Six puzzles of the Turkish economy

I have been burning a lot of brain cells of late on six puzzles of the Turkish economy. I have already made some way into solving some of them, while I am still baffled by others. I will simply state them today, with the hope of sharing my answers over the course of the next few weeks.

I have been burning a lot of brain cells of late on six puzzles of the Turkish economy. I have already made some way into solving some of them, while I am still baffled by others. I will simply state them today, with the hope of sharing my answers over the course of the next few weeks.A significant part of Turkey’s large current account deficit has been financed by net errors and omissions (NEOs), which is basically an accounting term covering everything in the Balance of Payments that is not measured. This item amounted to $2 billion in July (that figure was later revised down to $1.6 billion), prompting many to speculate on the sources of these funds. What exactly are NEOs?

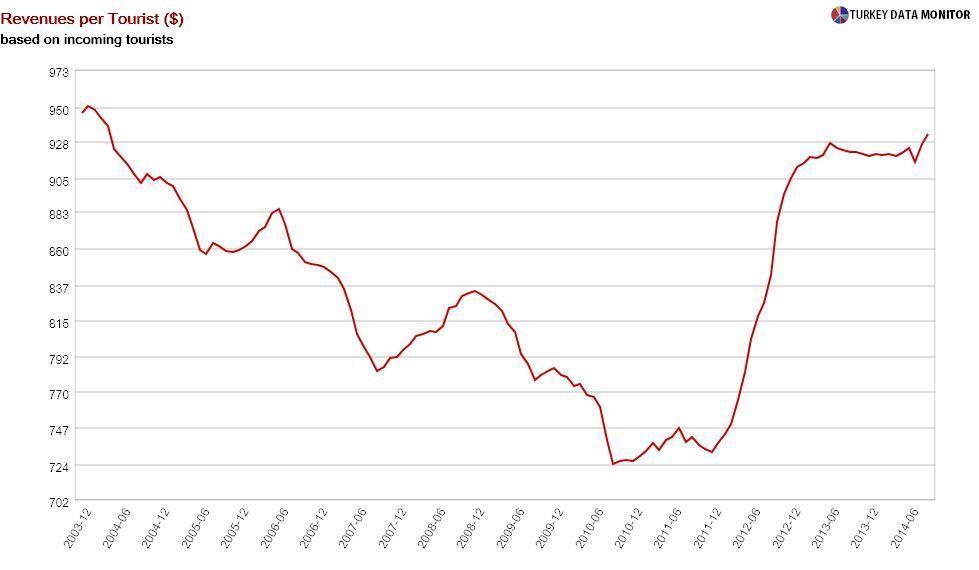

Although Turkey recently overtook Great Britain to become the world’s sixth top tourism destination in terms of international arrivals, the country is 12th in terms of revenues earned from tourism, because revenues per tourist are low. But after having fallen consistently for a decade, they surged in 2012, and by the end of the year, they were near their levels in 2004. What happened?

