Oscar-winner Zsigmond dies before Atatürk dream comes true

Fuad Kavur - LONDON

On a cold November night, in 1956, two young students of cinematography got on a train from Budapest, bound for the Austrian border. They were carrying with them four cans of 35-millimeter film – their dowry for their escape to the West.

On a cold November night, in 1956, two young students of cinematography got on a train from Budapest, bound for the Austrian border. They were carrying with them four cans of 35-millimeter film – their dowry for their escape to the West. The students were Laszlo Kovacs and Vilmos Zsigmond. The cans of film they had with them contained what they secretly had been filming, Soviet tanks that Nikita Khrushchev had dispatched to brutally crush the Hungarian Uprising – the few weeks of freedom Hungarians tasted as they liberated themselves from the communist régime that had hitherto ruled Hungary as a Soviet satellite.

By the time it approached the Austrian frontier, Kovacs and Zsigmond were the only passengers left on the freezing train. Finally, the driver announced he was not prepared to go any further, as the frontier was awash with Soviet troops. So, the two youngsters jumped off and started their walk toward Austria. It was cold and pitch-dark, and the two – carrying highly incriminating footage with them – were frightened.

Sure enough, within minutes, they could see a Russian army vehicle advancing toward them in the distance. Vilmos said to Laszlo, “For heaven’s sake, let’s get rid of the film.”

Laszlo would hear none of it. The grand scheme was to make their way from Vienna to America, from which they would sell the footage to one of the main TV stations, ABC, NBC or CBS. At the moment, however, they could clearly see the Soviet vehicle approaching toward them.

Vilmos told Laszlo that they would surely be shot on the spot if they were apprehended with the cans of film. Laszlo finally caved in – on condition that they quickly bury the cans so that they could return later and dig them out. As they finished burying the cans, the Soviet militia caught up with them. They asked what Vilmos and Laszlo were up to so late at night. They replied that they lived in a nearby village. Of course, the militia knew they were lying. Still, they merely took all their money, as well as their wristwatches, before letting them go.

After that, all Vilmos wanted was to head for the Austrian frontier. However, Laszlo would hear none of it; they had to find the buried cans – in the pitch-black and in the woods! It was like looking for a needle in a haystack. However, as the day was breaking, they managed to locate the cans. Finally, in the morning, exhausted and penniless, they were in Vienna.

Having spent some time in the Austrian capital, trying to obtain travel documents and funding, Vilmos and Laszlo finally made it to New York – with the cans of film. By then, however, no American TV station was interested; it was “yesterday’s news.”

Vilmos told me this story a few years ago over dinner at the famous Gundel restaurant in Budapest. Although by then an Oscar-winning cinematographer, he said he had never forgotten that fateful night. That revealed to me something about Vilmos – fame and success had not changed him.

That is why when I asked him during the Gezi Park protests whether he would become a signatory to the open letter addressed to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan that would be published as a full-page ad in The Times, he did not hesitate to oblige. Having seen the Hungarian Uprising so brutally crushed, Vilmos told me that he knew what tyranny meant.

Vilmos won an Oscar as a cinematographer and received a nomination for another one. He won countless other awards – including a Life Time Achievement Award at the Cannes Film Festival in 2014.

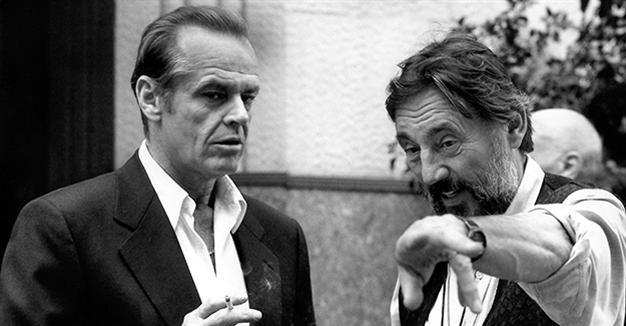

Working with the greatest Hollywood directors, such as Steven Spielberg, Michael Cimino, Robert Altman, Brian de Palma and Woody Allen, the cinematographer filmed some of the most memorable movies in the world, such as “Close Encounter of the Third Kind,” “The Deer Hunter,” Witches of Eastwick,” “Blow Out,” “Sugarland Express,” “Bonfire of the Vanities,” “Heaven’s Gate” and “Melinda & Melinda” – films starring luminaries such as Robert de Niro, Jodie Foster, Jack Nicholson, Michelle Pfeiffer, Mel Gibson, Warren Beatty, Julie Christie, Richard Dreyfus and Scarlett Johansson, to name but a few.

Last but not least, his greatest dream was to make a film about modern Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Living on the West Coast, he flew to Hungary countless times to choose locations with me and our producer, Anthony Waye. Vilmos loved Atatürk, an epic, which he hoped, would be his swan song.

Fate determined otherwise. This is something that I will regret forever. Still, Atatürk is his film and will be dedicated to him.

So long, Vilmos.