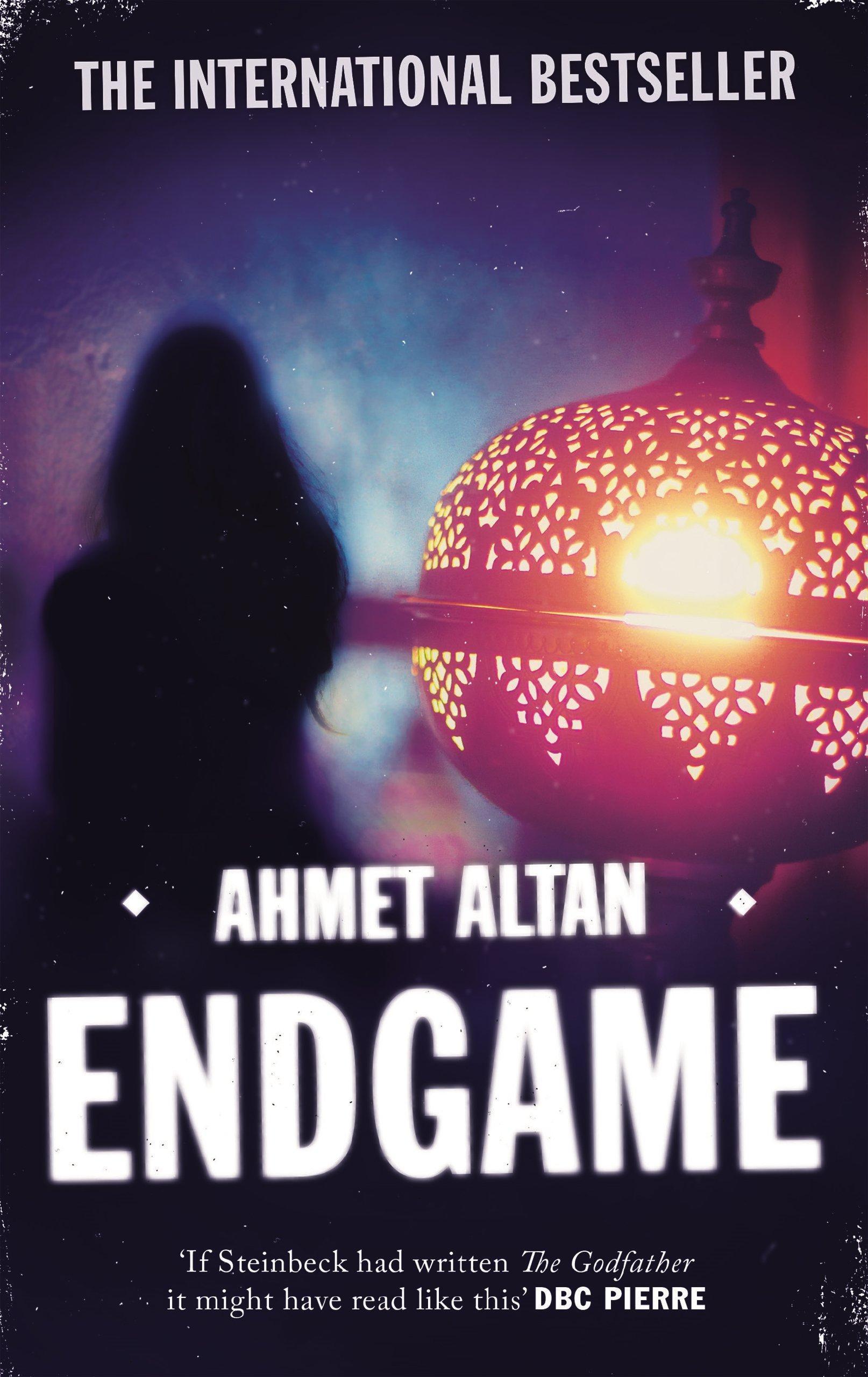

‘Endgame’ by Ahmet Altan

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Endgame’ by Ahmet Altan (Canongate, £13, 384 pages)

‘Endgame’ by Ahmet Altan (Canongate, £13, 384 pages)Ahmet Altan is best known in Turkey for his period as editor-in-chief of daily Taraf from 2007 to 2012. During Altan’s controversial tenure, the newspaper published a blockbuster series of documents purporting to show how Turkey’s shady “deep state” was plotting to foment chaos to justify overthrowing the government. It soon became clear that much of the evidence was fabricated and Taraf’s editors failed to conduct rudimentary checks on the documents - either innocence bordering on the criminal or actual criminal distortion. The revelations through which Taraf made its name obscured a crude power grab under the guise of democratization. Today they stand as a blot on Turkey’s legal and political history, prompting a hysterical witch-hunt and perpetuating a political culture of impunity and cynical calculation.

