İzmir, 1840-1880

William ARMSTRONG - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

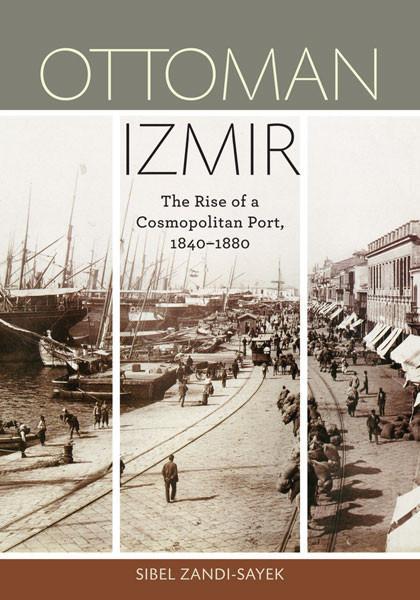

‘Ottoman İzmir: The Rise of a Cosmopolitan Port, 1840-1880’ by Sibel Zandi-Sayek (University of Minnesota Press, $28, 288 pages)

‘Ottoman İzmir: The Rise of a Cosmopolitan Port, 1840-1880’ by Sibel Zandi-Sayek (University of Minnesota Press, $28, 288 pages)

Somebody tried to convince me the other day that İzmir is the “pearl of Turkey,” part of a kind of Turkish Riviera on the Aegean. It was late and he was drunk, but I’ve heard the same thing from plenty of others. Usually I try to hold my tongue; modern-day İzmir may well be a secular, sun-drenched city, favorably perched on the Aegean, but it’s also a stifling concrete jungle, economically declining, with barely a trace remaining of its illustrious history. Known for most of its history as Smyrna, İzmir was once a dizzying array of ethnicities, religions, and languages. The second largest city in the empire after Istanbul, it was perhaps the cosmopolitan Ottoman port city par excellence, part of a broader Levantine/Mediterranean world that had for centuries been connected through trade.

Ottoman Greeks, Muslims, Armenians and Jews, and colonies of Venetian, French, Dutch, and British merchants coexisted as separately governed communities. Premised on diversity, the Ottoman social order allowed them to preserve their identities and the differential customary rights, duties and privileges associated with those identities. But this old arrangement came under increasing pressure in the 19th century, as the Ottoman state implemented a series of modernizing, centralizing reforms in response to the ascendance of the European powers. This book, written by Sibel Zandi-Sayek, a U.S.-based professor of art history, focuses on the seismic social and political effects of these reforms in İzmir from 1840 to 1880. It was a time of enormous disruption to everyday life; as visiting French parliamentarian Charles Rolland observed in 1852:

This city, which for centuries saw no other turmoil than fires, seems transformed into an arena of debates and experiences … past and future, Reformists and Conservatives are warring; and I find among all of my acquaintances, Turkish or Christian, an excitement, even an asperity of speech when interests are at stake.

Zandi-Sayek sets out to reveal how the physical and the political are indissociable, foregrounding İzmir’s built environment and public space as a crucible in which local actors vied to shape urban policies and practices and assert or preserve their positions of influence. As elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire through the 19th century, İzmir’s property regime, streets, waterfront, feasts, and rituals became a battleground for the reformist state, rival foreign powers, and various local groups. This was also when the first modern municipalities were established across the empire, rationalizing urban services by consolidating them under one management and control. The cleaning, paving, lighting, regularization, and policing of the streets became the exclusive province of a single, centralized municipal authority, replacing the “old patchwork of autonomous and often unconnected local institutions providing public services.” All this was in line with the wider “Tanzimat” reforms, which saw the old permeable subjecthood regime, based on accommodative practices, gradually replaced by one of modern citizenship that - like its European counterparts - was far more rigid and exclusive. This shift from the old informal organization of urban life to the modern, centralized system, created new tensions, threats and opportunities for local groups, which are all detailed carefully by Zandi-Sayek.

Among the most interesting sections of the book comes towards the end, with a chapter on changes to how religious and imperial feasts and rituals were marked during the period. Although religious feasts had always been an important part of communal life, in the 19th century these enactments took on a new significance, offering non-Muslim subjects new and unique opportunities for communal self-definition. Meanwhile, imperial feasts and processions were used by the Tanzimat authorities to forge a more cohesive polity from the empire’s disparate strands. Like other heterogeneous empires facing the challenge of modernization, Ottoman statesmen engaged in campaigns to bring multiconfessionalism under one political umbrella. At the same time, this interacted uniquely with the dynamics of communal assertion, as each local community jostled for favor and power, lavishing energy on extravagant expressions of allegiance to the state, regardless of actual loyalty.

This period of the city’s history has generally received little attention from historians, who have focused more on the collapse of the Ottoman city, the Greek military invasion and occupation, and the expulsion of the local Orthodox population. Of course, a cataclysmic fire engulfed the city as the Greeks were driven out and the Turks advanced in 1922, and with that fire the topography studied in Zandi-Sayek’s book went up in smoke. With its minorities also gone, İzmir became a kind of tabula rasa for the new Turkish Republic, but this book is a fascinating study of the changes it witnessed before all that happened.

‘Ottoman İzmir: The Rise of a Cosmopolitan Port, 1840-1880’ by Sibel Zandi-Sayek (University of Minnesota Press, $28, 288 pages)

‘Ottoman İzmir: The Rise of a Cosmopolitan Port, 1840-1880’ by Sibel Zandi-Sayek (University of Minnesota Press, $28, 288 pages) Somebody tried to convince me the other day that İzmir is the “pearl of Turkey,” part of a kind of Turkish Riviera on the Aegean. It was late and he was drunk, but I’ve heard the same thing from plenty of others. Usually I try to hold my tongue; modern-day İzmir may well be a secular, sun-drenched city, favorably perched on the Aegean, but it’s also a stifling concrete jungle, economically declining, with barely a trace remaining of its illustrious history. Known for most of its history as Smyrna, İzmir was once a dizzying array of ethnicities, religions, and languages. The second largest city in the empire after Istanbul, it was perhaps the cosmopolitan Ottoman port city par excellence, part of a broader Levantine/Mediterranean world that had for centuries been connected through trade.

Somebody tried to convince me the other day that İzmir is the “pearl of Turkey,” part of a kind of Turkish Riviera on the Aegean. It was late and he was drunk, but I’ve heard the same thing from plenty of others. Usually I try to hold my tongue; modern-day İzmir may well be a secular, sun-drenched city, favorably perched on the Aegean, but it’s also a stifling concrete jungle, economically declining, with barely a trace remaining of its illustrious history. Known for most of its history as Smyrna, İzmir was once a dizzying array of ethnicities, religions, and languages. The second largest city in the empire after Istanbul, it was perhaps the cosmopolitan Ottoman port city par excellence, part of a broader Levantine/Mediterranean world that had for centuries been connected through trade.