What next, after censoring Turkish Parliament on corruption?

For the first time in Turkey, a court has put a media ban on a parliamentary inquiry into corruption allegations against four former Cabinet members of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Parti), scheduled to start on Nov. 26.

The ruling of the 7th Ankara Magistrate Court, as it was first reported by daily Cumhuriyet, came after a letter sent to the prosecutor’s office on the basis that publications about the inquiry could violate the “presumption of innocence” principle of the four former ministers.

The former ministers - namely Muammer Güler (interior), Zafer Çağlayan (economy), Erdoğan Bayraktar (environment and urbanization) and Egemen Bağış (European Union affairs) - are all protected by constitutional immunity, and could only be tried if Parliament votes that their trial is necessary after the inquiry.

They are all accused of being involved in a bribery ring with Iranian-origin businessman Reza Zarrab, (Rıza Sarraf after adopting Turkish citizenship), who was involved in gold-for-oil trade with Iran (under sanctions), in a corruption probe opened on Dec. 17, 2013 by an Istanbul criminal court.

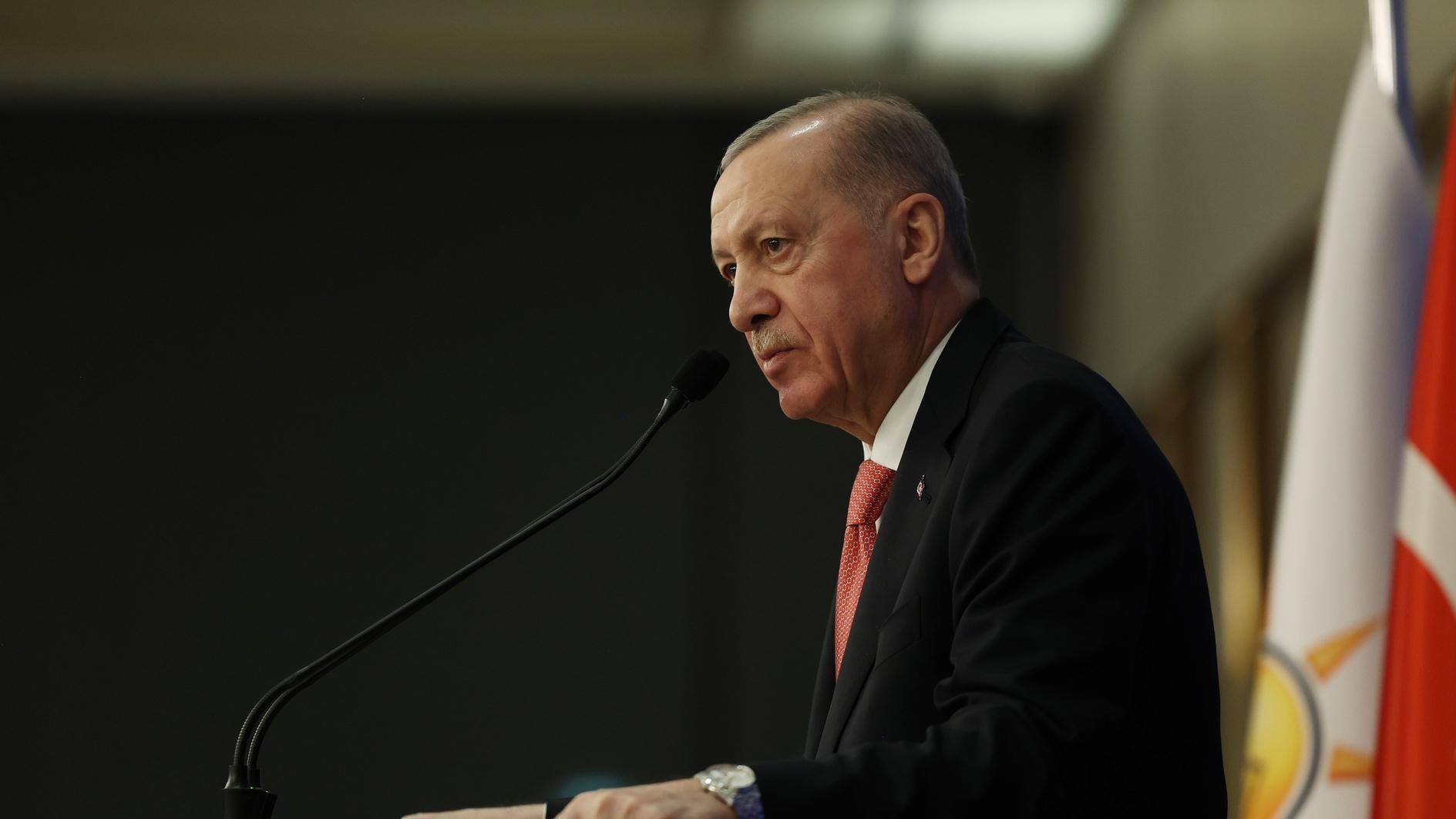

Later on (then Prime Minister, now President) Tayyip Erdoğan removed all four from the Cabinet, but declared that the whole probe was a plot concocted by a network in the judiciary and the police force run by sympathizers of his former ally, U.S.-based Islamic scholar Fethullah Gülen, in order to overthrow his government.

That triggered a series of legislative changes, especially for the judicial system, as well as shifts in the positions of prosecutors and judges, and the newly assigned prosecutors and judges eventually dropped all charges against those accused in the Dec. 17 and later Dec. 25 graft probes.

However, in the meantime Parliament had already decided to open inquiries against the four former ministers.

The AK Parti holds a majority in the inquiry commission anyway, so it would not be a huge prophecy to say that the commission’s vote, which must be finalized by Dec. 27, 2014, will see no reason for a trial to be held.

Nevertheless, it seems that neither the AK Parti nor the AK Parti-origin parliamentary speaker wants to risk even a debate about the corruption allegations, or the defenses of the ex-ministers to be heard by the public. It is hard to interpret the effort to impose the ban on reporting the commission in any other way.

Reactions against the ban have come from opposition parties and some newspapers and agencies that said they would defy it and report the commission’s work. Deputies of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) are planning to publish the content of the commission’s work by taking to the parliamentary floor and putting it on the public record, at least.

But the move to impose the ban is worrying regarding the state of transparency, accountability, the fight against corruption and quality of democracy in Turkey. Certain questions come to mind, such as “What’s next?”