The expansionary fiscal contraction that worked

Despite the International Monetary Fund/World Bank Spring Meetings, as well as a G20 get-together, the biggest economic news of the past two weeks was the mistake in an influential economic study.

Despite the International Monetary Fund/World Bank Spring Meetings, as well as a G20 get-together, the biggest economic news of the past two weeks was the mistake in an influential economic study.In the paper with the Gabriel García Márquez-inspired title “Growth in a Time of Debt,” Harvard University economists Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff (R2) showed that public debt levels above 90 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) were associated with lower growth.

R2 did not argue for causality. Besides, economic policy should never be shaped by a single paper. Nevertheless, their work was hailed by proponents of fiscal austerity, who have been arguing, with success I should add, that peripheral European countries with high debt need to cut spending. Until someone saw a major flaw in the paper.

University of Massachusetts Amherst economics graduate student Thomas Herndon, working with the data he obtained from Reinhart, noticed that there was a simple mistake in an Excel formula in one of R2’s sheets. Once you corrected this error, R2’s main result did not hold anymore. He turned his findings into a paper with two of his professors, which caused uproar when published last week.

Since I was a research assistant for Jim Tobin, one of the most influential Keynesians of the 20th century, austerity is just not my cup of tea. Besides, there is ample evidence it has not worked in peripheral Europe. However, just to help austerity proponents get back on their feet, I want to offer them probably the most successful expansionary fiscal contraction.

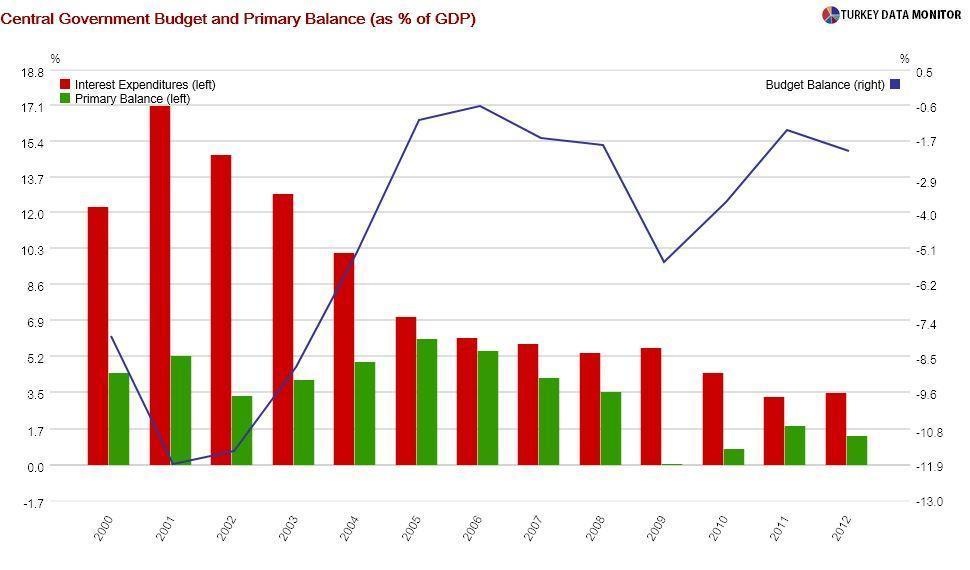

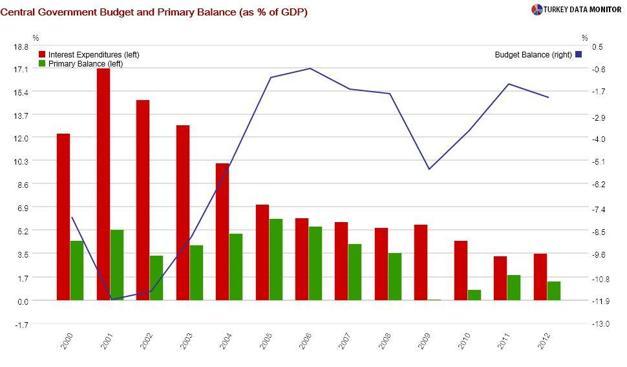

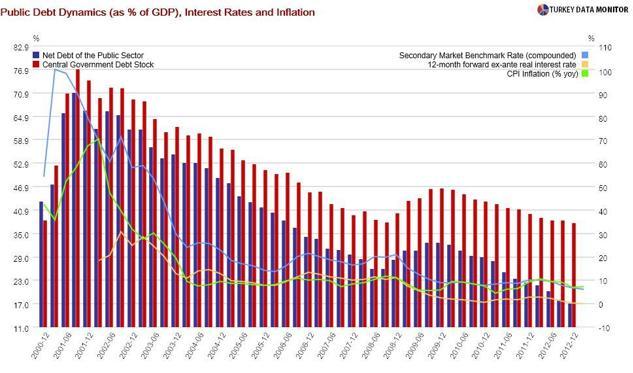

One of the pillars of the Turkish post-crisis recovery program after the 2001 crisis was tight fiscal policy. In a way, this was necessary. Public debt jumped 50 percentage points, from 54 to 104 percent of GDP, when the state cleaned the banking sector, which was both the cause and the victim of the crisis, by recapitalizing state banks and paying the Treasury’s debt to them. There was widespread concern that this rise in debt was unsustainable, and government bond real interest rates were around 30 percent in 2002.

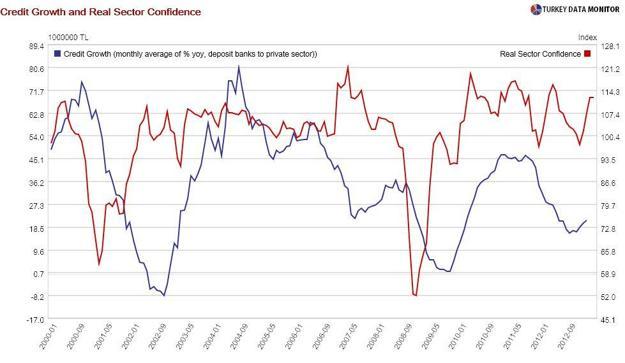

Fiscal consolidation reduced this risk, and with the help of the newly independent Central Bank, inflation and interest rates plunged, reducing interest expenditures and improving banks’ balance sheets. The real sector recovery meant banks’ nonperforming loans fell sharply, and the freshly minted independent banking regulator prioritized strengthening banks’ balance sheets. Banks were ready to lend again, and the rise in confidence meant consumers and businesses to borrow again. The subsequent surge in credit was instrumental in the revival of domestic demand.

When told in this narrative, it seems that the key to the success of Turkish austerity was the improvement in banks’ balance sheets. This was missing from earlier fiscal consolidation attempts of 1994-1995 and 2000. More importantly, it was part of the American response to the global crisis, but conspicuously absent from more recent European efforts.