An orientalist bore

William ARMSTRONG - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Constantinople’ by Edmondo De Amicis, translated by Stephan Parkin (Alma Classics, $15, 279 pages)

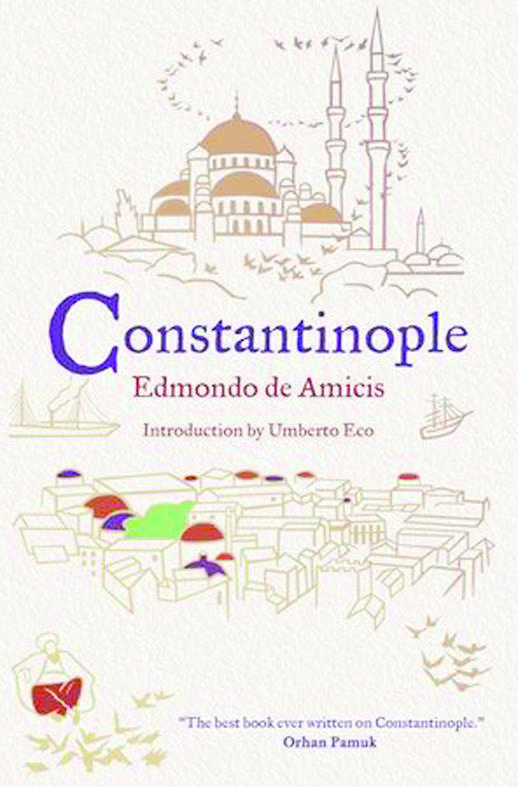

‘Constantinople’ by Edmondo De Amicis, translated by Stephan Parkin (Alma Classics, $15, 279 pages)This volume of travel notes by 19th century Italian bon vivant Edmondo De Amicis ticks all the right boxes for the publisher. The jacket has a nice design; an admiring quotation from Orhan Pamuk adorns the cover; it has an introduction written by fellow postmodern cosmopolitan Umberto Eco. The book looks sure to succeed as an esoteric guide for more discerning tourists to modern day Istanbul. Unfortunately, however, it’s a complete bore - a verbose parade of “quaint” 19th century orientalism full of annoyingly purple prose that is amusing for about one paragraph. The perennially overwhelmed De Amicis writes at one point: “When you try to describe this chaos in words – then you’re tempted to bundle up all the books and papers on your table and throw the whole lot out the window.” It’s a shame he didn’t succumb to that temptation.

De Amicis visited Constantinople in 1874, at a time when ever more European travelers were making their way to the city - perched conveniently close on the edge of Europe, it was an easily accessible slice of orient. Still, it isn’t clear what distinguishes De Amicis’ memoir from the dozens of similar tomes written by intrepid Europeans at the time. Certainly it isn’t for the profundity of his historical perspective: De Amicis does little other than describe all the exotic sights that assailed him in the city, making hardly any attempt to interpret them or place them in any broader context, simply offering bromides about “the Turk.” For all the “exotic,” “sensuous,” “ravishing” quality of what he’s describing, it all remains rather texture-less for the reader. Such a heavy emphasis on the surface of things might be bearable if it was edited down into a slimmer volume – perhaps concentrated in a single short piece – but this simply drags on and exhaustingly on. Where’s the editor?

De Amicis visited Constantinople in 1874, at a time when ever more European travelers were making their way to the city - perched conveniently close on the edge of Europe, it was an easily accessible slice of orient. Still, it isn’t clear what distinguishes De Amicis’ memoir from the dozens of similar tomes written by intrepid Europeans at the time. Certainly it isn’t for the profundity of his historical perspective: De Amicis does little other than describe all the exotic sights that assailed him in the city, making hardly any attempt to interpret them or place them in any broader context, simply offering bromides about “the Turk.” For all the “exotic,” “sensuous,” “ravishing” quality of what he’s describing, it all remains rather texture-less for the reader. Such a heavy emphasis on the surface of things might be bearable if it was edited down into a slimmer volume – perhaps concentrated in a single short piece – but this simply drags on and exhaustingly on. Where’s the editor?Of course, De Amicis traveled to the Ottoman capital at a very interesting time, as the empire was stagnating and modernizing reforms were being introduced to reinvigorate it. Visual evidence of the Westernization process was everywhere on the streets where he walked, and it’s telling that he can generally only focus on these most superficial, surface reflections of profound change:

Today we catch them in a process of transformation … The inflexible old Turk still wears the turban, the kaftan and the traditional slippers of yellow morocco leather; and the more obstinate the man, the bigger his turban. The reformed Turk wears a long black frock coat buttoned to the chin, dark trousers with spats, and nothing Turkish but the fez … Every year sees the fall of thousands of frock coats; every day an old Turk dies, and a reformed Turk is born. Newspapers replace tesbihs, cigars rather than chibouks are smoked, wine is drunk instead of sugared water; the coach displaces the araba; French not Arabic grammar is studied; pianos take the place of timbrels and houses are built of stone rather than wood.

He rarely dives deeper than this, typically restricting himself to expressions of overawed wonder: “Should anyone ask you: ‘What is Constantinople like?’ you could only grasp your head in your hands and try to still the storm of thoughts. Constantinople is a Babylon, an entire world by itself, a chaos. Beautiful? Wonderfully beautiful. Ugly? It is horrible! Did you like it? Passionately.” Raises a chuckle as a throwaway passage? Imagine it going on for 250 pages.