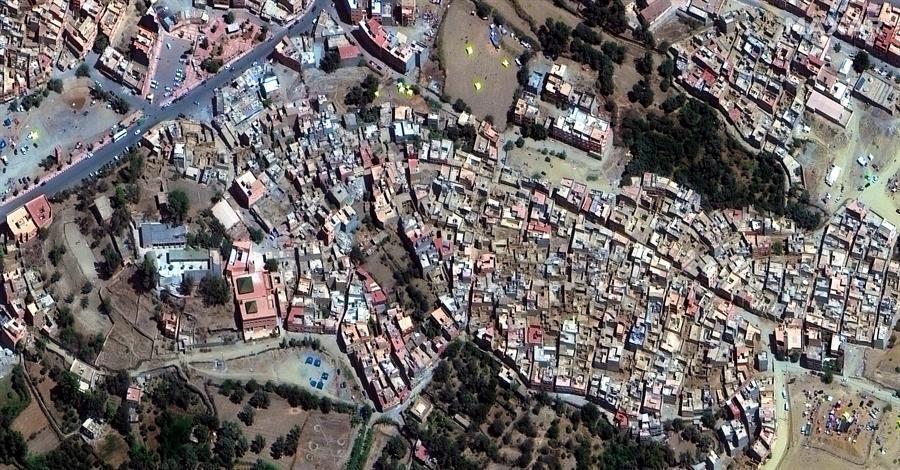

Another survivor, Mohammed Bouaziz, saw his village of Moulay Brahim south of Marrakesh hard hit in Morocco's deadliest quake in over six decades -- about 20 residents were killed.

"We have received some help... but it's not enough," said the 29-year-old who is part of a local group trying to meet the needs of over 600 residents left homeless.

With the help of local authorities and donors from the region, the group called Intikala has set up nine improvised camps crowded with women and children as men used their bare hands to clear rubble.

The most risk-taking among the men venture inside what remains of the structures in the village to salvage belongings at the core of daily life: mattresses, blankets and cooking utensils.

In the village of Missirat, which is about 300-kilometre (185 miles) drive southwest of Marrakesh, Mohamed Aitlkyd looked around and noted the absence of government aid workers or rescuers.

"The only time we saw the authorities was to count the number of victims in the hours after this disaster," said the 28-year-old. "Since then we haven't seen them once... nobody is here with us."

No government response was immediately forthcoming to the Missirat residents' complaints, but the Interior Ministry issued a statement Monday highlighting how the government was helping victims of the disaster.

"Authorities are proceeding with their efforts to rescue, evacuate and care for the injured and mobilise all necessary means," the ministry said.

Parallel to official efforts, privately organised aid convoys of food, water and blankets were a frequent sight on the twisting and narrow mountain roads near Missirat and clusters of other rural villages.

"We're here to give a hand to our brothers. We need to help these people," Yahia Mansour, a small trader, said from behind the wheel of a truck loaded with dozens of foam beds.

Yet in the face of such destruction in so many of the villages, which disintegrated under Friday's brutal shock, public and private aid efforts are likely to struggle to meet all needs.

More than 48 hours after the quake hit, running water was restored in Moulay Brahim and families were sharing the bathrooms of the few homes still standing.

As well as relishing these miniscule aspects of normality, survivors were grateful to be alive despite their current suffering.

Hasna Zahret, 39, said God gave her a second chance at life when neighbours rescued her from the rubble.

But the mother of three, whose husband is a day labourer making paltry wages, holds very little hope that her family will be sleeping indoors any time soon.

"Everyone is poor here," said Bouaziz, from the charity group Intikala.