CHP wants to make a new start with Kurds

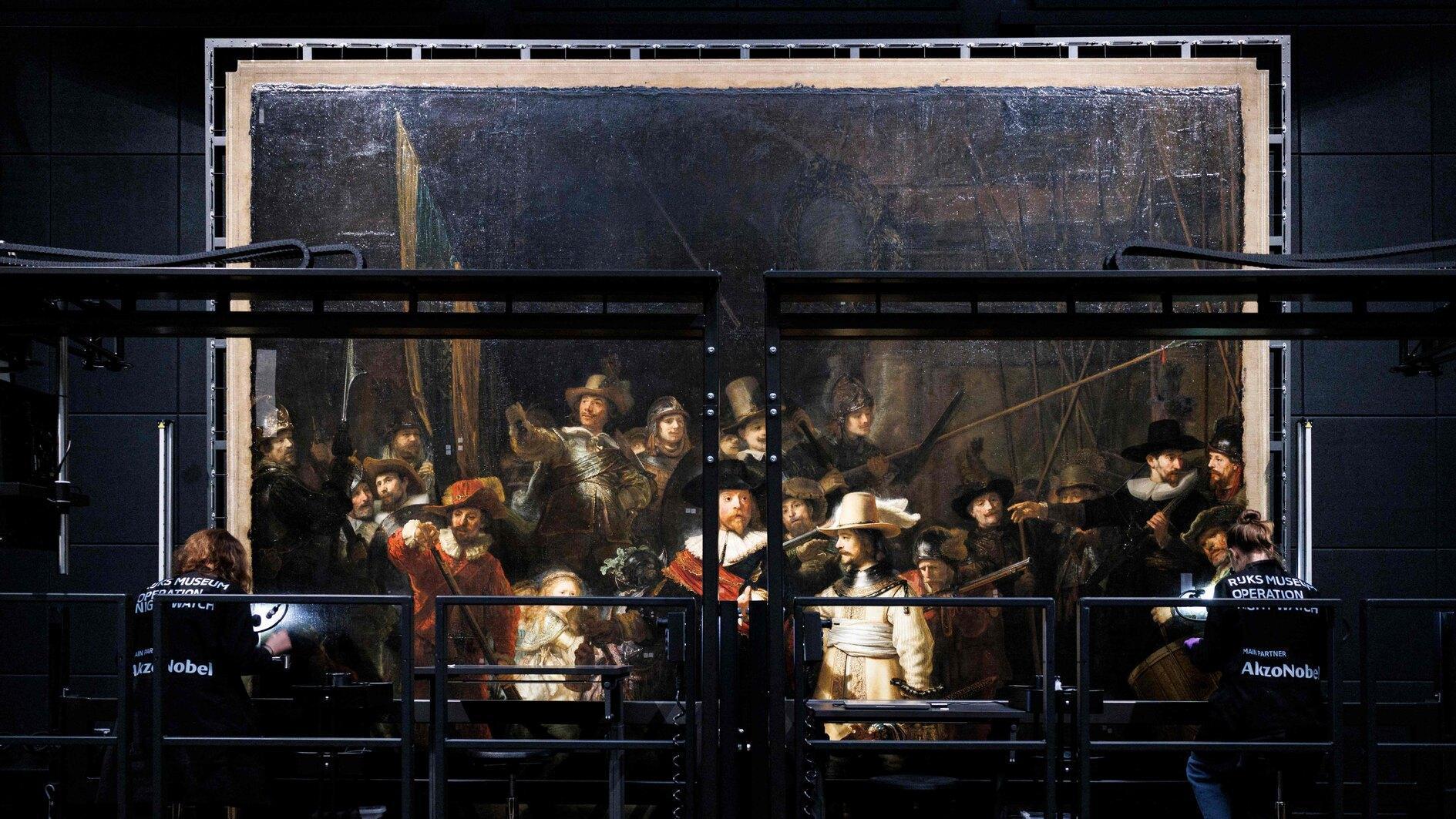

Republican People’s Party (CHP) leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu holds a little girl as he speaks to citizens at the historic Hasan Paşa Han in Diyarbakır. AA photo

“I am happy with the meeting. I want to see this step as the start of dialogue between us” said Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of Turkey’s social democratic main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), while sipping his after-dinner tea following a four-hour-long conference in Diyarbakır on June 20.It was now time for a chat over a couple of tulip-shaped glasses of tea.

The representatives of around 60 groups, not only from Diyarbakır but from all predominantly-Kurdish provinces of east and southeast Turkey, were there in the restaurant of the hotel hosting the meeting. It was organized by the Diyarbakır-based think-tank the Tigris Communal Research Center (DİTAM) at a very critical time, when Kurdish politics play a crucial role in both Turkish foreign policy in the civil war struck southern neighbors of Syria and Iraq and in the domestic scene as the country heads to a first round of presidential elections on Aug. 10.

The representatives of mostly Kurdish NGOs grilled the opposition leader over his party’s policies on the Kurdish problem. Kılıçdaroğlu listened to them calmly, took notes, and answered them one by one.

