Republicans step back, House raises U.S. debt ceiling

WASHINGTON - The Associated Press

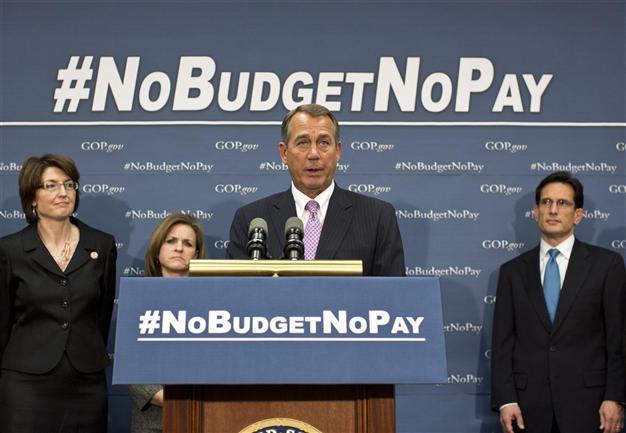

Speaker of the House John Boehner, R-Ohio, and the House GOP leadership have said that they will not agree to a long-term debt ceiling increase unless the Senate works with them to pass a budget deal and have also threatened to withhold Congress’s paychecks if either chamber fails to adopt a budget by April 15. AP photo

The U.S. House of Representatives approved legislation Wednesday to suspend for nearly four months the requirement for Congress to approve a higher limit on America’s borrowing, as Republicans who control the chamber backed away from an immediate battle with second-term President Barack Obama and a possible first-ever default on the country’s obligations.Until changing course, Republicans had been threatening to demand dollar-for-dollar spending cuts to match the increase in the nation’s borrowing limit.

At issue is the U.S. debt - nearly $16.5 trillion and rising fast. That’s the cumulative amount the country owes as a result of routinely spending more than it collects in taxes. The law requires that Congress approve raising the amount the government can borrow to pay its obligations - such as payments to contractors, unemployment benefits and interest payments to U.S. bondholders - as the debt exceeds the previous limit.

The House passed the measure by a 285-144 vote, a bipartisan showing on an initiative brought by majority Republicans. Harry Reid, the Democrat leader in the Senate, said the chamber would approve the action as well and send it quickly to President Barack Obama for his signature.

On Tuesday, the office of Management and Budget said the Obama administration would not oppose the short-term solution to the debt limit because the new Republican legislation "lifts the immediate threat of default and indicates that congressional Republicans have backed off an insistence on holding the nation’s economy hostage to extract drastic cuts."

Raising the debt ceiling once occurred largely as a matter of legislative course. But in 2011, a fight over the borrowing limit led to the first downgrading of the U.S. debt in the country’s history, despite a last-minute deal that saw both Obama and the Republican opposition give ground.

If the debt cap is not raised, the government would default on its obligations by as early as Feb. 15, the Treasury says.

With the debt ceiling issue back front and center in the partisan fight in Washington, Democrats criticize Republicans for using it as a tool to push their attempts to cut social programs and require a fight over the debt every few months.

Republicans had been threatening to use Congressional power over the federal budget to exact spending cuts from the Obama administration and Democrats that would equal the increase in the so-called debt ceiling. Republican budget cutters have long targeted the social safety net programs: Medicare health insurance for Americans 65 and older, Medicaid insurance payments that cover the poor, and Social Security, the federal pension for Americans of retirement age.

But the Republican leadership in the House decided to step back from an immediate confrontation by suspending the required approval of raising the debt limit until May 18, apparently deciding that Obama held the upper hand over congressional Republicans following his easy re-election to a second term in November.

The legislation does not set a specific debt limit. It would automatically increase the limit by the amount required to fund U.S. government obligations through that date.

Obama rejected threats

Even before his inauguration earlier this week, Obama rejected Republican threats not to approve raising the borrowing limit, saying he would not allow the opposition to "hold hostage" the "full faith and credit" of the United States. While he then voiced opposition to repeatedly having to deal with the issue, he apparently set that aside as the Republicans decided to suspend action for four months.

In his inaugural address on Monday, Obama was formidable in re-emphasizing his support for the key social programs that conservative Republicans want to cut dramatically.

While acknowledging the need to cut the deficit, Obama declared, "We reject the belief that America must choose between caring for the generation that built this country and investing in the generation that will build its future."

The House Republicans’ legislation was also designed to prod Senate Democrats to pass a budget after almost four years of failing to do so. It calls for withholding the pay of lawmakers in either the House or Senate if their chamber fails to pass a congressional budget resolution by April 15. House Republicans, who regained majority control of the chamber in 2010, have passed budgets for two consecutive years, but the Senate, which was in Democrat hands throughout Obama’s first term, hasn’t passed one since his first year in office.

Under Congress’ arcane budget procedures, a congressional budget resolution is a nonbinding measure that tries to set parameters for future legislation setting agency budgets and federal benefit programs like Medicare.

On Sunday, Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer said the Senate would do just that and would use it to call for follow-up legislation that would increase revenues. Most Republicans oppose higher taxes, contending that would only prove a drag on an already weak economic recovery. In the House especially, members of the Republican tea party faction won their place in Congress by promising constituents to shrink government and lower taxes.

Democrats have generally reacted coolly to the debt limit extension. They look also at other upcoming fiscal fights, including sharp, across-the-board spending cuts that would start to strike the Defense Department and domestic programs alike on March 1 and the possibility of a partial government shutdown with the expiration of a temporary budget measure on March 27.

While serious, those deadlines are far less consequential than defaulting on the country’s debt.