The economic consequences of #OccupyGezi

The demonstrations caught the Turkish economy at a bad time. There was almost a mini-crisis in emerging markets (EMs), which had already seen the first net outflows in almost a year in the week ending on May 29, last Friday. There were actually sell-offs during the whole month.

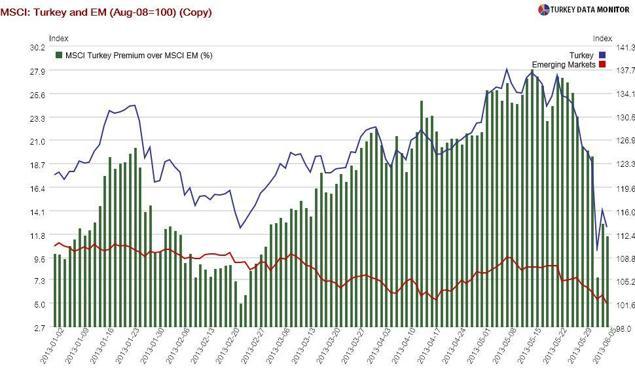

As for Turkey, there were $300 million of outflows last Friday, before the start of the police crackdown, and $1 billion for the whole week. Turkish assets are high-beta, meaning that they do better than other EMs in good times but underperform in bad times. Turkish equities have indeed doing much worse than peers since the third week of May.

It is also important to note that the economy is on a very fragile recovery path, as the

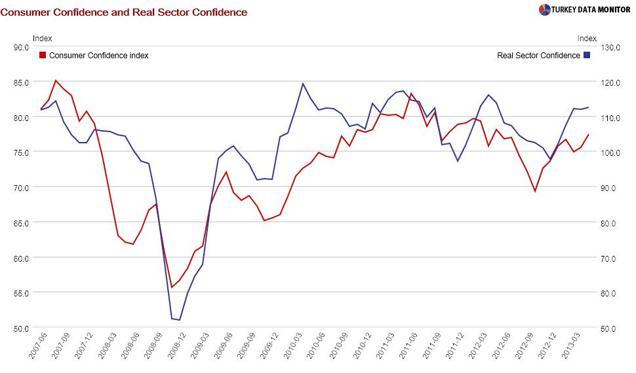

weak May Purchasing Managers Index confirmed. While the overall index fell slightly to 51.1 from 51.3, the exports component hit a six-month low. The pace of recovery is therefore likely to depend on domestic demand, and therefore on consumer and business confidence.

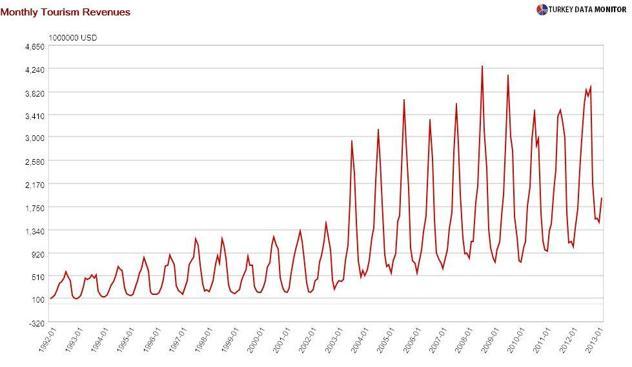

Finally, Turkey earns more than two thirds of its tourism revenues in the five months from the beginning of June to the end of October. Tourism revenues are important because they somewhat alleviate the current account deficit, which is one of the country’s main vulnerabilities.