During the dinner, jokes were made around the table about what would happen if just a quarter of the questions - which often contained harsh criticism - were asked to Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan, who has demonstrated before that there is a limit to his patience.

Not everyone was sitting around the same dinner table of course, but those reflecting the pulse of the region were there.

One of them, Cabbar Leygara, is a lawyer and a well-known Kurdish activist in Diyarbakır, and was representing the Democratic Society Congress (DTK), a multi-party based group inspired by the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), conducting legal work for more rights for Kurds. “We heard what you said today,” Leygara said. “About how you also want the government’s initiative for the Kurdish dialogue process to be carried to Parliament in order to give it legal bases and in order for it to be transparent. We believe that the CHP should be a part of dialogue process as well. But there are lots of other voices in your party, which makes it difficult for us to explain to the people on the street here.”

“I said in the conference as well: There may be other freely-voiced opinions in our party, but only the words of the chairman and the party administration have binding power. But I hear what you say. We must come here more often and get into a face-to-face dialogue with people,” Kılıçdaroğlu replied.

“Send your MPs from Western provinces, from İzmir for example” said Leygara with irony, hinting at Birgül Ayman Güler, who caused controversy a few months ago with much-debated words comparing Turkish and Kurdish rights. “We’d also like to see them here to talk to us.”

“Perhaps we can come together next time,” Kılıçdaroğlu replied, taking another sip from his glass of tea.

“Would you consider having your CHP party assembly meeting here in Diyarbakır? So that perhaps we can answer their questions and worries directly,” said Mehmet Kaya, the head of DİTAM and also a renowned businessman in Diyarbakır.

“Why not?” Kılıçdaroğlu said. “We can consider that. Don’t forget that we don’t want to discriminate between the rights of groups. We want more democratic rights for everyone, which is why we are asking for your support.”

In this same hotel, under a different name at the time, Deniz Baykal, the former chairman of the CHP, convened his party’s Central Decision Board (MYK) meeting in June 2008. That meeting turned out to be a major fiasco, after one group threw rotten eggs and tomatoes at him and the CHP bus in order to stop them from even walking on the streets of Diyarbakır, let alone contacting the locals.

In 2010, Kılıçdaroğlu visited Diyarbakır to make a public speech – though only to a few hundred locals, despite the fact that PM Erdoğan can gather tens of thousands, mostly religious, conservative Kurds - and showed up in the streets of the city, sitting and playing backgammon with young people in coffee houses.

However, that did not help the CHP, which only got around 1 percent of Diyarbakır’s votes in the local elections on March 30, 2014. Diyarbakır used to be one of the CHP’s bastions during the mid-1970s under Bülent Ecevit, who had managed to underline the social democratic principles of the party, rather than its etatist line that prevailed during the 1990s. The Kurdish nationalist and conservative vote potential grew as the CHP shrunk in the cruel atmosphere of the PKK’s guerrilla campaign, starting from 1984, and the security forces’ reply with an awful record of human rights violations. The conflict claimed the lives of nearly 40,000 people until Erdoğan’s dialogue initiative started in 2012.

In a major difference from his earlier experience in Diyarbakır, Kılıçdaroğlu made wide public appearances this time, visiting the city’s historic bazaar and talking to the shopkeepers and citizens on the streets.

Now as Turkey has presidential and parliamentary elections in sight, he is asking for the support of the Peoples’ Democracy Party (HDP), which shared a power base with the PKK, for support against the (still not official) candidate from Erdoğan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Parti). Last week, the CHP proposed a non-partisan name as its presidential candidate, Dr. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu, the former Secretary General of the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC), with support from the second largest opposition party, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).

“Your party has asked for our support in the past, too” Leygara told Kılıçdaroğlu. “But we were asked not to make it public, which was something unacceptable for us.”

“Don’t you think this time it is different? I ask for the HDP’s open support in front of the cameras; it is broadcast live. I also officially asked the HDP co-chairs during our meeting in Parliament last week. It’s all public now,” Kılıçdaroğlu said. Leygara did not object, replying only with a smile.

But it seems that it’s not easy for the CHP to convince Diyarbakır, or Kurdish voters generally. To at least be able to find a new voting potential in the region, a clearer policy line should be set, especially in the area of Kurdish language education. “Please understand this,” said Raci Bilgili, the head of the Diyarbakır branch of the Human Rights Association (İHD). “People see the Kurdish education issue as a basis for respect of their rights.”

This seems to be a delicate issue that PM Erdoğan is not forming a clear line on either. What the HDP wants is a radical change to allow education in Kurdish from primary school to university. Many others - both in government and in opposition parties - ask questions about the future of the country’s human resources and political “unity” issues in this event.

On the Kurdish front of the presidential elections, it seems that the HDP will come up with its own candidate and try its best to stop Erdoğan, or any other AK Parti candidate, from getting the necessary 50 percent-plus-one in the first round of the vote, in order to force Erdoğan to negotiate ahead of the second round on Aug. 24.

Politics is about to warm up further as Turkey gets closer to election time.