‘The hollowing of Western democracy’

William ARMSTRONG - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy’ by Peter Mair (Verso, £15, 160 pages)

‘Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy’ by Peter Mair (Verso, £15, 160 pages)  A popular narrative about present day Turkey is that its current government is steadily monopolizing all levers of power and extending its authority into every state and private institution - an authoritarian power grab justified with rhetoric about the “popular will.” Read in Istanbul at the moment, the argument of the late Peter Mair’s “Ruling the Void” thus seems rather counterintuitive. Mair warns of how Western democracies’ denigration of the “popular” component of democracy has contributed to the decline of traditional mass parties in recent decades, and has gone hand in hand with the emptying out of ideology. With authority increasingly being delegated to a series of essentially unaccountable international institutions, the result is a “self-generating momentum whereby the parties become steadily weaker and democracy becomes even more stripped down.” Mair died suddenly at the age of 60 in his native Ireland, leaving this book unfinished, but sensitive editing from existing notes and other published pieces has resulted in an unsettling and convincing volume. It makes for a bracing read not only in today’s Turkey, but also in the aftermath of the “populist surge” in the recent European Parliament elections.

A popular narrative about present day Turkey is that its current government is steadily monopolizing all levers of power and extending its authority into every state and private institution - an authoritarian power grab justified with rhetoric about the “popular will.” Read in Istanbul at the moment, the argument of the late Peter Mair’s “Ruling the Void” thus seems rather counterintuitive. Mair warns of how Western democracies’ denigration of the “popular” component of democracy has contributed to the decline of traditional mass parties in recent decades, and has gone hand in hand with the emptying out of ideology. With authority increasingly being delegated to a series of essentially unaccountable international institutions, the result is a “self-generating momentum whereby the parties become steadily weaker and democracy becomes even more stripped down.” Mair died suddenly at the age of 60 in his native Ireland, leaving this book unfinished, but sensitive editing from existing notes and other published pieces has resulted in an unsettling and convincing volume. It makes for a bracing read not only in today’s Turkey, but also in the aftermath of the “populist surge” in the recent European Parliament elections. Mair spends much of the first part tracing the erosion of the conditions that previously sustained mass parties, backing up his argument with plenty of meaty diagrams and empirical data. “Electoral identification with political parties is now almost universally in decline, and the sense of attachment to party has been substantially eroded,” he writes, putting this down – among other things – to the disintegration of the wider collective networks that previously sustained parties:

As workers’ parties, or as religious parties, the mass organizations in Europe rarely stood on their own, but constituted just the core element within a wider and more complex organizational network of trade unions, churches, and so on ... With the increasing individualization of society, traditional collective identities and organizational affiliations count for less, including those that once formed part of party-centered networks.

Given the absence of coherent and relatively enduring social constituencies, there is little remaining on which parties can build or identify stable alignments, and without the institutional and social ties binding them together the gap between voters and parties widens inexorably. In these circumstances the “left-right divide loses its interpretative meaning” and “it is almost impossible to imagine party government functioning effectively or maintaining full legitimacy.” The twin processes of popular and elite withdrawal from mass electoral politics are leading to the hollowing out of democracies and the emergence of a governing class bereft of legitimacy.

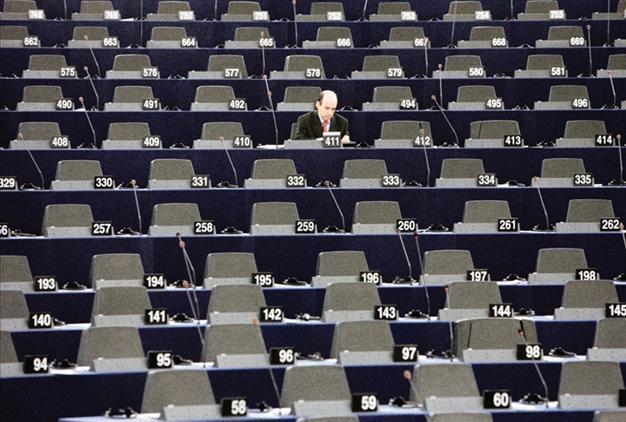

Though unfinished, the book could perhaps spend more time considering the structural economic forces that have also been driving the wedge between citizens and decision-making. If it were written today, the colossal mess of the euro crisis would be a good place to start – with voters’ preferences in debtor countries seen as little more than irritating obstacles for the technocratic European authorities to overcome. In the second part, Mair turns his attention to the European Union, to explain how depoliticization and disengagement have gone hand in hand with the deepening of European integration. Looked at from the outside, the EU can sometimes look like a kind of democratic utopia, but in Mair’s account it exemplifies the extent to which ordinary citizens are now alienated from the decision-making processes that shape their lives. Despite the seeming availability of channels of access, the scope for meaningful input and hence for effective electoral accountability is very limited, “the behavior and preferences of citizens constitute virtually no formal constraint on, or mandate for, the relevant policy-makers.” This is not accidental, but symptomatic of the desire to keep policy-formulation safe from the demands of voters and their representatives, a desire based in the growing sense that the mechanisms of popular democracy are increasingly incompatible with the needs of policy makers. “What governments appear to need by way of policies is not necessarily what voters will accept,” Mair writes, “and what makes for a successful strategy in the electoral arena may not offer the best set of options for government policy.” By shifting decision-making one level higher, he adds darkly, “the architects of the European construction have been able to leave democratic procedures behind.”

As I read “Ruling the Void” I kept returning to the economist Dani Rodrik’s idea of the inescapable “trilemma” of globalization, which says democracy, national sovereignty and global economic integration are mutually incompatible: Any two of the three can be combined, but we can’t have all three simultaneously and in full. A populist backlash to this whole situation is warned about throughout Mair’s book, and the breakthrough of anti-establishment forces in the recent European Parliament elections make it particularly apposite today. I expect that Mair would have argued that this populist surge - and the extraordinary cynicism of so many European citizens toward the political process today - is not purely the result of EU expansion, but a result of the entire process of depoliticization, of which the EU is only a part.

As I mentioned at the start, the book makes for quite a strange read in Turkey, where “popular democracy” slips further into destabilizing demagoguery by the day. It also suggests another way to consider the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) troubled relations with the EU: Is it really surprising that a tub-thumping, muscle-flexing, populist government backed by considerable public support is clashing so openly with the bloodless, technocratic, coldly insolent institutions of the EU? Limp as it sounds, one can only hope that both can find a better balance between the popular and constitutional forms of democracy.