'Tekıling törkiyz ecukeyşınıl vooz'

Turkey’s National Education Council, an educational advisory body, decided over the weekend before last to recommend the Ministry of Education that Ottoman-language classes should be compulsory for religious high schools and electives for others.

Turkey’s National Education Council, an educational advisory body, decided over the weekend before last to recommend the Ministry of Education that Ottoman-language classes should be compulsory for religious high schools and electives for others.Having read dozens of columns and watched endless debates, I still do not know what supporters of the recommendation, including President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, actually mean by Ottoman. One can learn to read enough Arabic characters to be able to read books published in the Ottoman Empire a century ago in a couple of weeks, as two friends have done. It would take years to learn the official written communication of the empire.

I could also argue, as Financial Times’ Daniel Dombey and others have done, that this latest tirade is part of a bigger theme: Erdoğan is looking to the classroom to create a religious generation. After all, another Council recommendation was the introduction of religious education for six-year-olds, which was also backed by him.

I won’t bother. Not because less than 10 percent of Turkish students attend religious schools. And not because Dombey is probably part of the international masterminds trying to wreck Turkey, to whom Erdoğan referred to on Dec. 12. I simply believe that this whole debate is preventing us from tackling Turkey’s educational woes.

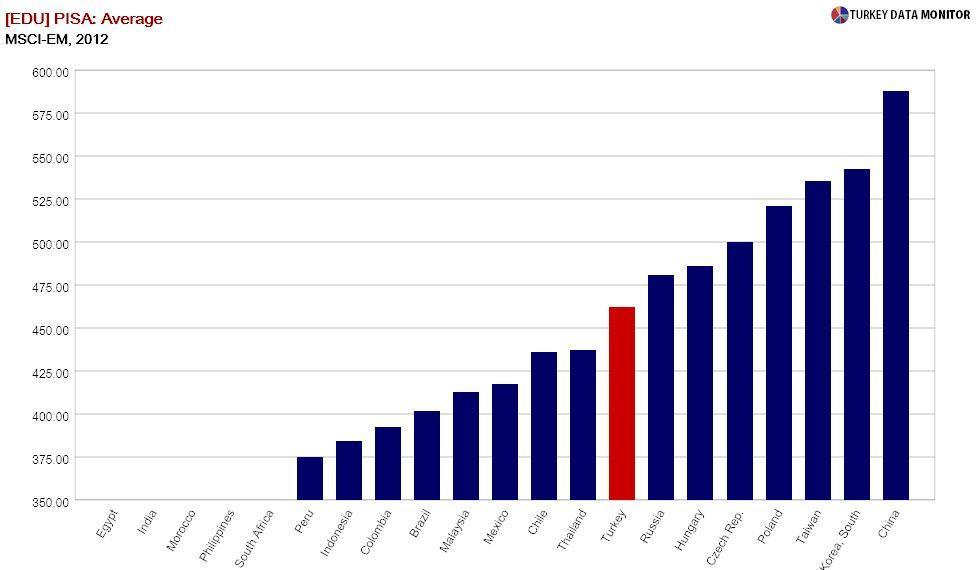

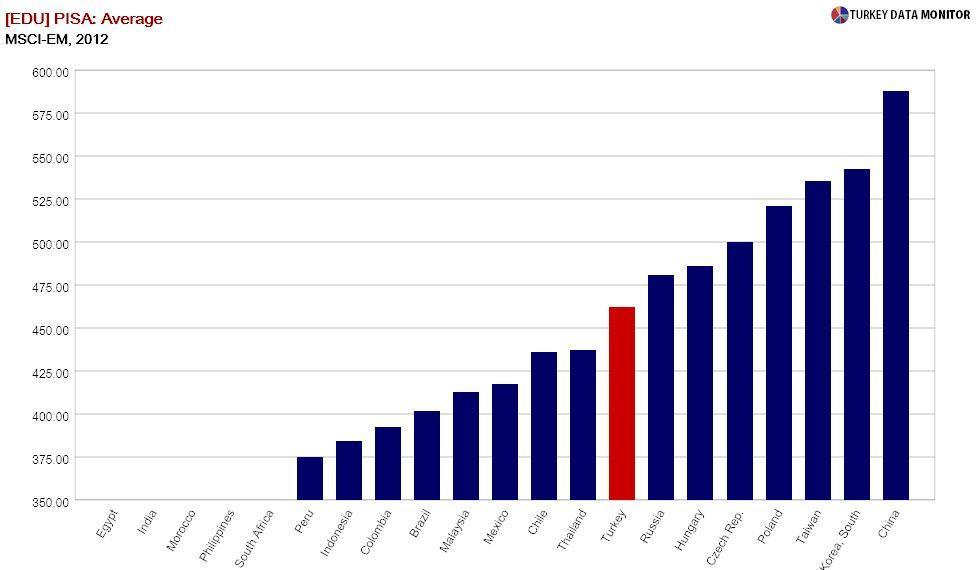

Academic studies have found that Turkey’s growth is held back by low productivity more than anything else, with human capital being the binding constraint on productivity. While Turkish students’ scores in international PISA tests have improved in the last decade, they are still lower than peers’ in countries with similar GDPs.

The most striking result of these tests is the huge inequality in Turkish students’ performance. For example, the best score higher than the best students in Singapore, the country with the highest marks, in the similar TIMMS exam, while the worst score lower than the worst students in Morocco and Ghana, which sit at the bottom of the rankings.

And if Erdoğan really wants Turkish students to learn a language, he could try English. Turkey is ranked 47th out of 63 countries international education company EF Education First’s English Proficiency Index, the lowest-ranked country in Europe and classified as “very low proficiency.” TOEFL scores tell a similar story.

The EF emphasized that Turkey’s proficiency score rose more than any country in Europe during the last seven years, but the picture remains bleak. A recent report by Ankara think tank TEPAV and British Council found that despite able teachers, Turkish kids cannot learn English in high school. They won’t be able to in college, either: A clause squeezed into a recent law prohibits university programs in Turkish from making foreign language classes obligatory.

“Whether they want it or not, Ottoman will be learned and taught in this country,” Erdoğan vowed on Dec. 8. I wish he would show the same zeal for making Turkish children proficient in English. Then, we would not have ministers reading English the way I wrote the title of the column.