Turkish economy heading towards a crisis

A market economist friend lamented to me on March 4 that all she could think about was the exchange rate. She was exhausted from talking to clients on the impact of the lira’s depreciation on the Turkish economy, and claimed that Turkey was heading for a crisis.

Her comments perplexed me, because Economy Minister Nihat Zeybekçi had

noted earlier in the day that there was no reason to worry about the exchange rate. If that is indeed the case, why was Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu in New York,

trying to calm investors, on the same day?

Along with recent remarks from President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s chief economic adviser

Yiğit Bulut that a new paradigm was being defined, Zeybekçi’s comments hint that an orderly lira depreciation is not feared, but actually desired. Could Erdoğan be trying to weaken the lira to make exports competitive?

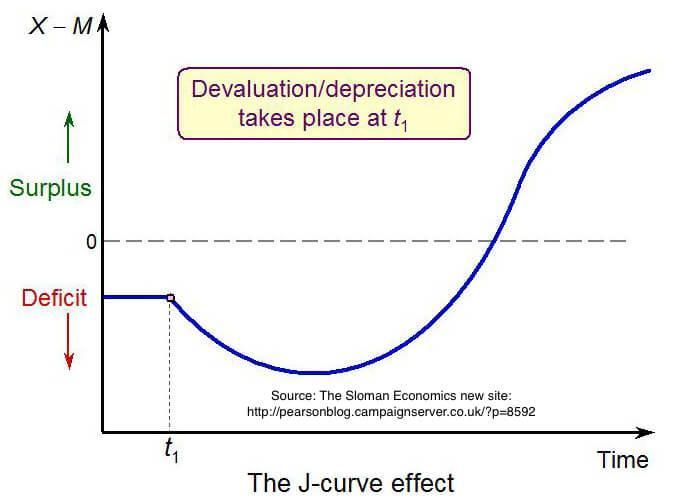

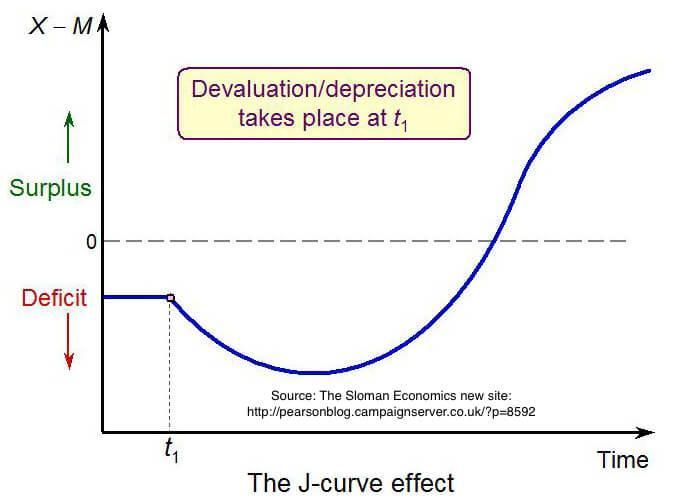

Even in the standard textbook case, a weaker currency would increase a country’s export revenues only after a lag. Lower prices would drive down revenues first. But the increase in exports would eventually dominate the price effect, and revenues would rise. This mechanism is called the “

J-curve.”

Notwithstanding the fact that the relationship does not always hold,

even in developed countries, it is complicated by additional factors in emerging markets (EMs). First of all, since many EMs import quite a lot of inputs as well as consumer products, there is a significant pass-through from depreciation to inflation.

In fact, what really determines the competitiveness of a country’s exports is not the nominal, but

the real exchange rate, which takes into consideration the inflation differential between countries as well. Because of the exchange rate pass-through, Turkey’s real exchange rate depreciation has been much smaller than its nominal one.

The

currency composition and

content of the country’s trade are not working in its favor either. While Turkey receives its export revenues equally in dollars and euros, it pays for almost two-thirds of its import bill in dollars. Its industry is dependent on raw material and intermediate input imports.

That’s not all. Turkish companies hold a significant amount of

foreign currency debt, mostly in dollars.

According to figures released on March 2, the open position of corporates, defined as their net foreign currency (FX) liabilities, jumped from $178 to $183 billion in the last quarter of 2014.

Last but not the least, the lira’s weakness and volatility affect consumer and real sector sentiment.

Consumers simply do not spend, and businesses do not invest when the lira is weakening or jumping around. No wonder that CNBC-e’s preliminary consumer confidence index for February, which was also released on March 2, plunged.

But wasn’t Erdoğan trying to lower interest rates to boost consumption and investment? As I told you in earlier columns, consumption and investment have frozen because of

lack of confidence, not higher rates. His tirades against the Central Bank have weakened the currency, and therefore confidence.

Foreigners have already given up on the lira, as evidenced by the feeble portfolio flows. Even Turks, who usually see a weak lira as an opportunity to sell FX, have started to hoard dollars. It will be very difficult to keep the lira under control in such an environment, and the Central Bank will sooner or later have to hike rates hike

just like in Jan. 2014.

When that happens, all the kudos will go to Erdoğan for having accomplished exactly the opposite of what he was aiming for.

A market economist friend lamented to me on March 4 that all she could think about was the exchange rate. She was exhausted from talking to clients on the impact of the lira’s depreciation on the Turkish economy, and claimed that Turkey was heading for a crisis.

A market economist friend lamented to me on March 4 that all she could think about was the exchange rate. She was exhausted from talking to clients on the impact of the lira’s depreciation on the Turkish economy, and claimed that Turkey was heading for a crisis.