Wild Turkey’s growing pains

At first look,

the first quarter National Income Accounts, which were released on September 10, would make even a perennial pessimist like me satisfied.

The economy grew 4.4 percent annually, exceeding expectations of 3.6 percent. The positive surprise could not have come at a better time. If you are worried, like me, that Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is

not allowing the “independent” Central Bank to hike rates, the figure could help Governor Erdem Başçı or economy tsar Ali Babacan convince him.

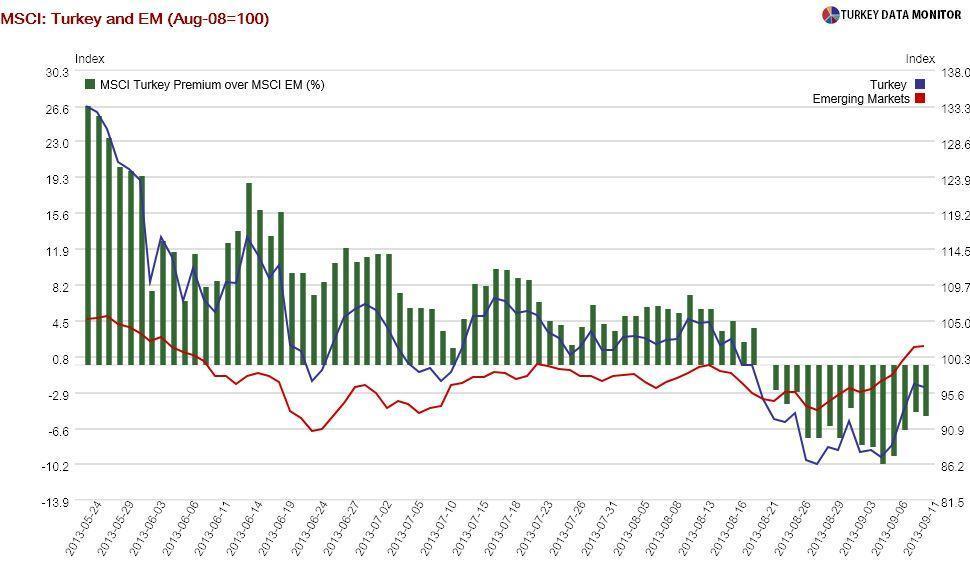

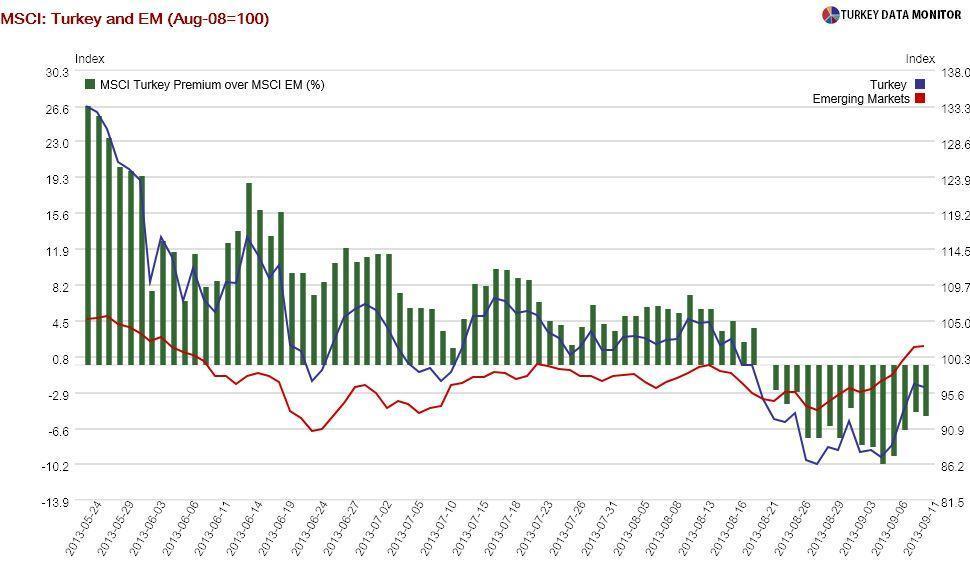

Given rising concerns on emerging markets’ growth prospects, the data may also improve investors’ perception of the country for a while. As Fed tapering worries receded after the latest U.S. nonfarm payrolls, Turkish assets have already been outperforming peers. The growth statistics could enforce this trend.

