Social Implications of Turkish Reforms

I was in Baku April 8-10. Followers of our editor-in-chief Murat Yetkin’s columns may have thought I was at the regional World Economic Forum (WEF) as

a guest of Azeri state oil firm SOCAR as well.

I was actually at the Hilton where the WEF conference was being held, but for a different reason. I was at the more modest “

Policy Options for Social Market Economy: National and International Perspectives” conference, as a guest of the German

Konrad Adenauer Foundation.This was probably better, as I wasn’t too pleased to see the nation’s oil wealth channeled into

white elephants designed to impress foreigners. I will summarize the conference, the Azeri economy and my impressions of Baku in the next two columns, but for now, I would like to recap my presentation titled “Turkish Reforms and Their Social Implications”.

I discussed the

reforms of the late Turgut Özal as well, but there is hardly data to measure the social impact of the 1980s’ economic transformation, so I had to concentrate on the measures after the 2001 crisis.

The key to the

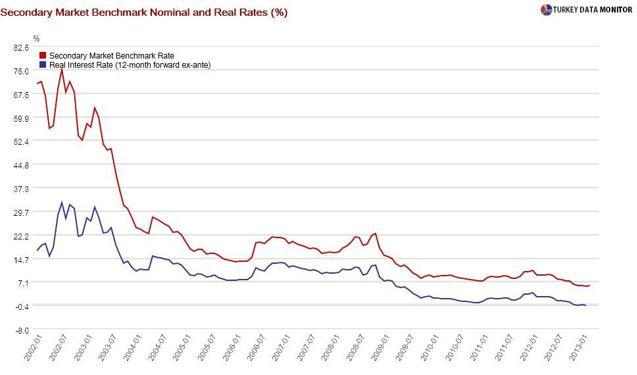

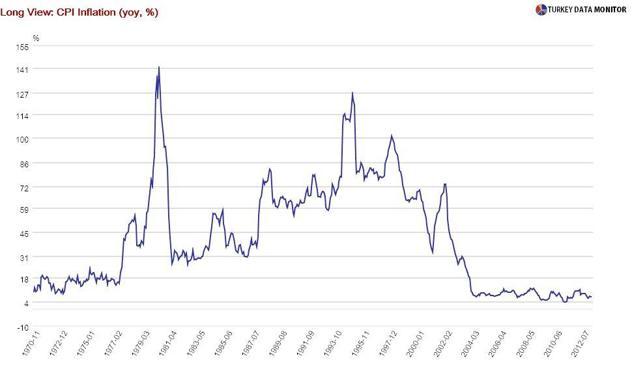

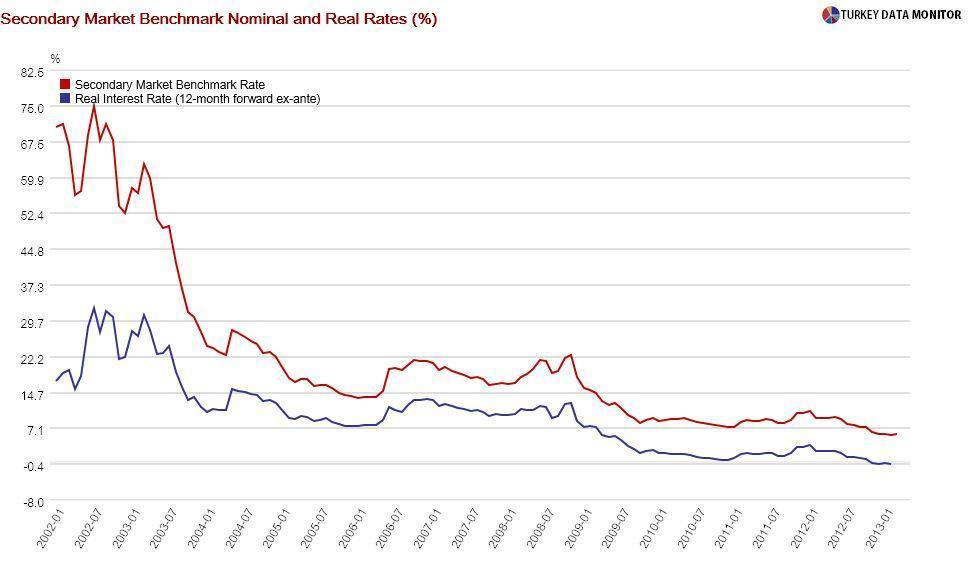

Turkish post-crisis recovery program was an expansionary fiscal contraction, which enabled interest rates to fall rapidly. Giving the Central Bank its independence and implicit inflation targeting managed to pull inflation down to single digits. A banking system overhaul and independent regulator ensured that Turkish banks were immune from the 2008-2009 global crisis.

