Aligning for 2019 elections

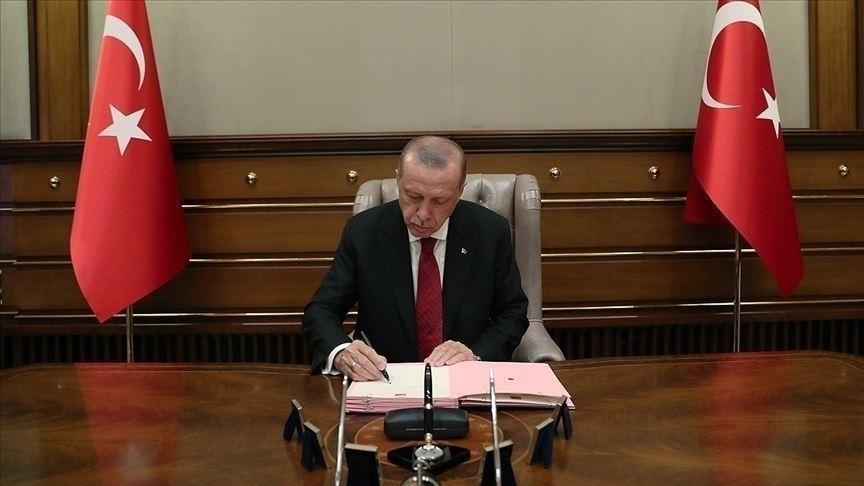

After a suggestion by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey has started discussing an issue that might have serious impacts on the entire political system of the country. In many countries, parties, political groups or independents form alliances for elections to boost their chances in parliamentary or presidential elections. Can Turkey walk the same road? What could the consequences of such an alignment be?

Can Turkey undertake a constitutional amendment for an electoral law regulation allowing political parties to enter elections under an umbrella party? If that can be done, could it be applied for local elections next year or parliamentary and presidential elections in 2019?

Perhaps the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) is clever enough not to walk such a road that might be detrimental for its future. Recent public opinion polls show that after the establishment of the Good Party (İyi Parti) there has been a radical decline in the popularity of the MHP. According to the polls, the party could stay well below the current 10 percent electoral threshold. A party getting 6 to 8 percent of the national vote could of course prefer to get into an alliance in order to enter parliament by placing its candidates under a bigger party. Could that be the case? Probably.

Although MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli has been asserting that his party has no worries about not being able to pass the threshold, and that all its critics would see the great success it would achieve in the next elections, rumors are rampant that efforts of an alliance are already underway. Could the MHP actually form an alliance with the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) as speculated?

Lowering the electoral threshold to 5 percent might help the MHP, but could produce some other complications for the MHP and Erdoğan’s aspirations to secure an easy election victory. With a 5 percent threshold, the Kurdish vote might remain with the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) even though most of its deputies have been imprisoned or subjected to serious prosecution. With a five percent threshold, the Kurds might have two important reasons to shun the AKP and deny it their precious support.

The talk of the town is that the MHP would get one or two vice presidency roles and a contingency of minimum 40 “electable” places on the AKP’s parliamentary candidates’ lists in the 2019 elections. Though it sounds rather realistic and probable, walking such a road might bring the end of the MHP all together. In the absence of the MHP in the parliamentary race, the Good Party might find an opportunity to consolidate itself far easier. On the other hand, if the MHP enters the race alone and gets as anticipated below 10 percent in the absence of a regulation to lower the threshold to five percent or less in the national vote, not only the MHP might face an existential threat, the AKP might lose a political crutch that it very much would need in the post-2019 period even if Erdoğan is elected president.

It is becoming rather clear nowadays - after the establishment of the Good Party – that there has been a vacuum in the center right of the Turkish political spectrum from which the AKP benefitted since 2007. Now there is a center-right party; and it is eroding not only the MHP but also the AKP and to some extent the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP). More interestingly, the new party seems like it could get some serious support from the Kurdish population of southeastern Turkey as well.

Can Turkey come out of its current predicament and enter a democratic atmosphere? It might not be that easy.