After Sykes-Picot: Britain, France and the struggle for the Middle East

William ARMSTRONG - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the Struggle that Shaped the

Middle East’ by James Barr (Simon & Schuster, 454 pages, $25)

‘A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the Struggle that Shaped the

Middle East’ by James Barr (Simon & Schuster, 454 pages, $25) In June this year, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) posted photographs of its fighters demolishing barriers marking the border between Syria and Iraq. The jihadists declared that they were “smashing the Sykes-Picot border,” referring to the 1916 Anglo-French agreement that divided the Ottoman Empire’s Arab dominions into mutual zones of influence. ISIL’s release was a typically savvy attempt to win the support of disaffected Arabs, but perhaps more surprising is the way that the post-Sykes-Picot narrative has struck a chord in the West. Many appear convinced that the origins of the Middle East’s myriad problems today can be found in the supposedly arbitrary borders drawn up by the imperial powers during the First World War. The solution, they imply, lies in a new arrangement better suited to the “authentic” historical character of the region.

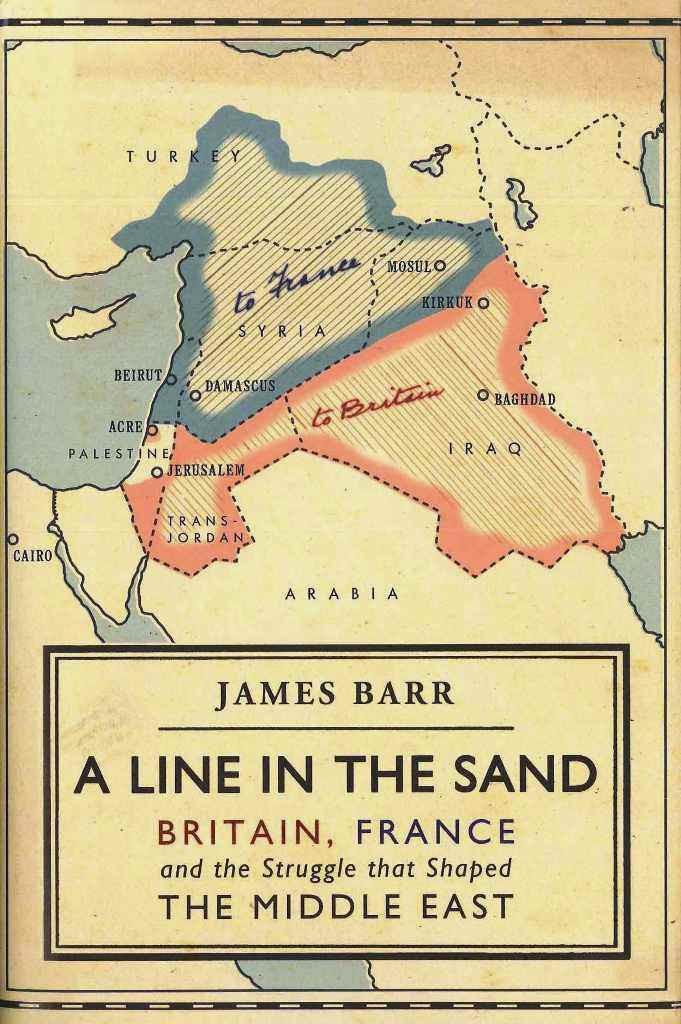

In June this year, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) posted photographs of its fighters demolishing barriers marking the border between Syria and Iraq. The jihadists declared that they were “smashing the Sykes-Picot border,” referring to the 1916 Anglo-French agreement that divided the Ottoman Empire’s Arab dominions into mutual zones of influence. ISIL’s release was a typically savvy attempt to win the support of disaffected Arabs, but perhaps more surprising is the way that the post-Sykes-Picot narrative has struck a chord in the West. Many appear convinced that the origins of the Middle East’s myriad problems today can be found in the supposedly arbitrary borders drawn up by the imperial powers during the First World War. The solution, they imply, lies in a new arrangement better suited to the “authentic” historical character of the region.There’s no doubt that the secret Sykes-Picot agreement was an arrogant, shamelessly self-interested pact even by the standards of the time. According to a contemporary of one of its co-authors, British official Mark Sykes, the border was “drawn with a stroke of a pencil across a map of the world,” while the head of British military intelligence described the two sides as being “in the position of the hunters who divided up the skin of the bear before they had killed it.” However, as a hypothetical division of a region that neither of its signatories yet controlled, the agreement was also highly vulnerable to events and local conditions. Indeed, the borders - which demarcated recognizable historical spaces, and which were just as arbitrary as borders in anywhere - shouldn’t themselves be seen as the problem; attention should rather be drawn to subsequent Western policies that were often responsible for crippling states in the region.

The title “A Line in the Sand” might suggest otherwise, but British writer James Barr’s book does just that. The author starts by focusing on Sykes-Picot, but only as a launchpad to examine the often venomous Anglo-French rivalry in the region in the first decades of the 20th century. It’s a story full of imperial skullduggery and shameful details, which Barr interrogates with a journalist’s instinct to assume that all involved were acting out of the very worst motivations. He deftly negotiates the tangled web of diplomatic relations, exposing the chasm between both powers’ lofty rhetoric of enlightened civilization and their cynical maneuvering; I frequently caught myself open mouthed while reading about the breathtaking flagrancy of all involved; as Barr himself drily observes, “it’s a tale from which neither country emerges with much credit.”

The Sykes-Picot agreement was overtaken by events almost as soon as it was signed, and the British and the French were forced to find new ways to guard their interests in the region. For the British, the priority was to secure the Suez Canal to the west and protect oil resources in Mesopotamia; for the French, it was to maintain access to the Eastern Mediterranean to protect their cultural and commercial ties (and thus national prestige). To achieve their aims, both sides struck alliances with various local groups, which found themselves in the position of chess pieces, shifted around according to the changing conjecture. Both France and Britain were incurably suspicious that the other was sabotaging their plans, often with good reason.

Most of Barr’s research was already well known before he wrote the book, but truly original detective work comes during his passages on the Second World War. Through dogged excavation of the archives, he reveals incontrovertible evidence of clandestine links between a number of Zionist terrorist groups targeting the British administration in Palestine and Free French officials at the time. The Zionists were angry at the British for limiting Jewish immigration in order to placate local Arabs, and hardliners staged a series of bloody attacks - apparently supported by French intelligence and logistical assistance - in a bid to oust the British from the Holy Land. The French, in Barr’s account, were motivated by a lust for revenge against the English, and a wish to give a bloody nose to the Arab League, which threatened its interests in North Africa.

The lasting impression left by the book is of a grim stream of rebellions, suppression, betrayal and bloodshed. Its final chapter ends with a droll quotation from Sir John Shaw, the former chief secretary of Palestine, European mandates for Arab states:

“If you look at it from a purely philosophical, high-minded point of view, I think it’s not only immoral but it’s ill-advised … because it’s not your business or my business, or British business, or [for] anybody else to interfere in other people’s countries and tell them how to run it, even to run it well. They must be left to their own salvation.”Coming after 400 pages of insidious Great Power intrigue, those words carry a rather plaintive hue.