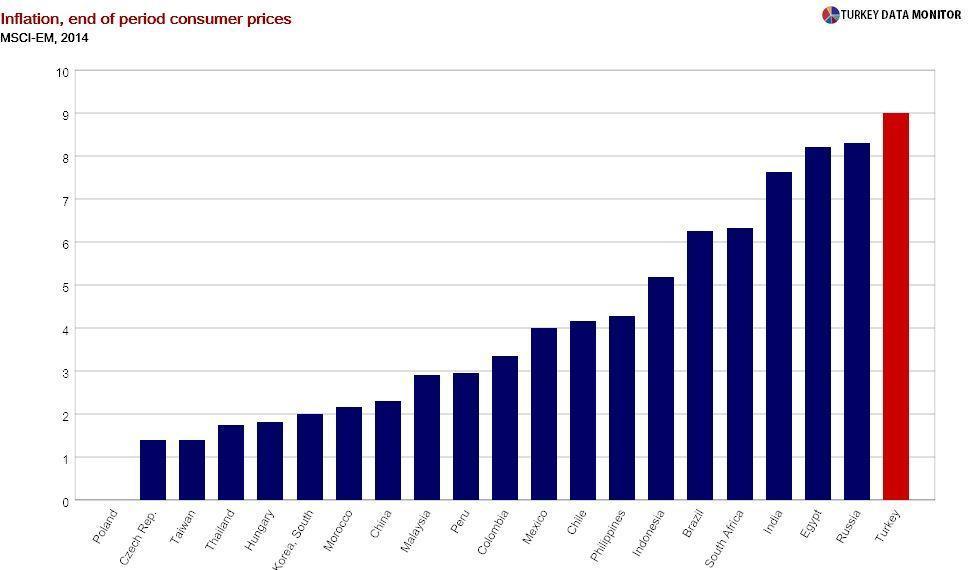

Many countries in the world are fighting deflation. On the other hand, although it will be falling over the course of the next few months, Turkish inflation is still high, in fact among the highest in the world. Why are price developments in Turkey so decoupled from those in other countries, even emerging markets similar to Turkey?

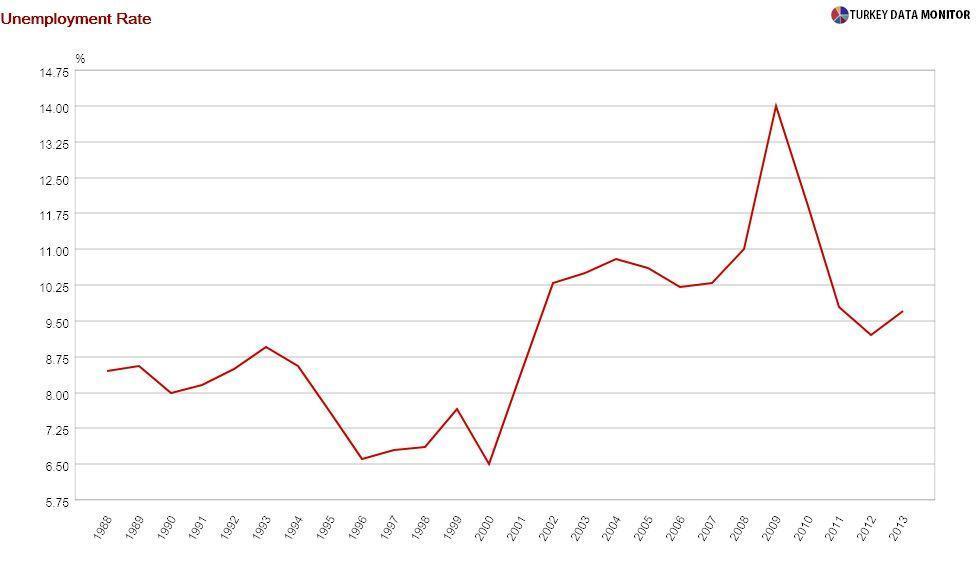

There are several B-level mysteries of the Turkish labor market, such as the recent rise in women’s labor force participation and employment-generating growth, which I explain below. I have some potential answers for those. However, I cannot really explain the rise in unemployment over the last three decades. The unemployment rate seems to have settled to a higher plateau of 10 percent, from 7-8 percent in the late 1980s and 90s. Why did this happen?