Some who worked with Altan at Taraf are now in exile, others were arrested, others turned 180 degrees and protected their positions in the pro-government press. As the poet Murathan Mungan has said, “In Turkey you can be anything, but you can’t be disgraced.” Altan himself returned happily to writing novels, which he was doing long before his time at the helm of Taraf. When “Endgame” appeared in Turkish in 2013, it was his first novel in almost 10 years. Perhaps his skills got rusty over his time off; it is not a very impressive return.

The novel is narrated by an unnamed author who has retired to a small town near the coast to work on a book. Hoping for a quiet life, he instead finds a world of suspicion, paranoia and violence, where “fear was like an infectious virus, spreading with every exchange.” He seduces women and half-inadvertently gets embroiled in bitter power struggles among the town’s notables. Online, he scratches away at some of the dark secrets lurking under the surface of apparently ordinary locals.

Throughout the book, you get the unpleasant impression that Altan is living out self-mythologizing fantasies through the main character: A womanizing alpha male living dangerously in a precarious situation, (probably how Altan likes to imagine himself). As one woman coos after reading one of the narrator’s novels: “You get women just right. You get the way we think.” Another asks him with a straight face: “Have you been with many women? Is that how you know them so well?” Even if Altan is not living vicariously through his protagonist, it is all rather charmless.

The local notables jostle over a treasure trove thought to be buried under an old church on a hill overlooking the town. This treasure is the centre of power, whether or not it actually exists. Altan closely observed Turkey’s recent political struggles, and “Endgame” may be intended as a kind of allegory, with the unnamed town a refracted microcosm of the country itself and with the narrator “waiting in the front row to watch the execution like the drunken vultures at the guillotines of the French Revolution.” Perhaps the most convincing aspect of the book is its depiction of double-crossing local heavies, dishing out favors to grease the wheels and backing themselves up with mafia-like armed retinues. Their disagreements “spread throughout the town, seeping into daily life.”

But if the novel is indeed intended as an allegory, it doesn’t really come off. The narrator’s bizarre online relationship with the girlfriend of the mayor is never convincing, despite whole chapters devoted to their tedious exchanges of messages. “Endgame” may be obsessed with the idea of what lurks beneath the surface, but its rigid division between online and offline life already seems dated.

The whole thing badly lacks original style and the dialogue is rarely believable. Translator Alexander Dawe cannot be blamed; little can be done with honking sentences like “Writers spend their lives struggling to conceal this murderous desire from other mortals,” or “Suddenly the reality dawned on me. I was sleeping with the women of the town’s two most powerful and most dangerous men.”

“Endgame” is billed as a page-turning thriller, but by the end you only feel relief to turn the last of those pages.

* A shorter, edited version of this review appeared in the Times Literary Supplement.

‘Endgame’ by Ahmet Altan (Canongate, £13, 384 pages)

‘Endgame’ by Ahmet Altan (Canongate, £13, 384 pages) Throughout the book, you get the unpleasant impression that Altan is living out self-mythologizing fantasies through the main character: A womanizing alpha male living dangerously in a precarious situation, (probably how Altan likes to imagine himself). As one woman coos after reading one of the narrator’s novels: “You get women just right. You get the way we think.” Another asks him with a straight face: “Have you been with many women? Is that how you know them so well?” Even if Altan is not living vicariously through his protagonist, it is all rather charmless.

Throughout the book, you get the unpleasant impression that Altan is living out self-mythologizing fantasies through the main character: A womanizing alpha male living dangerously in a precarious situation, (probably how Altan likes to imagine himself). As one woman coos after reading one of the narrator’s novels: “You get women just right. You get the way we think.” Another asks him with a straight face: “Have you been with many women? Is that how you know them so well?” Even if Altan is not living vicariously through his protagonist, it is all rather charmless.