Rigging in Ankara? A few election observations

I celebrated Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s local elections victory with a Jordanian friend in Cape Town’s Waterfront Sunday night- by drowning my sorrows in South African wine.

I think I was being a bit sentimental. First of all, was that really a victory? As I explained in

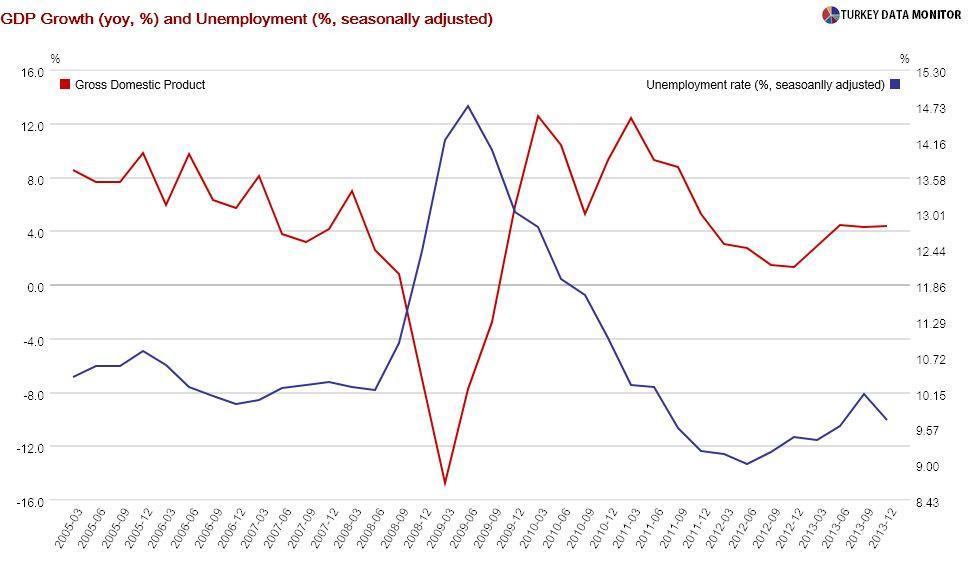

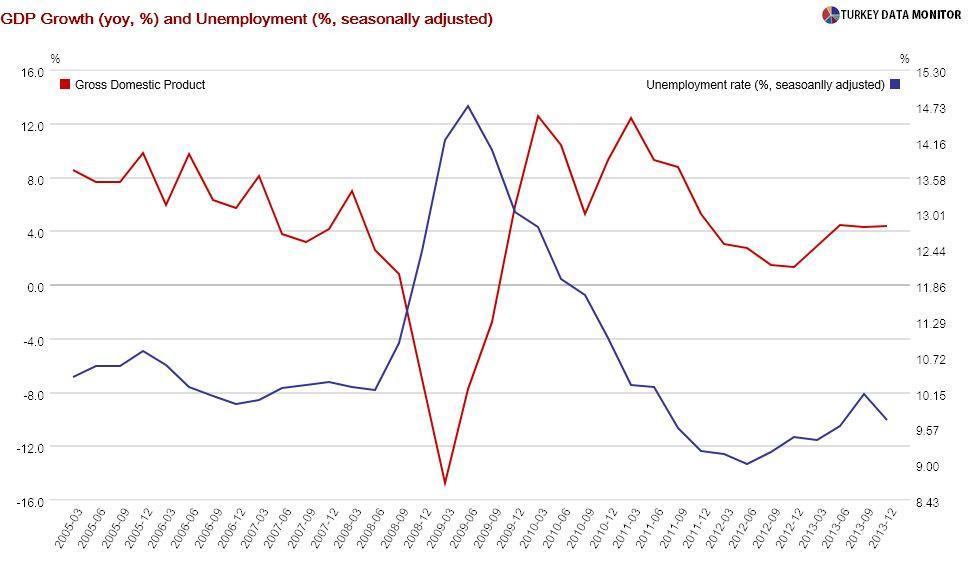

my Jan. 3 column, voters do not punish corruption in countries where corruption is prevalent as long as the economy is doing well. Although I expect a significant slowdown in the second half of the year, the Turkish economy

managed to hold up until the local elections.

