Why I felt offended by Macron’s remarks

Last week, French President Emmanuel Macron visited the Council of Europe and spoke at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). It was the first time a French president was visiting the court. “Today, we are in a situation in which several member states do not respect the terms of the [European Human Rights] Convention in a clear manner,” he said. “For example, with Turkey and Russia, which are not the only examples, the risk is evident,” he added. Despite the note that there were others in apparent violation of the convention, I find this comparison rather offensive. Why?

The Council of Europe has a broad membership of 47 countries in and around Europe, and makes non-binding decisions on European values, human rights, democracy and the rule of law. Considering the tide of right-wing populism in the continent, I can understand why the president found it appropriate to visit the institution in Strasbourg.

But let’s take a small detour into history here. The initial agreement for the Council of Europe was drafted in 1948, so before even NATO existed, and the institution was effectively established by 10 countries signing the London Agreement in May 1949. Turkey and Greece were invited as founding members in August 1949, even before Germany came in1950. The council was a place where a common post-war European identity came to be. The symbol of the yellow stars on a blue background, for example, originated here.

Russia only joined after the Cold War, in February 1996. This is the first reason why I feel offended by this comparison.

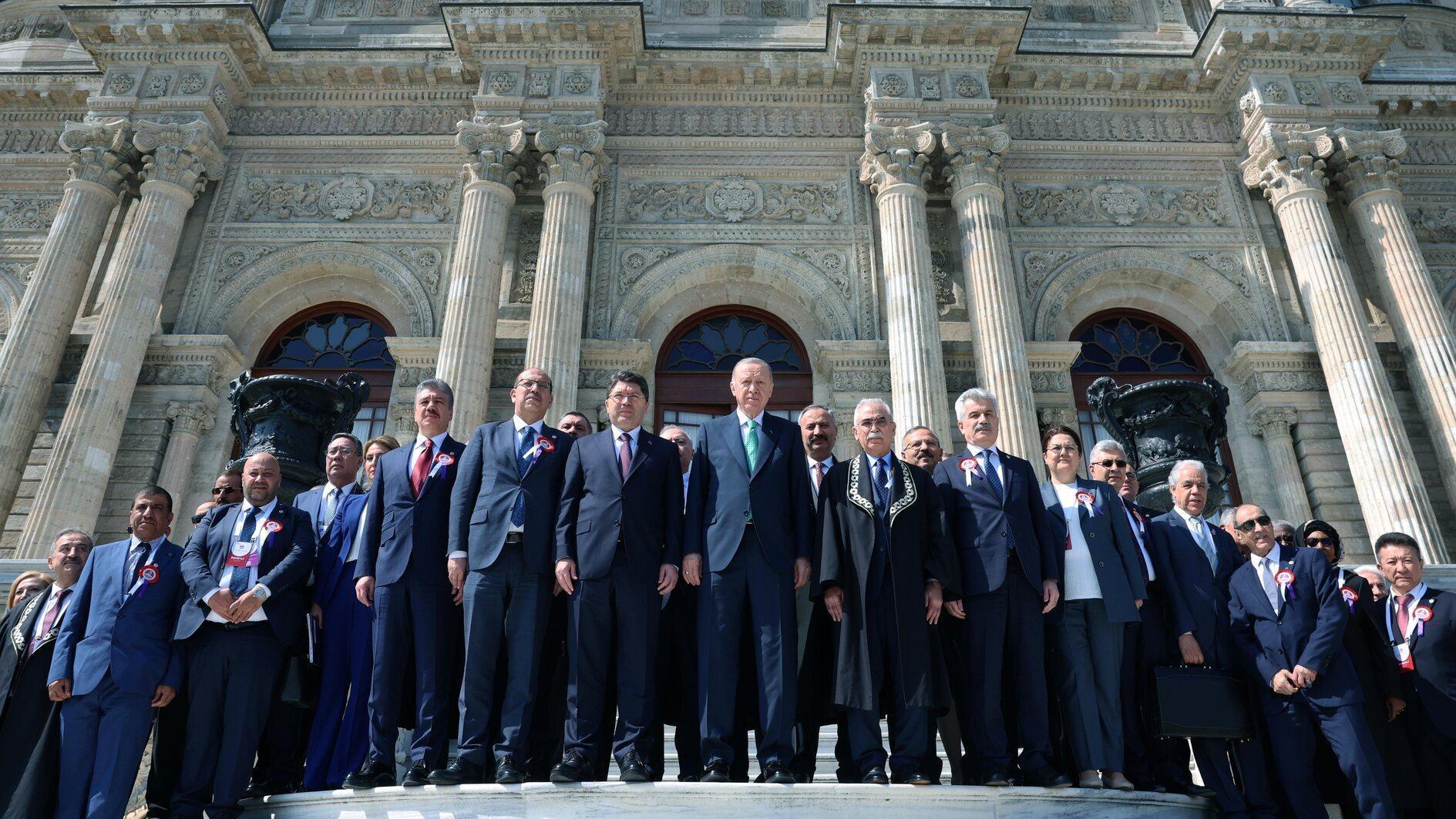

The Council of Europe was Turkey’s first institutional tie with Europe after World War II. Comparing the human rights situation in Turkey to Russia at a time like this just does not make sense. Over there, they do not even jail critical journalists, they often just kill them. Turkey does not have an impeccable record when it comes human rights and democracy, I’ll be the first to admit that. But we are no neo-Tsarist behemoth with absolutist tendencies. Only about half of Turkey’s population has ever voted for President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and the country still has high-level critical dialogue. Overlooking all this and casting us down to Russia’s level is disrespectful to democratic voices in Turkey. It also lowers the standard for the country, making it more likely that we really will one day be at Russia’s level of democratic development.

Perhaps, part of the problem is that our European friends used to think of Erdoğan as something he never was, namely a liberal. It’s not just Erdoğan, but Turkey as a whole has never been a liberal country fully complying with European values. Why then was Turkey a founding member? Cold War conditions, you might say. Turkey has been an integral part of the mechanism despite military regimes in 1960, 1971 and 1980. But I also see a track record of steady improvement over the years.

Lately, Turkey has two juxtaposed traumas our European partners have difficulty in understanding. First, the Syrian civil war poisoned the Kurdish reconciliation process and our relationship with our allies. The People’s Protection Units/Kurdistan Workers’ Party (YPG/PKK) gaining strength and legitimacy through the United States has been played into very deep fears in the Turkish public consciousness. Second, last year’s failed coup attempt has put us off balance. The combination of these two things has led to a dreadful situation in Ankara. Meanwhile, Turkey’s allies wrote the country off as a failure, which makes things worse.

Yet Turkey is no Russia for many reasons. Russia has a very large internal market, giving it more bargaining power. Turkey does not. Russia is rich in oil, Turkey is not. Russia has a current account surplus, Turkey does not. Unlike Russia, Turkey is an industrial country that needs to be an integral part of the modern world. So while Russia might have other options, Turkey does not.

There is no need for a reset in EU-Turkey relations. The European Union only needs to recall its transformational role on our continent. Its leadership needs to once again stand up for itself. The only way Europe is going to win back its periphery is to be a beacon of modernity, prosperity and confident liberalism. Everything else will follow.