Juan Goytisolo’s essays from the Muslim Mediterranean

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Cinema Eden: Essays from the Muslim Mediterranean’ by Juan Goytisolo (trans. Peter Bush) (Eland, 2003, 25TL, pp 144)

‘Cinema Eden: Essays from the Muslim Mediterranean’ by Juan Goytisolo (trans. Peter Bush) (Eland, 2003, 25TL, pp 144)

Mid-way through this slim book of essays “from the Muslim Mediterranean,” Juan Goytisolo gives a semi-fictional account of meeting a hermit in Cappadocia, who tells him an unlikely tale of how Antoni Gaudi fled to Central Anatolia before his death. The Cappadocian landscape bears striking aesthetic resemblances to Gaudi’s Barcelona, while fellow-Catalan Goytisolo’s flight also turns out to have similarities to Gaudi’s imagined journey. Reflecting on what the two of them share, Goytisolo writes: “There could be nothing more natural for [Gaudi] than to disappear from that mediocre, positivistic world which was stifling him … Europe could no longer bring anything to him: that is why he came here.” Egotistical it may be, but the passage is more successful than most of what surrounds it, with the author at last finding a moderately interesting form for his tired concept of bourgeois flight. Unfortunately, for all its pretense of metropolitan sophistication, the rest of the book mostly deals in broad, reductive brush strokes.

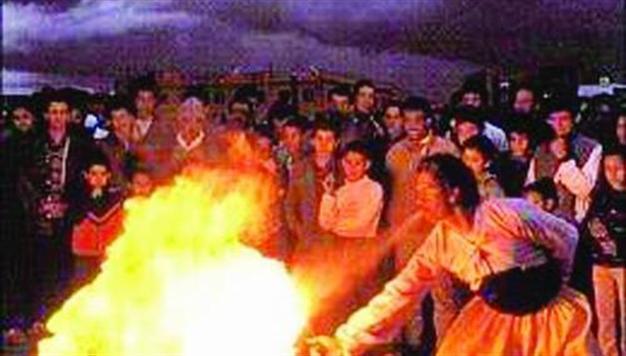

The flight from hidebound Western utilitarianism to the unorthodox and dangerous is a well-trodden path, but over time it has become an extremely trite conceit. So it may come as a surprise to discover a celebrated modern Spanish writer still doggedly plowing the tired anti-bourgeoisist furrow. Goytisolo has lived in a self-imposed (or self-admiring) exile from his home country since 1956 - and in Marrakech since 1997 - from where he has written poetry, novels, political essays, and travel narratives. The glue holding together his ruminations on Morocco, Turkey, and Egypt is that slightly tiresome disdain for “bourgeois ordinariness.” All three countries, in different ways, strike against such perceived mediocrity.

Unfortunately, in expounding this theme, most of “Cinema Eden” ends up not only being rather humorless, but also astonishingly unsubtle. Barely a word of ambiguity infects Goytisolo’s wholehearted embrace of “the East” as a panacea to all the maladies of the crudely materialist West. That is little more than a form of lofty condescension, as if Goytisolo sees these places as not being sophisticated enough for a deeper investigation. However sincerely one may “love the East,” to do so almost purely on the basis of its opposition to “cruel, unbridled modernity” is to be guilty of a kind of reverse Orientalism. However justified his skewering of Western complacency may be, there’s something immensely patronizing about a European finding its solution in an “East” defined by its opposition to modernity. Like a marginally higher-brow "Eat Pray Love," he’s actually holding the East in just as much contempt as the West.

The essays collected here also contain purple prose truly worthy of pseuds corner. In the "palimpsest city" (yawn) of Istanbul, for example, we’re told not only of the “splendor of its monuments,” but also of its “semiotic richness, its subtle interplay of synchrony and diachrony.” After trudging through pages of such ripe obfuscation, barely masking crude oversimplifications, it was a relief to finally close the book.

Recommended recent release

'Shadows of Anzac: An Intimate History of Gallipoli' by David Cameron

(Big Sky Publishing, 15TL, Kindle edition pp 414)

William Armstrong,

‘Cinema Eden: Essays from the Muslim Mediterranean’ by Juan Goytisolo (trans. Peter Bush) (Eland, 2003, 25TL, pp 144)

‘Cinema Eden: Essays from the Muslim Mediterranean’ by Juan Goytisolo (trans. Peter Bush) (Eland, 2003, 25TL, pp 144)