In a similar manner, it is not correct to compare Sunday’s results with those in the previous local elections in March 2009. Growth had bottomed out and unemployment peaked right at that time, and so it wasn’t such a surprise that the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP’s) votes fell below 40 percent without any graft scandal.

And using the same logic, unlike what many are claiming, the local elections were not a defeat for the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP). After all, with the exception of the 1977 general and local elections, when it was led by the legendary Bülent Ecevit, the CHP has never been able to get more than 30-33 percent of the votes.

This is as much due to Turkish voters’ preferences as the CHP’s incompetence, the main reason for its supposed failure according to the disgruntled Turks around me. Most Turkish citizens want a conservative party that will make them richer, and the AKP has been able to deliver it for them, though mainly due to global conditions and in a

completely unsustainable manner.

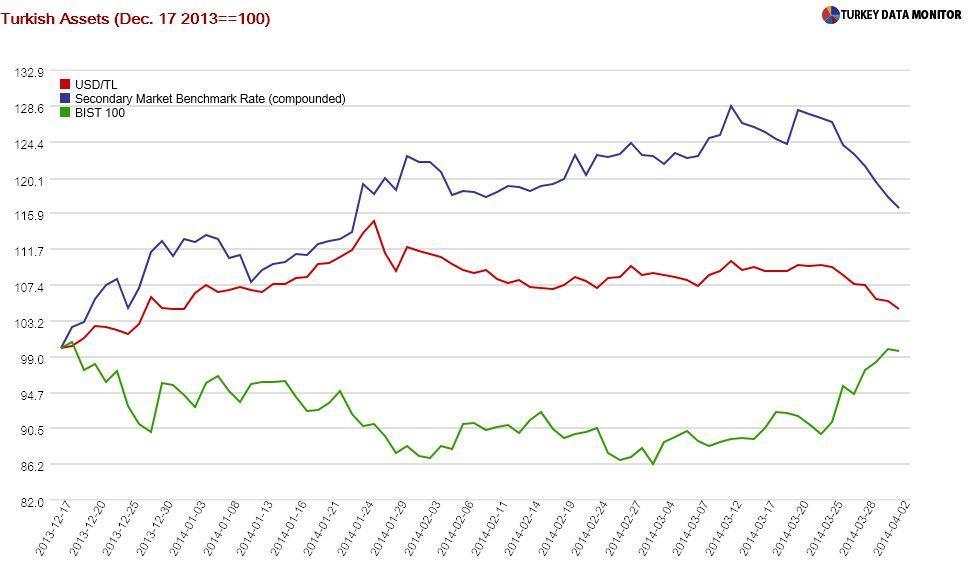

The

rally in Turkish assets this week should not be a big surprise, either. It reflected better-than-expected data and positive global developments as much as the election results. But as I explained in

my March 28 column, markets are wrongly assuming political stability has been delivered to Turkey from now on. In fact, I am confident two of these three factors will disappear soon.

Last but not the least, Swedish economist Erik Meyersson

looked at the relationship between the voter turnout, share of the ballot boxes declared as invalid and votes for the AKP/CHP. He found the AKP did better in ballot boxes with more than a 100 percent turnout. However, this could be due to factors other than rigging, such as the small size of these boxes.

Erik also found a positive relationship between the share of invalid votes in ballot boxes and the difference in votes between the AKP and CHP. However, his analysis also suggests there may be some factors he is not measuring that could be accountable for invalid votes. Indeed, another study established that districts with a high share of invalid votes have voters with lower education.

The data does not support that

the cat(s) that caused electricity blackouts by

entering power distribution units in Ankara had almond moustaches for whiskers, but the fact that more than 20 provinces were affected

cannot just be coincidence. And please #RememberBerkin.

I celebrated Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s local elections victory with a Jordanian friend in Cape Town’s Waterfront Sunday night- by drowning my sorrows in South African wine.

I celebrated Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s local elections victory with a Jordanian friend in Cape Town’s Waterfront Sunday night- by drowning my sorrows in South African wine.