No road to paradise

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

Painted houses in Beirut's southern Ouzai neighborhood. AFP photo

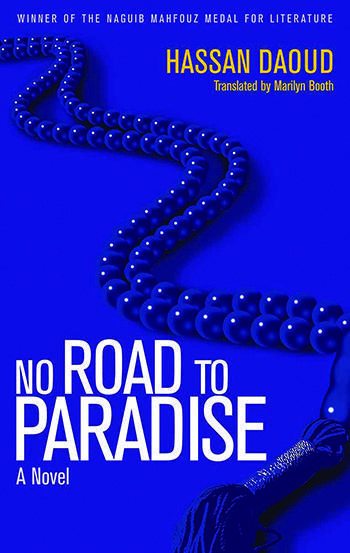

‘No Road to Paradise’ by Hassan Daoud, translated by Marilyn Booth (AUC Press/Hoopoe, 304 pages, $18)In “No Road to Paradise,” novelist Hassan Daoud describes the life of a disillusioned imam in a Lebanese village after he is diagnosed with cancer. Daoud’s ninth novel, it won the prestigious Naguib Mahfouz Prize for Arabic Literature in 2015 and this new English translation was highly anticipated. Sadly it leaves the reader rather cold and unmoved.

The imam spends most of his time looking after his aging and infirm father who cannot speak. He has children who are deaf and he is married to a woman who is coldly contemptuous of him. He lusts privately after the widow of his late brother but he is beset by a slow, degenerative disease. Gradually losing interest in his religious life, he remains passive in the face of a threatening new fundamentalist group that appears in his mosque.

A grey haze hangs over the imam, preventing meaningful or fulfilling engagement in anything around him. “I felt sometimes as though I were in a permanent and losing struggle,” he observes at one point. “There was no one – not in Shqifiyeh and nowhere else either – to whom I could talk as I so badly wanted to talk. I was alone among them.”

“No Road to Paradise” has been praised for its minimalist narrative voice, prioritizing psychological truth over plot. One of the Mahfouz Prize judges praised its “slow, meticulous, stagnant narration.” Stagnant is a strangely appropriate word to use. Rather than meditative, the novel is needlessly ponderous; at one point the narrator takes three pages to describe recovering from a general anesthetic. Perhaps the intention is to uncover riches in overlooked quotidian details, like Flaubert or Chekhov, but in Daoud’s hands the literary rationale is rarely apparent.

Compounding this problem is clumsy phrasing. Daoud often uses five words when three would do. Here’s an example: “In any case, her appearance had undergone some slight alteration since the moment shortly before when she had turned to go into the kitchen.” Surely this would be more effective as: “Her appearance had changed slightly since she had gone into the kitchen.” In the same paragraph, we read: “she had patted into place what could be seen of her hair beneath her head covering.” Surely this would be better as: “She had fixed her hair beneath her head covering.”

Whether it is the fault of Daoud or translator Marilyn Booth, the cumulative effect of needlessly detailed descriptions is exhausting. They also jar with the spartan nature of the plot. Ultimately, “No Road to Paradise” aims to capture the frustrations and false starts of an ordinary life. Sadly it has none of the power of Chekhov or Ibsen.

Daoud has

spoken eloquently about the fact that Western readers do not want Arab literature to deal with the same topics as they would expect from their own authors. Either they want some reference to the “exoticism” of the Arab world or sweeping insights about the culture where the work is set.

“No Road to Paradise” is certainly rooted in place, but it makes no explicit social or political points that would satisfy most English readers. The greater disappointment is that its labored narration delivers so little after promising so much.

* Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via iTunes here, Stitcher here, Podbean here, or Facebook here, or Twitter here.

The imam spends most of his time looking after his aging and infirm father who cannot speak. He has children who are deaf and he is married to a woman who is coldly contemptuous of him. He lusts privately after the widow of his late brother but he is beset by a slow, degenerative disease. Gradually losing interest in his religious life, he remains passive in the face of a threatening new fundamentalist group that appears in his mosque.

The imam spends most of his time looking after his aging and infirm father who cannot speak. He has children who are deaf and he is married to a woman who is coldly contemptuous of him. He lusts privately after the widow of his late brother but he is beset by a slow, degenerative disease. Gradually losing interest in his religious life, he remains passive in the face of a threatening new fundamentalist group that appears in his mosque.