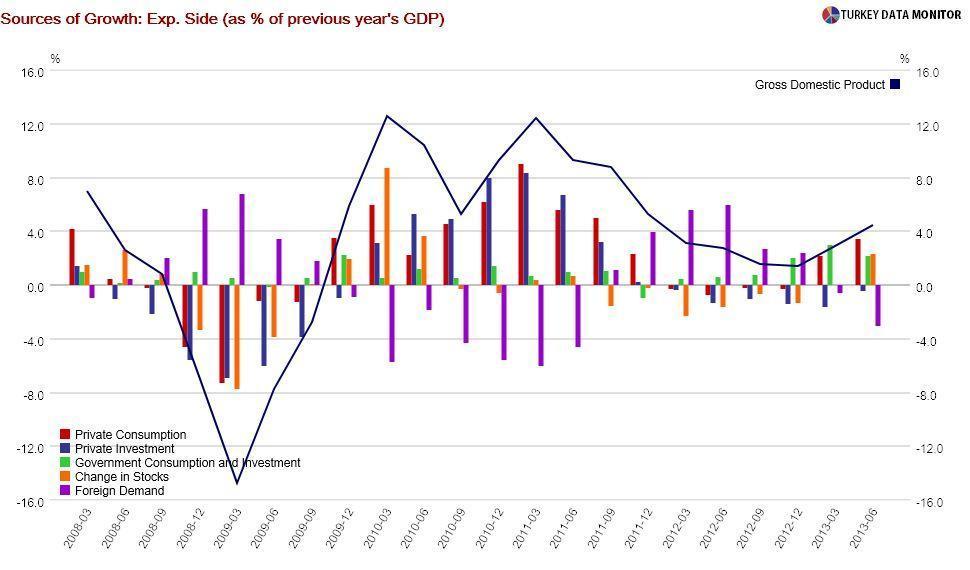

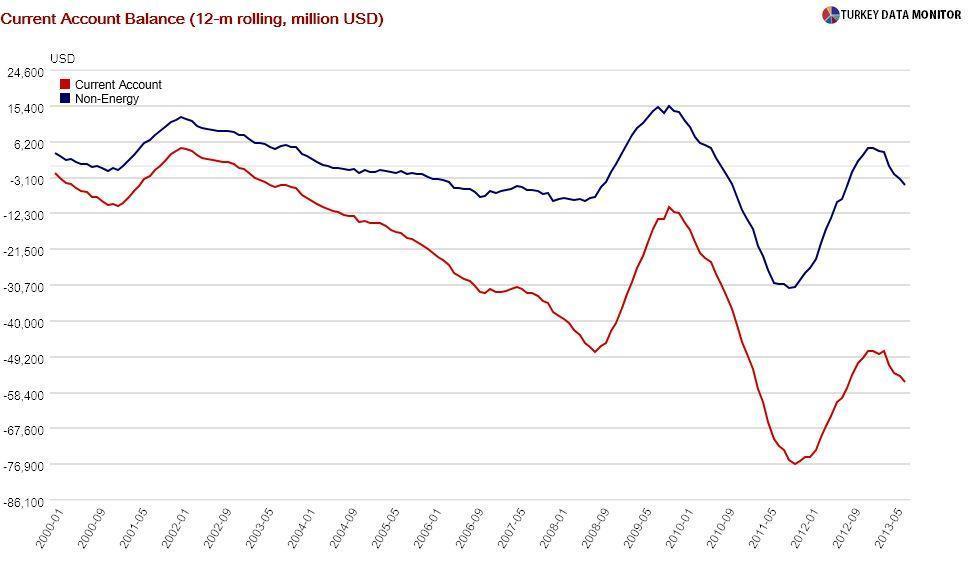

However, the details are painting a bleak picture. For one thing, consumption was the driving force behind growth, contributing 3.4 percentage points. Such reliance on consumption is reinforcing Turkey’s external vulnerabilities. At $5.8 billion, the

