Armed with a flask of coffee, some boiled eggs and a towel to shield his bare legs from the scorching sun, 90-year-old Frans Hugo sets off every Thursday to deliver newspapers in the South African desert.

Week in, week out, the elderly editor has made the 1,200-kilometer (750-mile) round trip across the semi-arid Karoo region in the country’s south.

He has been doing it for some four decades. Born Charl Francois Hugo in Cape Town in 1932 - but known to everyone simply as Frans - he is arguably the last bastion of a dying business. The energetic nonagenarian edits and hand-delivers three local papers, The Messenger, Die Noordwester and Die Oewernuus.

Driving an orange Fiat Multipla stacked with copies of the eight-page weeklies and with an old portable radio to keep him company, Hugo brings news to towns and villages dotting this vast, parched back-country.

He leaves at 1:30 a.m. from Calvinia, a small town of less than 3,000 souls about 500 kilometers north of Africa’s southernmost tip, and comes back in the early evening.

“I am like a pompdonkie,” he told AFP on a recent tour, using the local moniker for the nodding donkey pumps used to extract groundwater from boreholes. “I keep doing this every Thursday without fail. I will probably stop when I am physically not capable of doing it anymore.”

Hugo worked as a journalist in Cape Town and then in Namibia for almost 30 years before retiring to this remote region.

“I couldn’t handle the pressure anymore, so I moved to the Karoo,” he said. “Just as I was able to take a breath and relax, the man who owned the printers and the newspaper here in Calvinia came to ask me if I was interested in the business.”

His daughter and her husband got involved but tired and quit after a few months.

“I’ve been sitting with this thing ever since,” he quipped.

Cellphones and printers

Helped by his wife and three assistants, he has kept alive some historic small-town titles at a time where many printed newspapers around the world are struggling to survive the digital age.

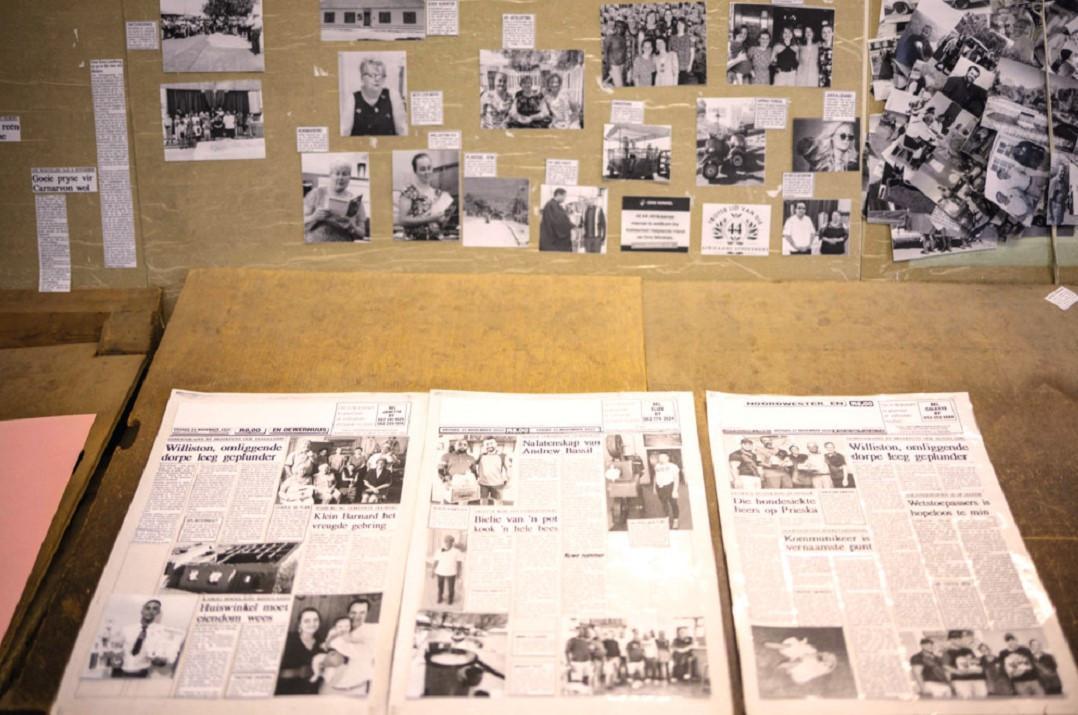

The Messenger, previously known as the Victoria West Messenger, was founded in 1875, while Die Noordwester and Die Oewernuus started printing in the 1900s. All three are written in Afrikaans, a language descended from Dutch settlers and one of South Africa’s 11 official tongues, but sometimes carry stories in English.

Hugo scoffs at people wanting “to read the news on their cellphones.” The rise of internet has hit readership but is seemingly yet to reach his newsroom, which looks like a museum. The office is adorned by an old Heidelberg printing press and paper cutting machines. Staff use computers and software from the early 90s.

Still, Hugo’s team prints about 1,300 copies a week, something he says shows an undying appetite for community news. The papers sell for eight rand (about 50 U.S. cents) and are dropped off at shops, convenience stores and the correspondents’ homes.

The readers are mainly farmers, living in a remote, semi-arid landscape.

Writing in Afrikaans, which actor Charlize Theron recently controversially said was still spoken only by “about 44 people”, keeps the language alive and ties together small communities separated by hundreds of kilometers of desert, said Hugo.

As long as he is around and has the required strength, they will receive their paper every Thursday. What will happen later does not concern him, he said. “I don’t have a clue what will happen... in five years or 10 years,” he said. “I am not worried.”