'Planetary emergency' due to Arctic melt, experts warn

NEW YORK- Agence France-Presse

AP Photo

Experts warned yesterday of a "planetary emergency" due to the unforeseen global consequences of Arctic ice melt, including methane gas released from permafrost regions currently under ice.

Columbia University and the environmental activist group Greenpeace held separate events to discuss US government data showing that the Arctic sea ice has shrunk to its smallest surface area since record-keeping began in 1979.

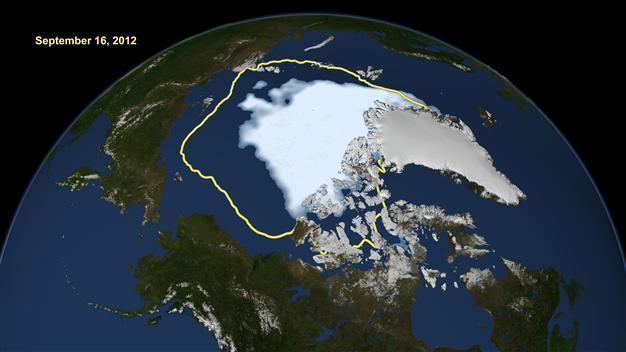

Satellite images show the Arctic ice cap melted to 1.32 million square miles (3.4 million square kilometers) as of September 16, the predicted lowest point for the year, according to data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado.

"Between 1979 and 2012, we have a decline of 13 percent per decade in the sea ice, accelerating from six percent between 1979 and 2000," said oceanographer Wieslaw Maslowski with the US Naval Postgraduate School, speaking at the Greenpeace event.

"If this trend continues we will not have sea ice by the end of this decade," said Maslowski.

While these figures are worse than the early estimates they come as no surprise to scientists, said NASA climate expert James Hansen, who also spoke at the Greenpeace event.

"We are in a planetary emergency," said Hansen, decrying "the gap between what is understood by scientific community and what is known by the public." Scientists say the earth's climate has been warming because carbon dioxide and other human-produced gases hinder the planet's reflection of the sun's heat back into space, creating a greenhouse effect.

Environmentalists warn that a string of recent extreme weather events around the globe, including deadly typhoons, devastating floods and severe droughts, show urgent action on emission cuts is needed.

The extreme weather include the drought and heat waves that struck the United States in the summer.

One consequence of the melt is the slow but continuous rise in the ocean level that threatens coastal areas.

Another result is the likely release of large amounts of methane -- a greenhouse gas -- trapped in the permafrost under Greenland's ice cap, the remains of the region's organic plant and animal life that were trapped in sediment and later covered by ice sheets in the last Ice Age.

Methane is 25 times more efficient at trapping solar heat than carbon dioxide, and the released gases could in turn add to global warming, which in turn would free up more locked-up carbon.

"The implications are enormous and also mysterious," said environmentalist Bill McKibben, co-founder of 350.org, a global non-governmental organization focused on solving the climate crisis.

For Peter Schlosser, an expert with the Earth Institute at Columbia University, the impact of the polar ice cap melt is hard to determine because "the Arctic is likely to respond rapidly and more severely than other part of the Earth.

"The effects of human induced global change are more and more visible and larger impacts are expected for the future," he said.

Natural resources, shipping lanes Some see the Arctic melt as a business opportunity -- a chance to reach the oil and gas riches under the seabed, and a path for ships to shorten the distance between ports and saving time and fuel.

According to the US Geological Survey, within the Arctic Circle there are some 90 million barrels of oil -- 13 percent of the planet's undiscovered oil reserves and 30 percent of its undiscovered natural gas.

The potential bounty that has encouraged energy groups like Royal Dutch Shell Co. to invest heavily in the region.

Greenpeace International head Kumi Naidoo says that oil companies have thwarted governments from taking action to cut back on greenhouse gas emissions.

"Why our governments don't take action? Because they have been captured by the same interests of the energy industry," Naidoo said.

Anne Siders, a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University's Center for Climate Change Law, warned against the "temptation" of sending ships through the area.

The new shipping lanes are dangerous to use because there are plenty of ice floes and little infrastructure for help in case of an accident -- which in turn increases the insurance costs.

Another consequence of global warming is that, as the oceans warm, more cold-water fish move north, "which means more fish will be taken out of their ecosystem," said Siders.

Caroline Cannon, a leader of the Inupiat community of Alaska, reminded the participants that her indigenous community, including her nine children and 25 grandchildren, depend on Arctic fishing and hunting for survival.

"My people rely on that ocean and we're seeing dramatic changes," said Cannon. "It's scary to think about our food supply."