Pandemic lockdown a chance to strengthen family ties

Barçın Yinanç - ISTANBUL

Alamy Photo

The COVID-19 pandemic stands to improve familial bonds with so many people in Turkey forced to stay at home, according to a leading psychologist and thinker.

“[The lockdown] is an opportunity to discover the language of the family and familial love,” Gündüz Vassaf told the Hürriyet Daily News this week.

“This is an opportunity for the concept of the family to consolidate and strengthen,” said Vassaf, who is currently in the United States.

Can you tell us what you see in the United States?

The state has collapsed and does not know what to do. U.S. society used to have high organizational skills, but since the polarization between the two parties these skills have been harmed. When the state’s organization collapsed, individuals did not know what to do. Gun sales have increased for instance in some states and [U.S. President Donald] Trump included guns on the list of essential goods.

Some suggest the pandemic will bring about the end of capitalism.

Some companies will go bankrupt; some new ones will flourish. We will save many companies with our taxes, just as was the case in past crises. Capitalism cannot survive without the state. The problem has been the fact that democracies – here I use it in the narrowest sense in terms of the legislative and judicial branches – did not inspect capitalism.

Currently, we are seeing the most extreme stage. Even though Trump had the authority, he did not want to touch the companies. Now it is too late; he is now calling on them to produce masks and ventilators.

How do you think Turkey is handling the pandemic?

Turkey is in between two worlds, in terms of how the West and the Far East approached the virus. There is a mosaic in the country. Some believe it’s God’s punishment; others are blaming the government. Some others are critical of the opposition because they object to everything. Some say we should do it like the Chinese; others compare it with America. There are lots of contradictory statements.

But then, ours is a society used to disasters. Turkish society has a lot of experience [with these sorts of things]. Without panicking, it has a type of mentality that says, “All of this will pass somehow.” We know what to do when the electricity is cut, and we know what it is like to have no running water – the West doesn’t.

It is more difficult for Turkish society to collapse compared to the West.

What do you think the short-term consequences of this pandemic will be?

We will be saved from industrialized art, from a culture of best-sellers and from Hollywood movies that are pumped up by billions of dollars’ worth of promotions. Thanks to the internet, so many new art forms have started to flourish. New forms of literature and music to appeal to those staying at home, especially children, have started to come out. They’ve been created via the internet but also at home.

As the days pass by, there are new discoveries in terms of what we can do at home; people are returning to shadow plays. There are so many things that are popping up from our cultural treasure chest. People are comparing what they do at home as if sharing their recipes. They find ways to live together without being dependent on something external. That’s extraordinary in terms of the dynamics of the family and society.

In addition, there are certain NGOs or civil initiatives that continue to work despite the outbreak, like those working to save the historic Yedikule vegetable gardens in Istanbul or those working to save the horses on the Prince’s Islands [near Istanbul in the Marmara Sea].

This is showing how strong civil society is, and this is tremendously important for the future. Because if the state collapses, we need to have civil society standing on its own feet. It is important that they do not give up on their activities because of the outbreak, because once this ends, their importance will be bigger.

If they were to collapse or postpone their activities on the grounds that we can take care of these issues later, years of labor will be wasted. We would have to start over. But currently, I see a lot of civil initiatives continuing in Turkey; this is great.

With the loss of power of the legislative and the increasing power of the executive, civil society has taken a lot on its shoulders. I believe Turkey is acquitting itself well in terms of civil society.

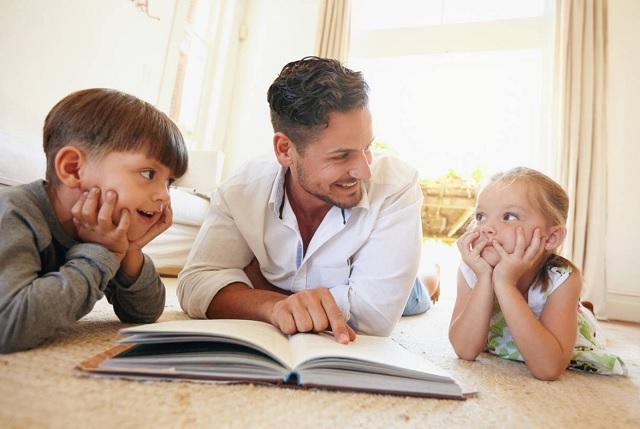

You said it’s important for family members to spend more time together; tell us why. Have family members become too disconnected?

In the neoliberal economy, parents left the house to make a living. In the past, one income was enough; now, there is need for two incomes. As a result, children have become lonely. Years ago, the head of the World Health Organization asked delegates about the biggest threat to global health, and his answer was the end to the family meal. Indeed, we see each other at that family table; we know each other, and even if one doesn’t directly relate a problem, we sense it. And the menu on family tables is better than junk food.

For the first time, parents are [now] spending many hours together; this is a challenge for families. This is a test for couples, especially men. In the past, we came across instances when retired men had problems adapting to household life. So this is going to be a test for marriages, as well as a test for parenting. Parents are not used to being together so long with their children.

But this is an opportunity as much as it is a challenge; it’s an opportunity to discover the language of the family and familial love. Love is not limited to saying “I love you,” but love expressed in the form of playing together and listening to each other without interrupting since there is time now. This is an opportunity for the concept of the family to consolidate and strengthen. The continuation of the unity of family is important, especially at a time when the state order is being harmed.

Families are the smallest civil society institutions. If we come out [of this ordeal] with NGOs and families collapsing, people at each other throats … individuals atomized and us unable to rewrite family history, this will offer an invitation to totalitarian order. There is a lot of responsibility on our shoulders, but this also entails pleasant times.

We are not talking about a mine worker working in the depths of a mine. We are talking about a process that will create love and encourage creativity.

Any final words?

I have strong criticisms for the media. This is an unknown disease, and information about it keeps changing. The continuous debates lead to passivity, which then leads to depression, and depression ruins our immune system. The media should act in a more sensitive way. Giving information about the disease three times a day should be enough; it should then give more coverage to other issues like culture. This is not the case.

And there are also other dimensions to the outbreak, like refugees. God knows what happens on that front. The media’s role is to focus and shed light.

Finally, we are currently interested in news in a pathological way. Yet even in concentration camps, there were times during the day when people sang and danced in spite of everything. Laughing, having fun, making love – these things aren’t shameful. We are not talking about fun with reckless abandon, but having fun is important to stay healthy and protect ourselves. We should not criticize others for sharing jokes or dancing at home – quite the contrary.

Corona is not writing history; we are writing it. The reaction we give to the outbreak is writing history

Who is Gündüz Vassaf?

Gündüz Vassaf is a writer and psychologist. Vassaf first worked as a clinical psychologist before taking a teaching position at Boğaziçi University. As a result of the military coup of 1980, he became a visiting professor at universities in Germany.

Vassaf was a member of the Board of Directors of the International Council of Psychologists, as well as the regional coordinator for Europe and the Middle East for the American Psychological Association’s Division of Community Psychology. Vassaf was also a founding member of the Committee for Peace of the International Union of Psychological Science and the Turkish Psychological Association. Furthermore, he helped found the Istanbul Amnesty International branch.

Vassaf has published 16 books in Turkish, and some of his books have been translated into five languages, including “Prisoners of Ourselves: Totalitarianism in Everyday Life.” His writing focuses on the psychology of everyday life, especially the quest for freedom. At present, Vassaf is working on a novel about Caravaggio.