Tomaaato, pepper, eggplant

When the November inflation figures came out, I imagined Central Bank Governor Erdem Başçı singing the Barış Manço classic “tomato, pepper, eggplant”.

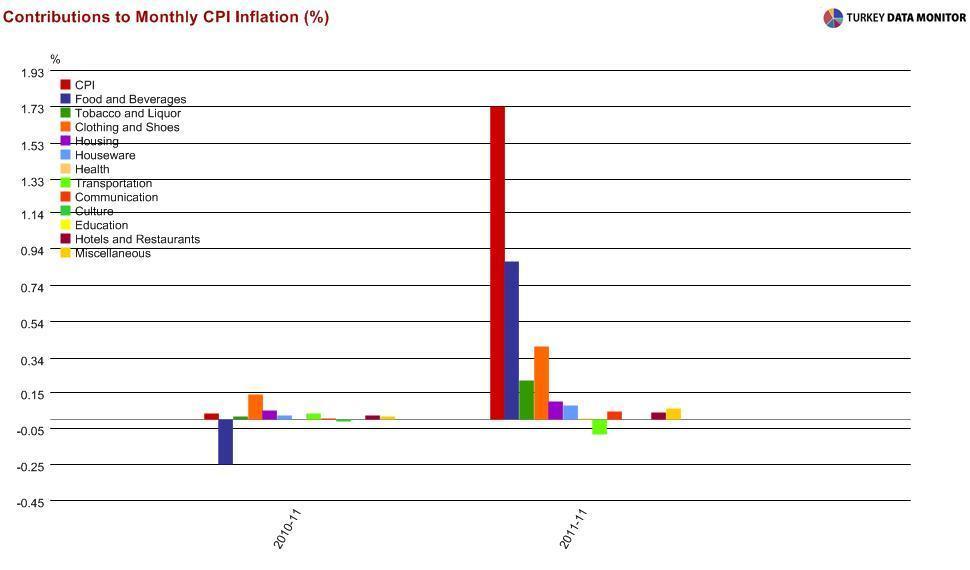

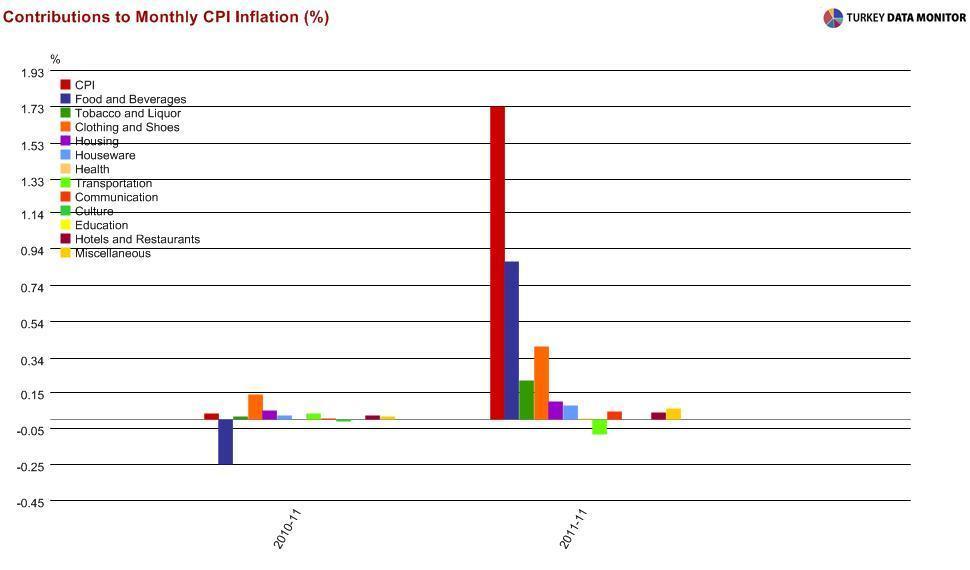

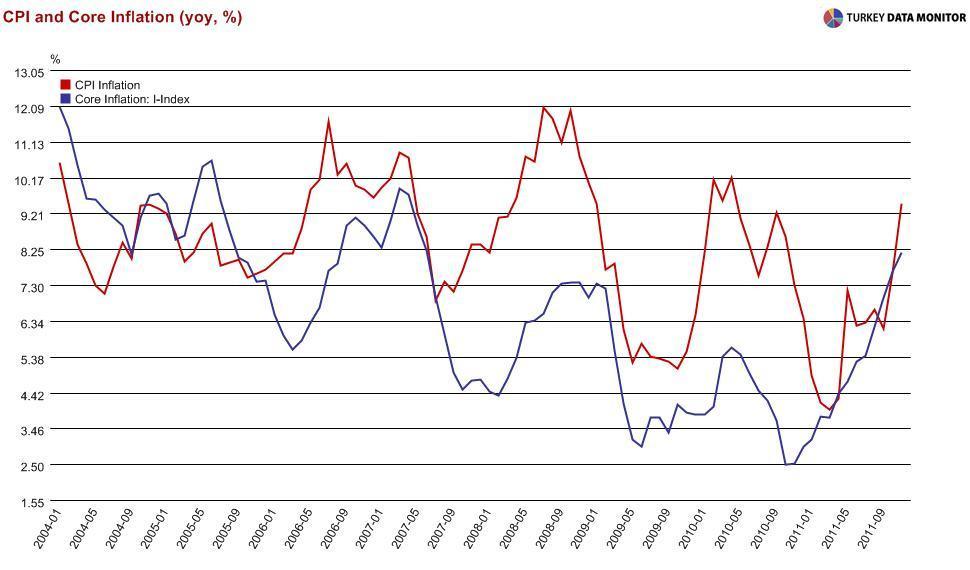

This wasn’t a big surprise, as the Central Bank had warned of a rise in unprocessed food prices, and the Bank blamed it as well as the larger than expected lira depreciation for the increase in inflation. The latter can be seen in the jump in core inflation, which excludes food inflation as well as the recent energy and tobacco administrative price hikes.

Since last December’s inflation was -0.3 percent, we are likely to end the year with a double-digit yearly figure. How about next year? “To convince us that inflation will be falling”, Başçı recently argued that while the policy rate is expansionary, fiscal policy is neutral and both financial sector and liquidity policies are contractionary, making the net policy stance contractionary.

No one believes yearly inflation will be near double-digit territory at the end of next year. If nothing else, “higher inflation this year means lower inflation next year”, as Başçı was “explaining” at the monthly meeting with bank economists last week. But the key question is how far it will fall, and in this respect, Başçı’s arguments do not answer whether the overall policy stance is tight enough for inflation to reach the 5 percent target.