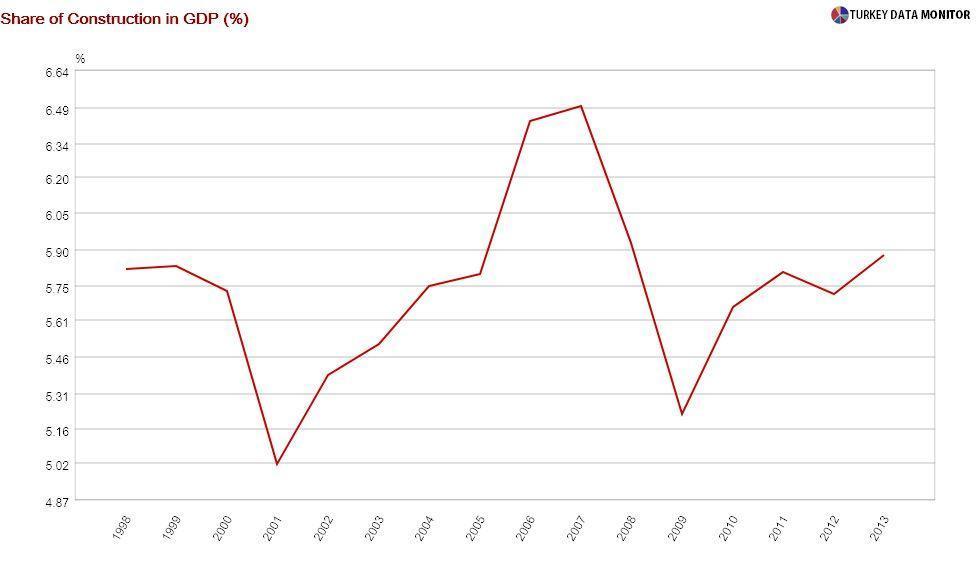

Many Turkey economists have emphasized the rising prevalence of the construction sector in the Turkish economy. This fact is not only supported by statistics, such as building and occupancy permits and home sales, but could be confirmed by even a first-time visitor to Istanbul, who is bound to notice the cranes sprouting from all around the city like mushrooms. However, the share of construction in GDP has been hovering around 6 percent since 1998. What is going on?

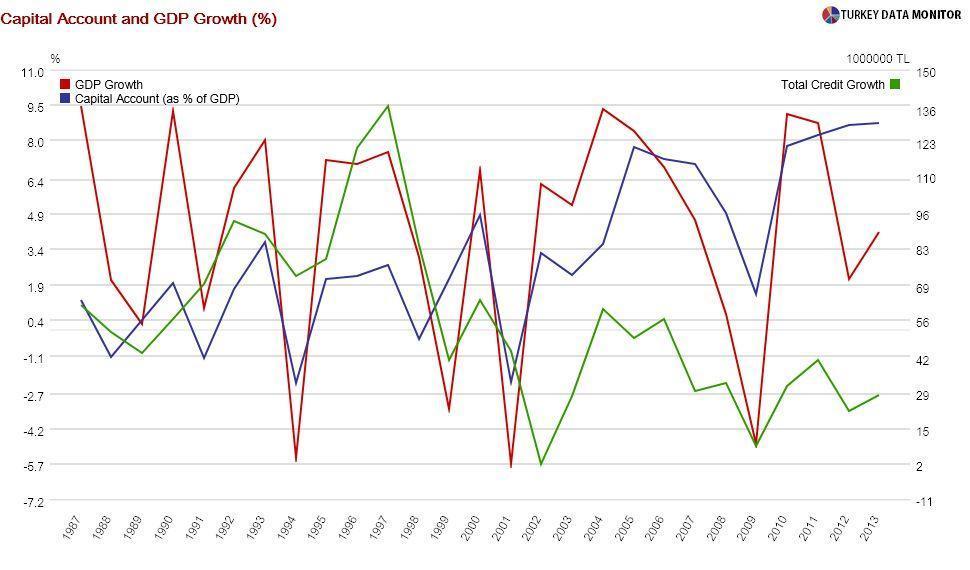

Speaking of growth, I have a couple of related mini-puzzles. Turkey’s growth model is based on channeling external financing to credit and consumption. Why has this link somewhat weakened over the last couple of years? Perhaps linked to this observation (perhaps not), why has growth been more employment-generating than before, roughly during this same period?

Unless there are important economic developments that need to be addressed immediately, I will tackle the NEOs and tourism revenues in the next two columns. I am quite confident with my answers to those two, while I still need to do some work to get satisfactory solutions to the inflation, employment, construction and growth puzzles.