Turkey’s hidden risks in 2013

During

my meetings with investors in London last month, everyone asked whether the country’s large current account deficit could pose a threat next year. Only one person inquired about political risks before I mentioned them.

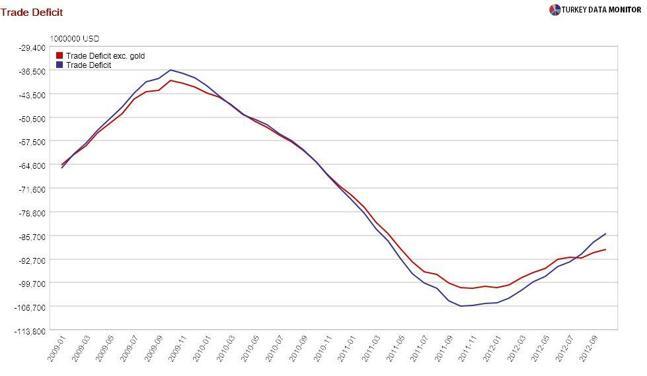

In fact, the latter could affect the former. Economy czar Ali Babacan

recently admitted that Turkey has been de facto running a gold-for-gas program with Iran, which has artificially been improving the current account deficit. Unfortunately, the U.S. Senate is working on a new package of sanctions against Iran, which would end this “game,”

according to a senior Senate aide. If Iran cannot be paid, will it still send gas to Turkey?

What Babacan did not say was that this process is going through state-owned Halkbank. Most of the eye-popping $2 billion foreign flows into equities last week were probably due to the bank’s

successful public offering – which made me wonder just how much profit it has pocketed from the Iran deal. Halkbank and other banks could also be threatened if Turkey fails to tighten laws blocking terrorism finance and

is blacklisted as a result.

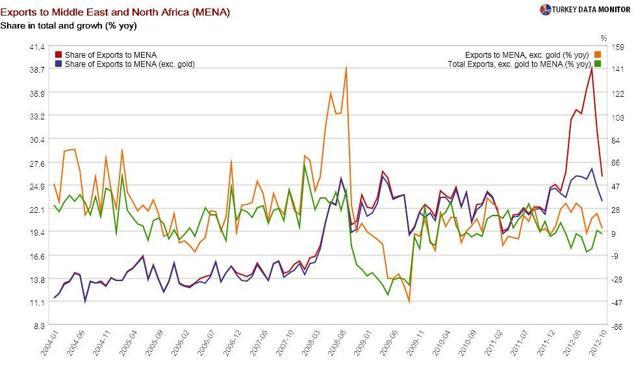

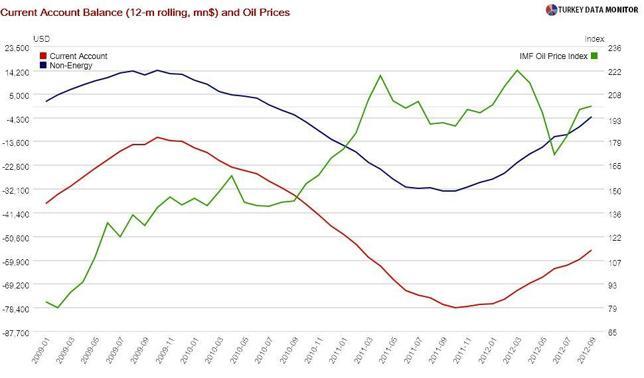

Middle Eastern risks are also overlooked at the moment. While all eyes are on Syria, a conflict between Iraq’s Arabs and Kurds or Iran and Israel could be more harmful for Turkey. For one thing, business relations with the Middle East, which have surged in the last couple of years, would stall. Rising oil prices would increase the current account deficit and inflation.

Domestic political risks are ignored even more. For example, everyone expects a smooth transition from the current president, Abdullah Gül, to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, should the latter wish to ascend to the Presidency. But Gül has been

very critical of the government of late, and may decide to run for the Presidency or try to take the helm of the ruling Justice and Development Party, preventing Erdoğan from placing a puppet in the post of prime minister.

Finally, despite my occasional criticisms of him, I would consider

the possibility of Babacan leaving the government, to be replaced by current Economy Minister Zafer Çağlayan, a serious risk. That could mean a significant shift in economic policy, which would make perennial whiners like me miss the good old days.

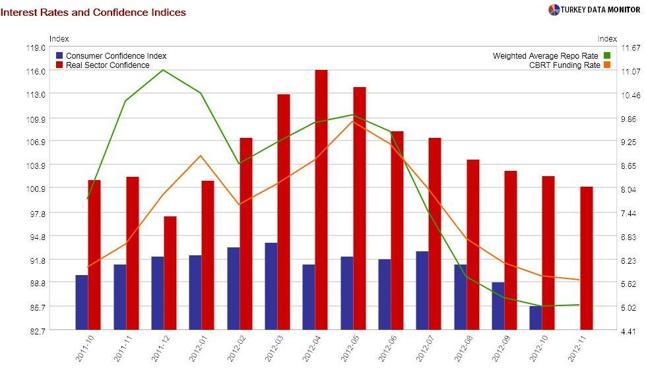

Other than causing selloffs in Turkish assets, these political risks could also disrupt consumer and business confidence, deterring consumption and investment. In fact, GlobalSource analyst

Atilla Yeşilada is arguing this process may have already begun. Although the Central Bank has been cutting interest rates since the summer, confidence indices have been falling.

The ratings agency Fitch upgraded Turkey even though they expect an external financing shock and recession because they believe the country has buffers against a full blown crisis. While

I beg to disagree, I’d be more than happy to give them the benefit of the doubt. However, I am seriously wondering if Turkey has cushions against the political risks as well.

During my meetings with investors in London last month, everyone asked whether the country’s large current account deficit could pose a threat next year. Only one person inquired about political risks before I mentioned them.

During my meetings with investors in London last month, everyone asked whether the country’s large current account deficit could pose a threat next year. Only one person inquired about political risks before I mentioned them.