Turkey’s contribution to the independence of central banks debate

Central bank independence is deeply engraved into the hearts and minds of almost all economists and is one of the must-haves for a sound macroeconomic policy. Or it used to be up until very recently.

Central bank independence is deeply engraved into the hearts and minds of almost all economists and is one of the must-haves for a sound macroeconomic policy. Or it used to be up until very recently.Economist Joseph Stiglitz recently challenged that notion by noting Jan. 3 that “in the crisis, countries with less independent central banks, including China, India and Brazil, did far, far better than countries with more independent central banks like Europe and the United States.” With the Bank of Japan’s independence under threat the issue is now a hot topic.

It is tough to argue with an Economics Nobel Prize laureate, but this observation seems to ignore the fact that the crisis erupted from countries with more independent central banks. But Stiglitz could have added Turkey to his list of successful economies with less independent central banks.

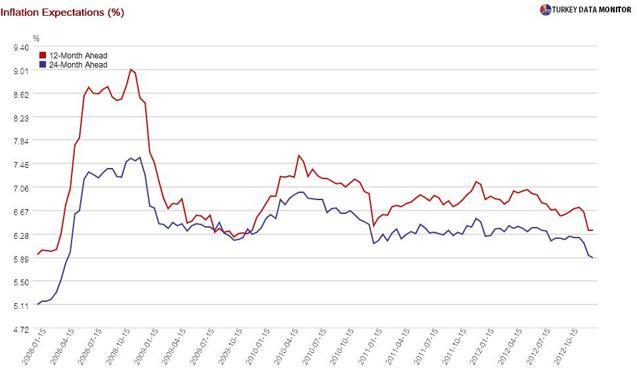

While the Central Bank of Turkey is still independent on paper, markets believe it is accommodating the government’s policies. Inflation expectations have not been responsive to the bank’s inflation targets for the last couple of years and are currently 1.5 percentage points higher than the bank’s end-of-the-year target of 5 percent.

By many accounts, the Turkish economy is doing very well and Governor Erdem Başçı was recently chosen governor of the year by monthly publication, The Banker. But I would argue that economic success should be taken with a grain of salt.

For one thing, as I summarized in my column on Dec. 24, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) argues that the Central Bank’s performance is mixed at best. Moreover, Turkey, with its external finance-led growth model and relatively high interest rates, is one of the countries that are bound to benefit most from the hunt for yield I described in my last column.

In fact, as Murat Üçer of the Turkey Data Monitor recently argued in a panel, strong capital inflows have made it look like the Central Bank is in full control of both interest and exchange rates, which is impossible because of the dilemma of the Impossible Trinity: With free capital flows, you cannot have both a fixed exchange rate and independent monetary policy. I wonder if The Banker considered these before crowning Başçı.

But regardless of Turkey, I think the debate on central bank independence is, to a certain degree, based on the assumption that the central banks have the answers to all economic problems. In reality, central banks have limited tools and monetary policy cannot be used to fine-tune the economy, as the Turkish experience showed.

Moreover, former IMF Chief Economist and University of Chicago Professor Raghuram Rajan noted that, “when central bankers argue that they are the only game on town, they are ensuring that outcome” by relieving pressure off politicians to do the right thing. This is exactly what happened in Turkey.

The debate on central bank independence could benefit from the experience of the Central Bank of Turkey, which is independent and successful on paper, but de facto neither.