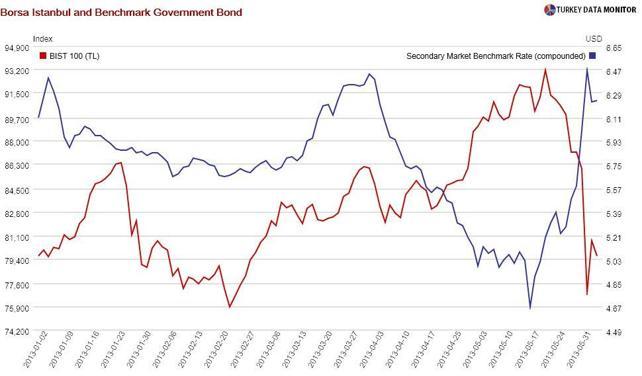

So what fate awaits markets and the economy? Turkish assets were unsurprisingly

hammered on Monday. They did

somewhat stabilize afterwards, but the long-term fate of Turkish assets and the economy is in the hands of Erdoğan. If he adopts a reconciliatory stance after returning from his short North African trip, the country will slowly normalize.

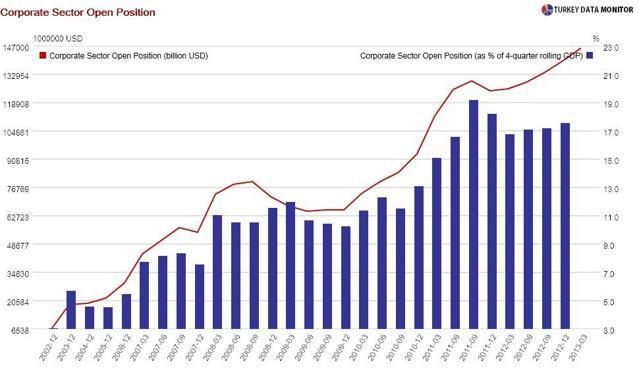

But if he does not step back form the hardline stance he repeated in Tunisia yesterdayand demonstrations go on throughout the summer, the real economy could be affected through the confidence channel, tourism revenues could decline significantly, and there could be heavy capital outflows, depreciating the lira and undermining the balance sheets of the corporates with heavy open foreign currency positions. Erdoğan cannot afford instability before an elections year, and so he would probably resort to pork-barrel spending, undermining the economy’s fundamentals further.

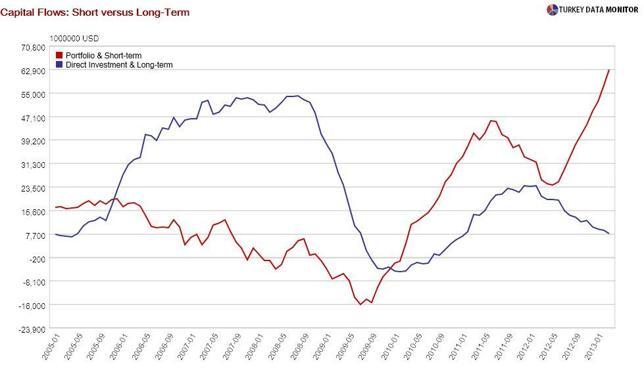

Foreign direct investment (FDI) could be disrupted as well. Turkey’s external financing has been short-term of late, and some FDI would make the country sturdier against a sudden stop of capital flows.

Even if my base case scenario that his advisers eventually put some sense into Erdoğan is realized, the next few months will be anything but rosy because political stability, which had been priced into Turkish assets, is not a given anymore. Turks did not rise against a mall; they were simply fed up with the authoritarianism taking the form of

alcohol bans,

police brutality and the like. And so even if things calm down, I would not be surprised to see similar protests the next time the government tries to enforce its will on the people.

Erdoğan, who happens to be an ex-footballer, has the ball. We will see whether he will kick it out or pass it nicely to the Turkish people.

The demonstrations caught the Turkish economy at a bad time. There was almost a mini-crisis in emerging markets (EMs), which had already seen the first net outflows in almost a year in the week ending on May 29, last Friday. There were actually sell-offs during the whole month.

The demonstrations caught the Turkish economy at a bad time. There was almost a mini-crisis in emerging markets (EMs), which had already seen the first net outflows in almost a year in the week ending on May 29, last Friday. There were actually sell-offs during the whole month.