Turkish economy living on borrowed time

I looked at emerging market (EM) exchange rates against the dollar on the night of Dec. 17, right before the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) interest rate decision. The Turkish Lira was the

second most depreciated currency against the dollar, right after the Russian ruble.

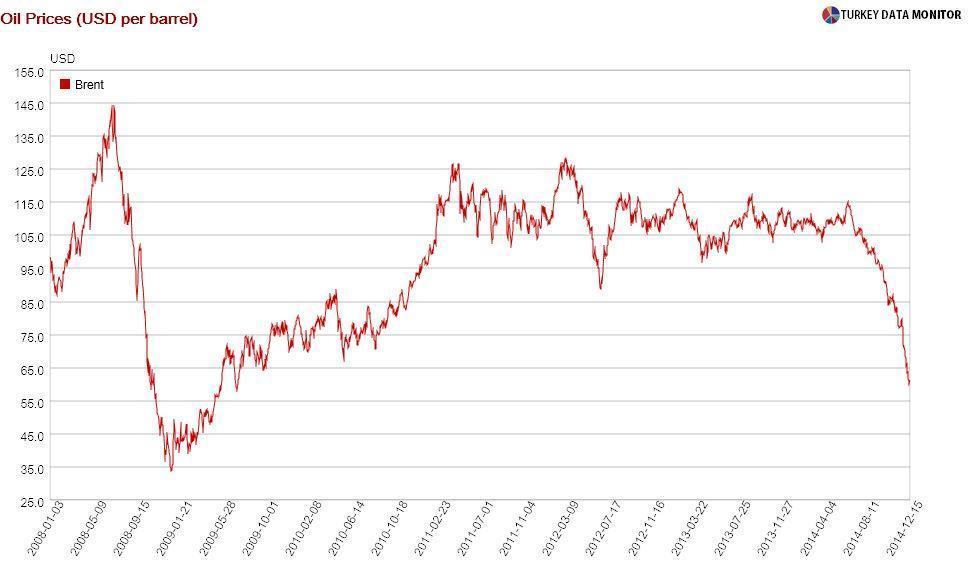

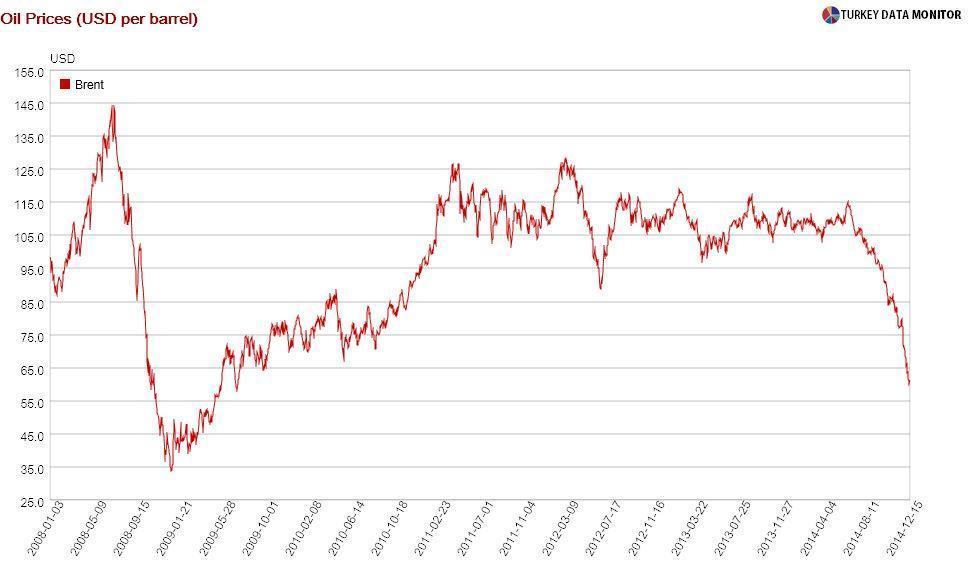

The two countries could not be more different. For one thing, Turkey, an

advanced democracy, is not ruled by an

autocratic president and a puppet prime minister. But more importantly, Turkey is an oil importer, whereas oil-exporting Russia is hurt by plunging prices. In fact, analysts were pinpointing Turkey as one of the countries

poised to benefit the most from lower oil prices.

