'Reckless' by Hasan Ali Toptaş

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Reckless’ by Hasan Ali Toptaş (Bloomsbury, $30, 336 pages)

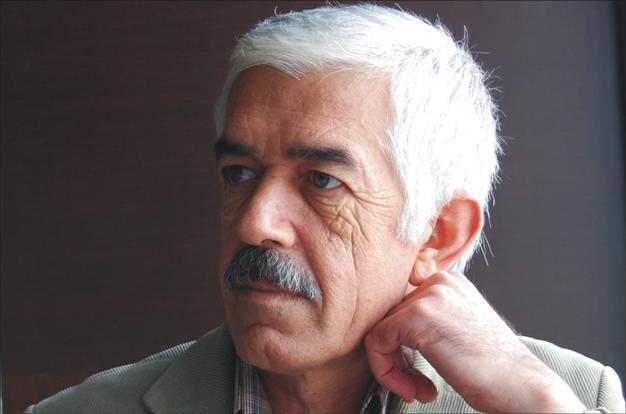

‘Reckless’ by Hasan Ali Toptaş (Bloomsbury, $30, 336 pages)Hasan Ali Toptaş is one of Turkey’s most well-regarded contemporary authors. He has been translated into German, French, Dutch, Swedish and Korean, but his 10th novel “Reckless” is the first to appear in English. It is a curate’s egg - sometimes excellent, sometimes clumsy.

Wearyingly, his publishers describe Toptaş as “Turkey’s Kafka.” By this they mean that he is a weaver of dark, sometimes surreal tales, in which the border between reality and imagination is artfully blurred. In the dense first third of “Reckless” memory, fantasy and real life are blended in a kind of extended dream sequence. In another author’s hands, this could have been handled more convincingly. As it is, plenty of readers will be exasperated and many will give up within 100 pages.

At the start of the book we are introduced to Ziya, returning the key of his 19th floor apartment to his landlady before leaving one of Turkey’s sprawling metropolises. What follows is an often confusing cavalcade of recollection and hallucination, as the landlady describes her past and how she came to own the apartment building. Fragments of Ziya’s own childhood pop up - haunting episodes that have marked his entire life. The narrative is intentionally disjointed, full of extraneous phrases and portentous dialogue leading down cul-de-sacs.

At the start of the book we are introduced to Ziya, returning the key of his 19th floor apartment to his landlady before leaving one of Turkey’s sprawling metropolises. What follows is an often confusing cavalcade of recollection and hallucination, as the landlady describes her past and how she came to own the apartment building. Fragments of Ziya’s own childhood pop up - haunting episodes that have marked his entire life. The narrative is intentionally disjointed, full of extraneous phrases and portentous dialogue leading down cul-de-sacs. But the pace eventually picks up. Many of the motifs introduced in the labored opening third are developed after Ziya retreats to the remote village of his old friend Kenan, who he met during military service 30 years before. Their fates seem to be twinned: After military service together in the same post at the same dates, both lost their wives, and neither remarried or had children. Ziya has gone to the village “tired of dealing with life’s chaos,” hoping for “a simple life, where one plus one equals two.” He remains traumatized by the death of his wife and son in a terrorist bombing 16 years ago. He is also unable to shake the memory of killing an innocent bird as a young boy - a silhouette “always there, just beyond my lashes … like an electric current sending one image after another.”

In the central section of the novel, Ziya and Kenan’s grueling two years of military life in Turkey’s southeast are described in ruthless detail. Toptaş abandons the ponderous earnestness and switches to a more immediate, vivid narration of the horrors experienced during their posting on the treacherous Syrian border, surrounded by sadistic commanders, casual savagery, suicide, rheumatism, lice, mosquitos, and stale bread. The book remains almost entirely free of contextual details, leaving the reader to estimate when exactly the action is set. Tension is more important for what it does to characters’ psychology than for any political import.

On the whole, “Reckless” is full of unpursued threads that are left hanging inelegantly. The dialogue makes many of the characters sound barely distinguishable from each other, and Ziya himself is a frustratingly blank figure, shrugging his way through 300 pages and taking few initiatives of his own. Translators Maureen Freely and John Angliss have a difficult balancing act, as it is not their job to polish Toptaş’s cruder edges. There is little they can do with his penchant for ripe metaphors; at one point we are told that “the silence, it could turn a man to stone.”

Nevertheless, by the time we reach the novel’s impressive final set piece in the village, the tiring slog of the first third - as traumatic for the reader as Ziya’s brutal military service - is a distant memory. The closing scenes end up packing quite a punch and linger long in the memory. The publisher Bloomsbury is next year planning to release Toptaş’s “Gölgesizler” (Shadowless), his most lauded work in Turkish. On the strength of “Reckless,” English readers should be cautiously looking forward to it.