Why do Turks invest so much in construction?

Since the 1980s, Turkey has transformed itself from a sleepy agricultural economy to a mid-tech industrial economy.

Since the 1980s, Turkey has transformed itself from a sleepy agricultural economy to a mid-tech industrial economy. Impressive? Yes. But it stopped there. Just have a look at the share of hi-tech products in Turkey’s exports. A lousy 4 percent, compared to the OECD average of around 18 percent.

Why? Why do Turks invest in construction rather than biotechnology? The obvious answer is often the right one: It’s about the duration of the investment. The term required to get your money back is much shorter in construction than in hi-tech endeavors. Turkey grows in volatile stop-and-go cycles, which shortens its investment horizon. So it is all about poor macroeconomic management.

Let’s have a look at the numbers. The average growth for 2002-2007, which was around 6.7 percent, halved to around 3.2 percent for 2008-2014. How about volatility in the two periods? Volatility here is just measured by the standard deviation of growth around its mean. It was around 1.8 in 2002-2007, and increased to 4.8 in 2008-2014.

So the problem is not only that growth decreased, but that our horizon has shortened since 2007. That made it harder to make well-informed investment decisions. What was the result? The construction sector powered through the tough times, leaving the rest of the economy in the dust.

But are we being too tough on the management here? The year 2008, after all, saw the biggest global recession since the Great Depression. Of course the boat was rocking - international fluctuations made it much harder to maintain macroeconomic stability in Turkey, just as in other parts of the world.

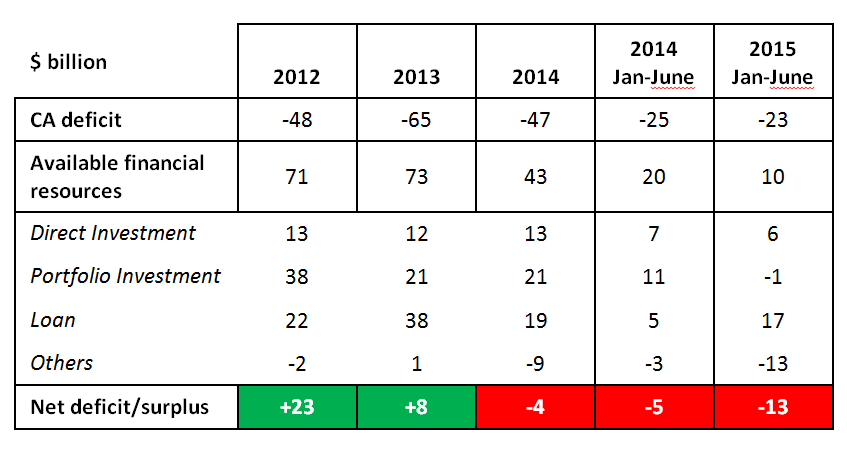

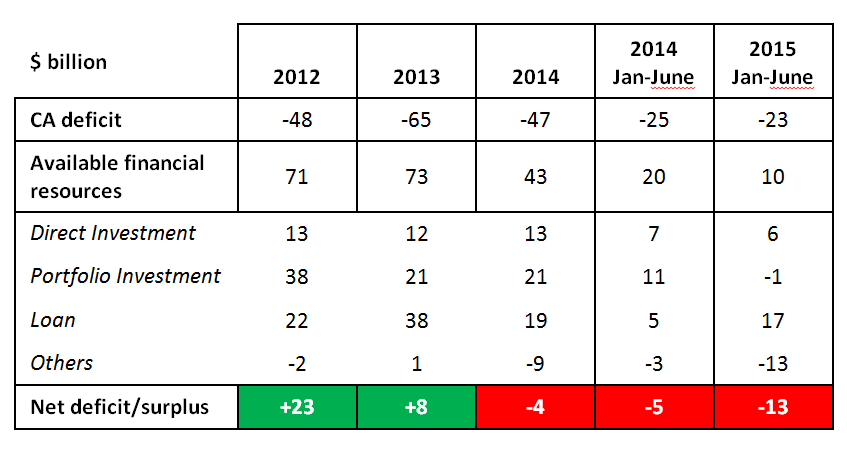

However, we would be lying to ourselves if we put the problem squarely on external factors. One look at the current account deficit shows that macroeconomic management has been a sorry sight over the past few years. While the share of Turkey’s current account deficit to GDP was around 3.8 percent in 2002-2007, it increased to 6.1 percent in 2008-2014. Sure, countries ideally borrow when things get bad, and – in what is called “countercyclical fiscal policy” - they pay back their debts in good times. But Turkey does not do that either. We borrow in good times, and then borrow more in bad times.

Just like cholesterol clogging up your veins, a high current account deficit might not lead to disaster right away, but it will deplete the most precious commodity there is: The future. If a country keeps borrowing from its future, investors will start to pull out, and the economy will spiral into deeper and deeper debt. In Turkey’s case, it shortened the country’s investment horizon, leading to an asymmetric growth boom in the already plush construction sector.

Yes, the global financial crisis certainly played a role. But it did not create Turkey’s structural shortcomings. It merely brought them to light. Let’s at least be honest with ourselves: The fault is not in our stars.

Table: Growth rate, volatility and CAD in Turkey (1980-2014)