You could argue that Turkey was hit because of its trade ties to Russia. Interestingly enough, the next three spots for the most depreciated currencies went to Brazil, Indonesia and India. These countries, as well as Turkey, are members of the (in)famous “

fragile five” – countries deemed to be the most vulnerable to a slowdown in capital flows to EMs. South Africa, the last member of the gang, was not far behind – right after Hungary and Poland.

The fallout in Turkish assets was exacerbated by

additional factors. For one thing, Turkey had attracted significant capital flows into its government bonds and equities in the last few weeks, some of which exited. Dec. 14’s

police raid on the

Gülenist Zaman newspaper did not help, either. I am sure that economy tsar Ali Babacan would have told President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to wait for a few more days - if his opinion had been sought.

But this past week should have convinced everyone that the oil story will be dominated by the mood toward EMs in the coming months. Therefore, I would not jubilate over the recent respite in Turkish assets. By

ruling out rate hikes “at least [at] the next couple of meetings,” Fed Chairman Janet Yellen managed to calm the markets for now, but turbulence will be back with a vengeance, as uncertainties on the timing of the Fed’s first rate hike reemerge.

You could argue that we should not care much about the volatility in Turkish assets as long as the economy is doing well. However, given Turkish firms’

foreign currency debt and the high pass-through from the exchange rate to inflation, a weakening lira would undoubtedly negatively affect the Turkish economy.

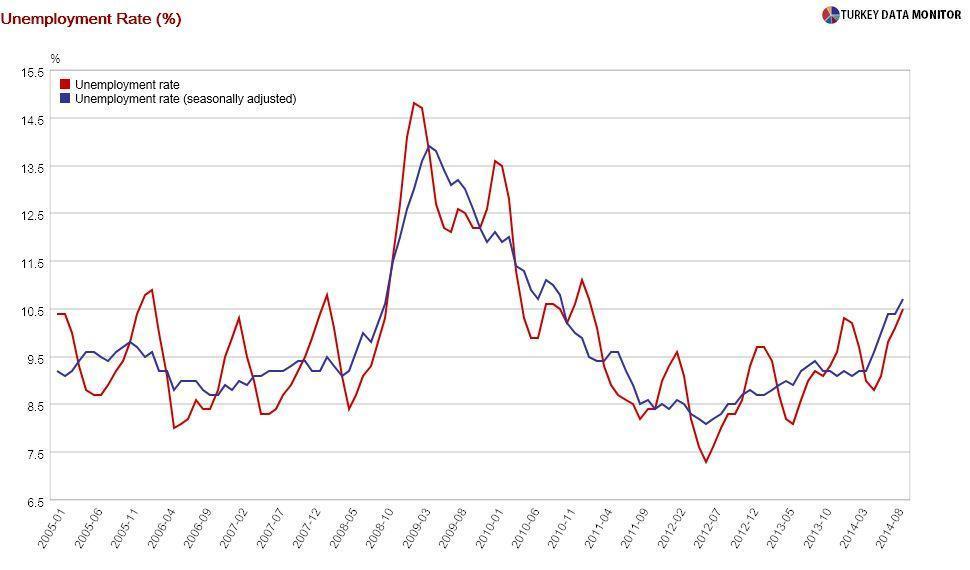

Besides, the Turkish economy is not doing well at all. Latest data corroborate

the story I have been telling in my recent columns: As evidenced by

September labor force statistics released on Dec. 15, the unemployment rate is creeping up because of low growth.

Budget figures released on the same day, on the other hand, are hinting that the government is countering

stalled private investment with public investment, which rose 50 percent annually in real terms in November.

Yellen lent Turkey some more time Dec. 17, but without serious

structural reforms, the country cannot get out of its current low growth predicament. On Dec. 22, I will discuss if the latest set of reforms announced by Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu on Dec. 18 could do the trick.

I looked at emerging market (EM) exchange rates against the dollar on the night of Dec. 17, right before the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) interest rate decision. The Turkish Lira was the second most depreciated currency against the dollar, right after the Russian ruble.

I looked at emerging market (EM) exchange rates against the dollar on the night of Dec. 17, right before the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) interest rate decision. The Turkish Lira was the second most depreciated currency against the dollar, right after the Russian ruble.