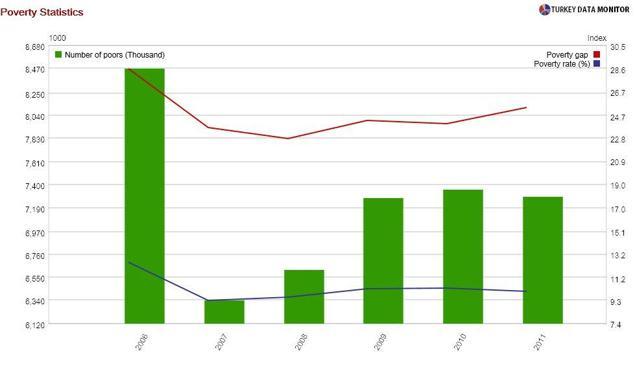

In sum, Turkey managed to achieve macroeconomic stability, which has made it the darling of foreign investors. But how did this economic strength affect the average Turk and especially the poor? Poverty did indeed fall sharply in the early years of the AKP, but then rose in 2007-2008. It has more or less stayed constant since then.

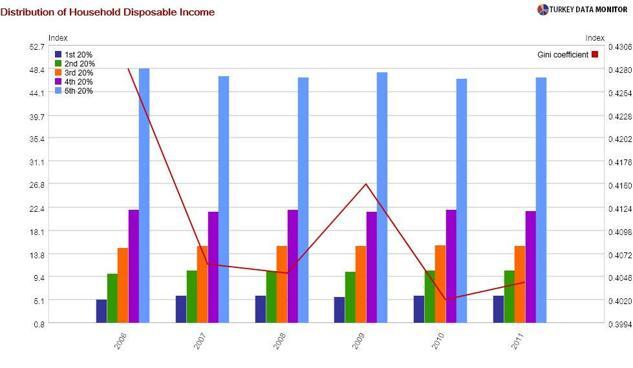

Similarly, inequality has followed a “wavy” path during the last decade. The 2001 Turkish and 2008-2009 global crises render an objective evaluation of the AKP’s “social performance” nearly impossible. However, a look at the distribution of household after-tax income reveals interesting results.

The richest 40 percent of Turkish households have seen their share in total income fall since 2006. And while the poorest 20 percent have increased their share a bit, the largest gains have been made by the next 40 percent. In sum, it has been the middle classes that have benefited the most from Turkish reforms. Driving in Istanbul’s booming neighborhoods such as

Güngoren and Ümraniye, which are unsurprisingly bastions of the AKP, would confirm this result.

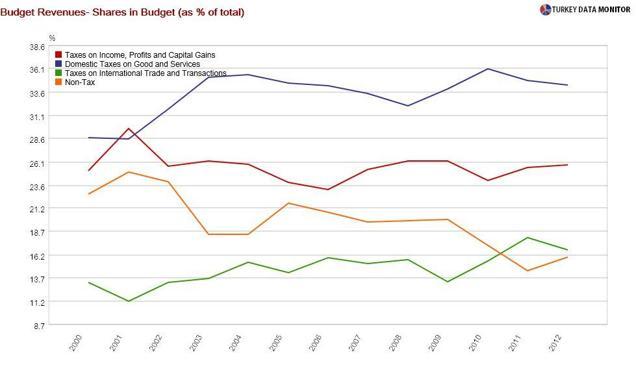

While I don’t have access to any data, the middle classes’ share of consumption and wealth may have increased more than income. The low interest rates have enabled many to buy a home or car for the first time. Turkey’s dependence on indirect taxes limits their consumption power a bit, but many of these nouveaux bourgeois don’t pay taxes anyway, especially if they have their own business.

In case you were wondering why the AKP has constantly been getting half of the votes despite a decade in power.

I was in Baku April 8-10. Followers of our editor-in-chief Murat Yetkin’s columns may have thought I was at the regional World Economic Forum (WEF) as a guest of Azeri state oil firm SOCAR as well.

I was in Baku April 8-10. Followers of our editor-in-chief Murat Yetkin’s columns may have thought I was at the regional World Economic Forum (WEF) as a guest of Azeri state oil firm SOCAR as well.