July current account deficit released on September 12 turned out to be higher than expectations of $5.3 billion.

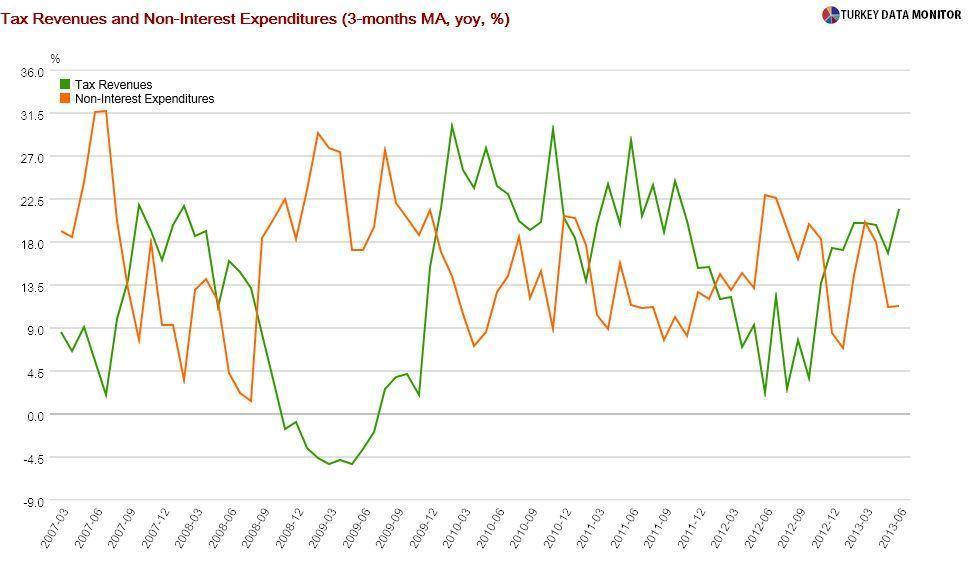

Growth also benefited from public spending and investment, which contributed 2.2 percentage points, and hopefully has

dispelled the view that the government is

running a tight fiscal ship. The robust headline budget numbers and the rise in tax revenues are hiding the increase in non-interest expenditures. The August cash budget, which was released on September 6, is hinting that this trend will continue into the local elections.

But I doubt growth will be sustainable. For one thing, stock build-up contributed 2.3 percentage points. While it is difficult to pinpoint if this was because of depleted raw materials/intermediate goods, a response to increased orders or misestimation of demand, this item is likely to contribute negatively for the remainder of the year as firms reduce their stocks.

