Turkey’s middle income trap

I feel that I sometimes get too occupied with short-term economic matters such as monetary policy at the expense of long-run topics that are much more important. Luckily, Istanbul think-tank Betam usually reminds me of the more vital themes.

I feel that I sometimes get too occupied with short-term economic matters such as monetary policy at the expense of long-run topics that are much more important. Luckily, Istanbul think-tank Betam usually reminds me of the more vital themes.Loyal readers would remember the row between Finance Minister Mehmet Şimşek and Turkish economics professor Dani Rodrik, on how to measure economic growth. While I, and almost all economists for that matter, know that growth should be measured in real terms, the nominal dollars Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita Şimşek is using is still useful for illustrating that Turkey is suffering from the middle income trap.

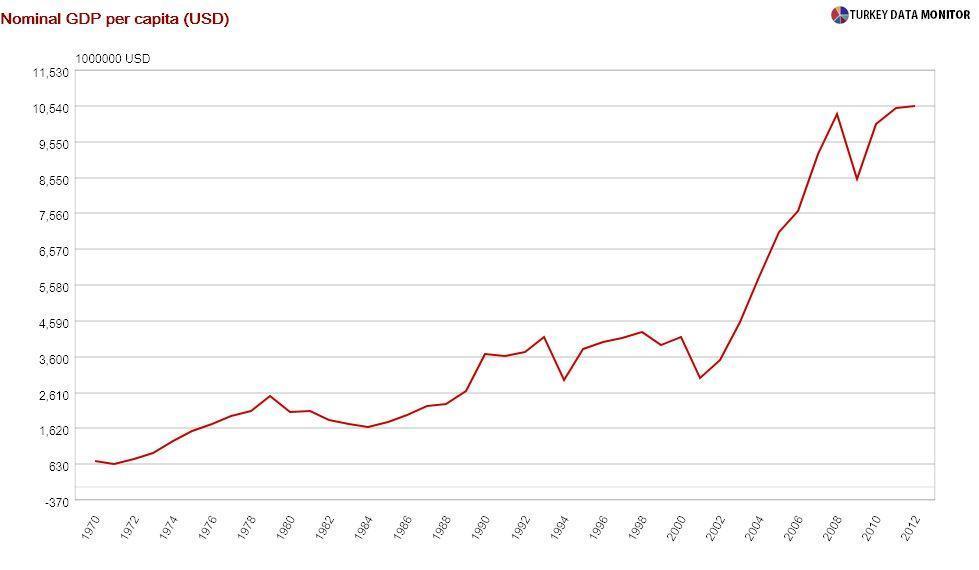

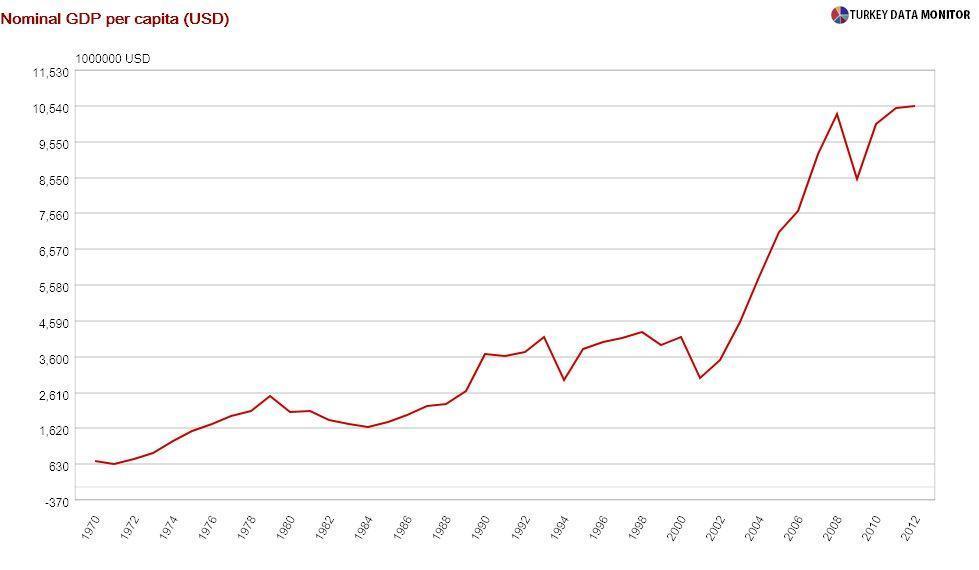

Turkish GDP per capita increased from $716 in 1970 to $4,145 in 2000, which translates to a roughly 6 percent annual growth rate. After plunging to $2,995 in 2001, due to the growth collapse as well as the sharp lira depreciation that year, GDP per capita rose to $3,516 the following year.

The performance in the next decade was impressive. Thanks to decent real growth and an appreciating lira, GDP per capita increased to $10,537 in 2012, allowing Şimşek to boast that they had made Turks three times richer. While this rise corresponds to a very impressive 11.6 percent annual rate, growth from 2002 to 2008 is an even more spectacular 19.6 percent.