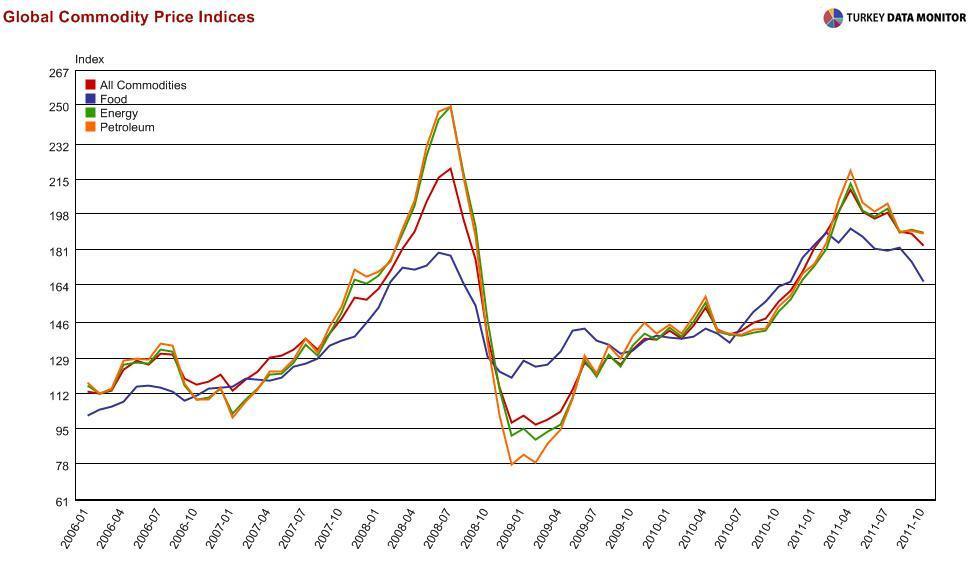

In fact, if you read in between the lines of the Bank’s recent documents, you get a sense that the Bank is well aware of the challenging inflationary outlook. The Bank’s main scenario assumes the continuation of the current monetary policy stance, no further lira depreciation, considerable slowdown in economic activity, limited pricing power by firms that would restrain the second-round effects of an exchange rate pass-through, tame energy and food prices and no major increase in taxes.

Growth is set to decelerate significantly next year, mainly because of Eurozone woes, but believing all these conditions will materialize requires “Pollyannaesque” optimism. For example, the government is projecting an increase of 11.5 percent in tax revenues on the back of 4 percent growth for next year. When it becomes apparent this goal will not be reached because of lower growth, it will be interesting to see whether the government will resort to additional taxes.

More realistically, we should be happy if inflation ends the year near 6.7 percent, the upper end of the Bank’s end-2012 inflation forecast. For one thing, sticky expectations and the persistence of structural inflation paint a difficult picture. Besides, global commodity prices have been favorable this year, but a negative shock can’t be ruled out next year.

Once all my concerns are addressed, I will be a true believer in the Central Bank. Until then, I remain a skeptic.