The Bankers’ New Clothes

As he acknowledged when literally taking the stage to deliver the keynote address at the gala dinner of the Central Bank of Turkey’s “

Global Finance in Transition” conference on May 7,

Martin Hellwig had a tough act to follow. The talented

Karsu Dönmez had just delivered an amazing mini-concert.

The Max Planck Institute professor was able to follow in Dönmez’s steps, so much so that I downloaded

“The Bankers’ New Clothes,” his recent book with Stanford University professor

Anat Admati, to my Kindle right after I got back home. I finally managed to read it this past week.

The book’s subtitle explains what it is about: “What’s wrong with banking and what to do about it.” Simply put, according to the authors, the major problem with banking is its dependence on debt rather than equity, and the main fix is to force banks to hold more capital, which they are vehemently opposed to.

I’ve read almost all the major books on the financial crisis, and what makes this one of the best, if not the very best, is its simplicity and accessibility. I myself used to think that banking was a complicated trade. Admati and Hellwig explain how it is basically no different from any other business, by introducing us to imaginary house buyer Kate, whose misadventures we follow throughout the book.

When Kate buys a home, her deposit is a like a bank’s capital. If Kate puts down a deposit of 5 percent and borrows the rest, she triples her money if her house increases in value by 10 percent. But if its falls in value by 5 percent, she loses everything. If Kate puts down a larger deposit, she will make a smaller return if prices rise, but is less likely to lose it all if they fall.

Banks usually don’t lose much during a downfall, as they are “too big to fail” and bailed out by the government. If you would like to know how this works, I could recommend Andrew Ross Sorkin’s

book of the same name, or if you are a more visual person, the

star-studded movie adapted from his book.

It is therefore not a big surprise that bankers don’t want to hold more capital, and they have come up with ridiculous arguments, which Admati and Hellwig rip apart in a way non-economists can easily follow. For example, their explanation of the famous

Modigliani-Miller theorem, which they use to show that too much equity does not mean banks will lend less at higher rates, is remarkable.

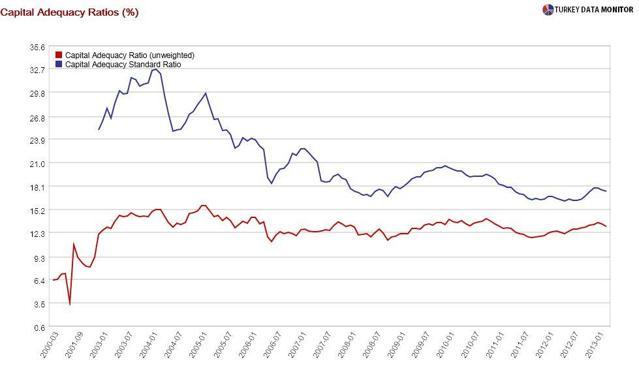

I did not have a chance to ask him after his speech, but I am sure Hellwig was very glad to be in Turkey. After all, while not at the 20 percent level he and Admati are asking for, Turkish banks’

capital adequacy ratio, which is the ratio of their shareholders’ equity to assets, is 17 percent - or 13 percent if not weighted by the risk of assets.

The country’s robust banking system and tight regulation are results of

the recovery program after the 2001 crisis, which prioritized cleaning up the banking sector and strengthening banks’ balance sheets. As I often say, the crisis was probably the best thing that happened to Turkey.

As he acknowledged when literally taking the stage to deliver the keynote address at the gala dinner of the Central Bank of Turkey’s “Global Finance in Transition” conference on May 7, Martin Hellwig had a tough act to follow. The talented Karsu Dönmez had just delivered an amazing mini-concert.

As he acknowledged when literally taking the stage to deliver the keynote address at the gala dinner of the Central Bank of Turkey’s “Global Finance in Transition” conference on May 7, Martin Hellwig had a tough act to follow. The talented Karsu Dönmez had just delivered an amazing mini-concert.