However, after rising to $10,315, GDP per capita fell to $8,523 in 2009. It did jump back to $10,000 the following year and has stayed there since. Many developing countries have got stuck at this level, but just the fact that Turkish GDP per capita has been hovering around $10,000 since 2008 does not mean that the country is suffering from the so-called middle income trap. Seyfettin Gürsel and Barış Soybilgen from Betam dig into the data to find out for sure.

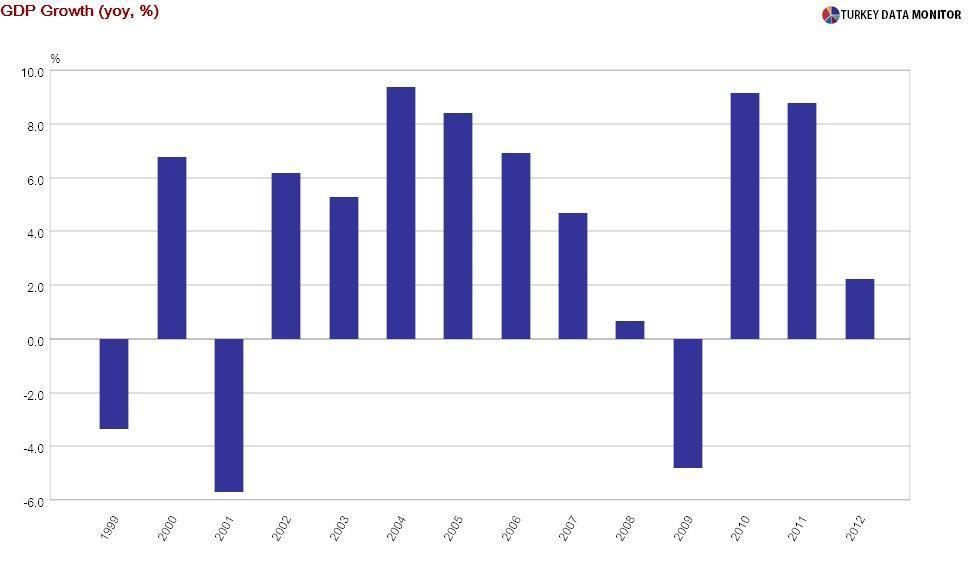

The economists separate GDP per capita growth into employment and productivity gains because they believe that “it is more likely for a country growing on productivity increases to escape from the middle income trap than one where growth is dependent on employment or capital.”

They find that the rise in GDP per capita mainly stemmed from labor productivity and lira appreciation before the 2008 crisis. However, the small increases in GDP per capita since then have mainly been due to employment gains. They note that the contribution of labor productivity was even negative in the last two years.

Gürsel and Soybilgen conclude that without structural reforms that would boost labor productivity, Turkey would get stuck in the middle income trap. The government set a $25,000 GDP per capita target for the centennial of the Republic. They were probably encouraged by the 2002-2008 growth performance. Since we are yet to see any reforms, the next decade is likely to be a carbon copy of the last five years in terms of GDP per capita growth.

I would hope the government officials would act, but Şimşek is probably too worried about Turkey’s national income falling 13 percent since May because of the lira depreciation.