The Central Bank surrenders without a fight

Just as I was thinking that he had finally stood up to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his cronies blatantly asking for lower interest rates, the Central Bank of Turkey’s Governor Erdem Basçı made a complete U-turn on April 30.

Just as I was thinking that he had finally stood up to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his cronies blatantly asking for lower interest rates, the Central Bank of Turkey’s Governor Erdem Basçı made a complete U-turn on April 30.During the presentation of the Bank’s latest Inflation Report, Basçı signaled that there would be a rate cut soon. He justified lower interest rates by noting that the Turkish Lira had appreciated, volatility had declined, Turkey’s risk premium had improved, and inflation expectations had fallen since the rate hike at the end of January.

I do not deny these facts, although expected inflation is still way too high. However, they are as much due to global developments as the Bank’s rate hike. As Basçı emphasized as well, portfolio flows to emerging markets (EMs) have resumed on the back of the declining uncertainty regarding U.S. monetary policy, the possibility of quantitative easing by the European Central Bank (ECB) and the fiscal performance of EMs with current account deficits.

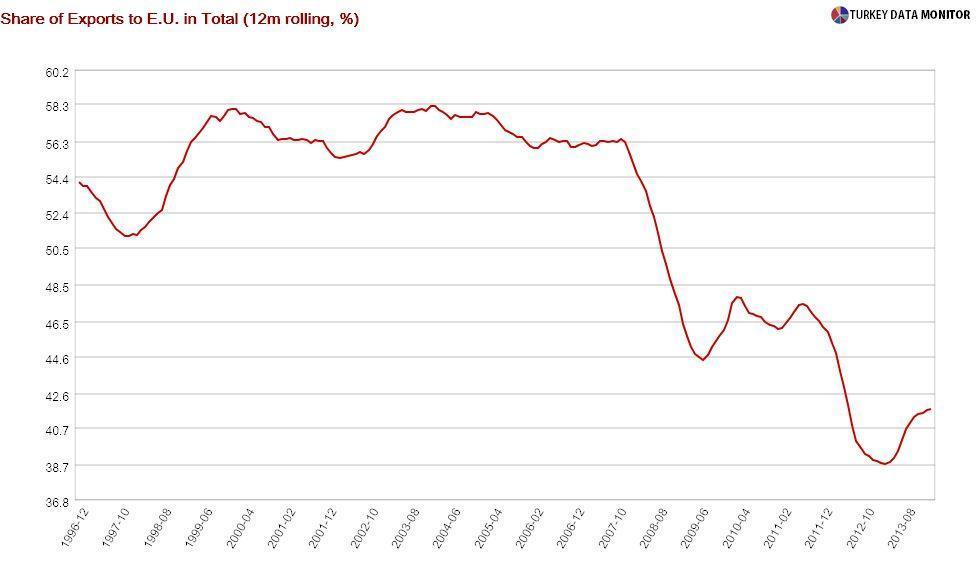

I don’t know about other countries, but Turkey’s March budget figures are screaming pork barrel spending. Besides, we have yet to see how the recent Treasury guarantee on loans for Erdoğan’s mega-projects will be perceived. Besides, ECB President Mario Draghi recently all but ruled out quantitative easing. Notwithstanding the German resistance to such a move, leading indicators such as purchasing managers indices as well as the pickup in Turkish exports to the E.U. are hinting at a recovery.

As for the U.S. Federal Reserve, I got interesting comments from the economists I met during my trip to Washington, D.C. to bid farewell to my friend Esther. First of all, almost all claimed that the economic recovery was on track, despite Wednesday’s weak first quarter growth turnout. More importantly, some argued that potential growth had fallen, causing the non-inflationary unemployment rate to rise. As a result, wage inflation could emerge, forcing the Fed to raise rates sooner than expected.

I honestly don’t know the U.S. economy well enough to evaluate these claims, but I have read recent reports and papers supporting them. In any case, if markets buy this argument, Turkey could be adversely affected once again. A rate cut by the Central Bank of Turkey would prove to be premature then, reviving depreciation pressures on the lira and risking a sudden stop of capital flows.

I won’t even get into the awkwardness of Basçı bringing up rate cuts right after announcing an upward revision to the Bank’s end-year inflation forecast. My only solace is that he also signaled that cuts would be gradual: The Bank would lower rates moderately once and then wait to see the impact of its move before undertaking further cuts.

I am worried that even a single unluckily-timed cut could do a lot of damage, as we experienced firsthand in the summer of 2011 - when the Bank lowered rates right before the European meltdown, only to raise them sharply in October. We’ll see if history repeats itself soon.