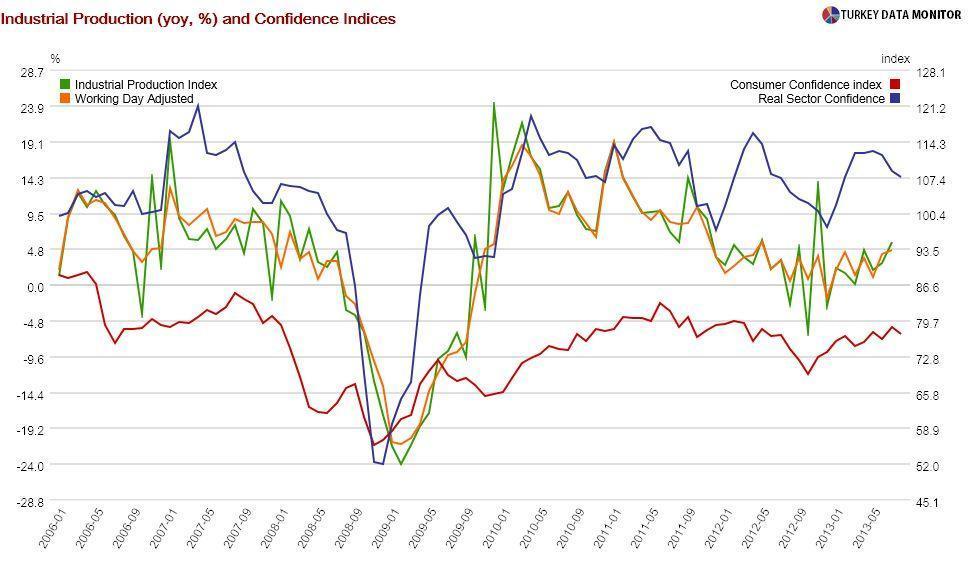

Moreover, the domestic and global environment was very conducive to growth until the end of May, with Turkish interest rates hitting all-time lows. Since then, rates have risen, consumer and business sentiments have taken a hit, and Turkish assets have tumbled.

July industrial production, released on September 9, was stronger than expected, but that series is notoriously volatile.

First quarter data are also raising alarm bells because of investment and net foreign demand, which chipped off 0.5 and 3 percentage points respectively from growth. As

economist Murat Üçer notes, “investment remains unusually weak for this stage of the recovery, and net foreign demand is turning rapidly negative even though economy/investment is not particularly strong.”

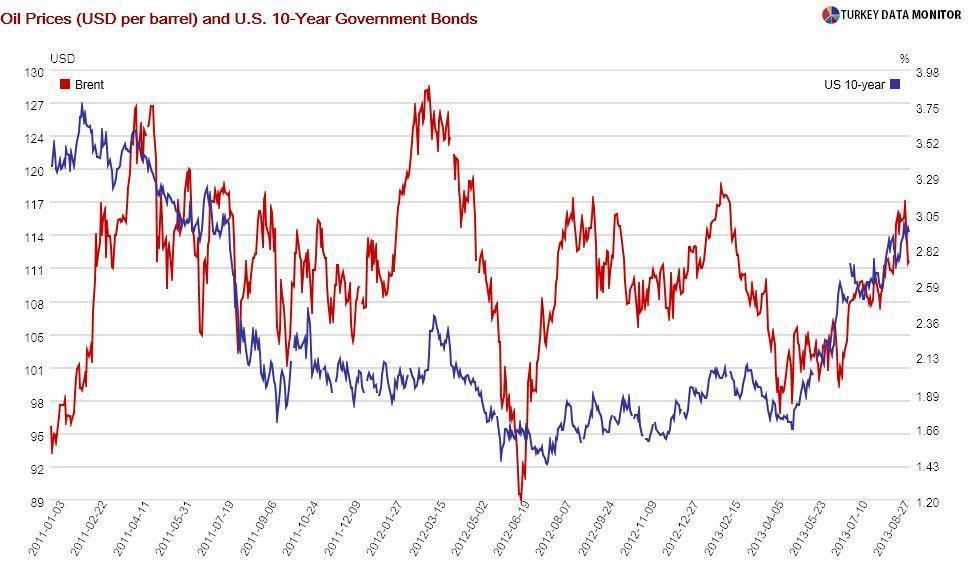

And I haven’t even mentioned the potential impact of oil prices, domestic/regional political concerns, or global economic developments. I would be more than happy if growth turned out to be 3.5 percent for the whole year. That would at least mean the economy has not crashed.

At first look, the first quarter National Income Accounts, which were released on September 10, would make even a perennial pessimist like me satisfied.

At first look, the first quarter National Income Accounts, which were released on September 10, would make even a perennial pessimist like me satisfied.