Quantitative easing III: Boon or bane for Turkey?

It has been exactly two months since the Federal Reserve (Fed) announced its third round of quantitative easing, dubbed QE3.

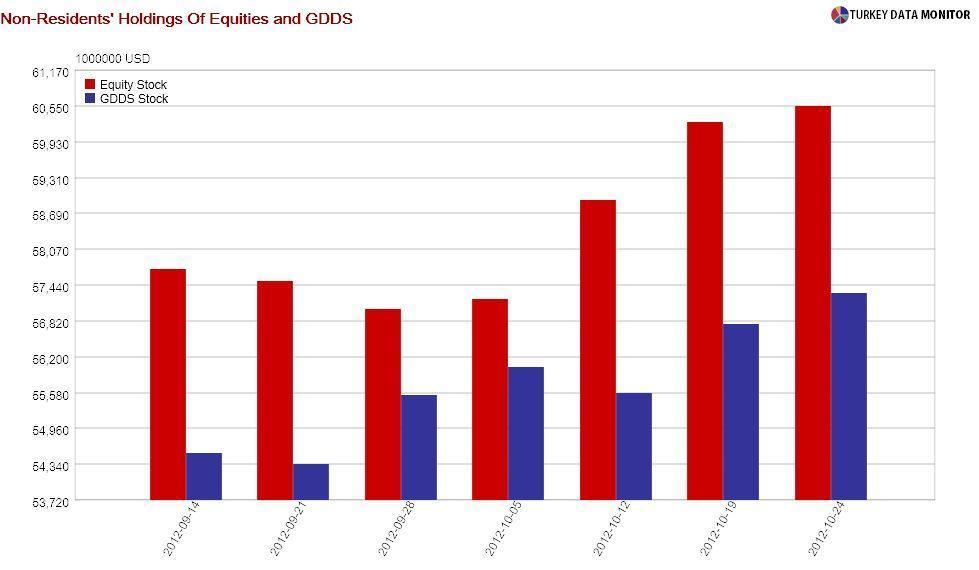

Under the program, the Fed has agreed to purchase $40 billion a month in mortgage-backed securities while pledging to keep policy rates extremely low until at least mid-2015. I would argue that the very strong flows to emerging markets since then are due to the latter, as the ultra-low interest rates for the foreseeable future have investors chasing yields elsewhere.

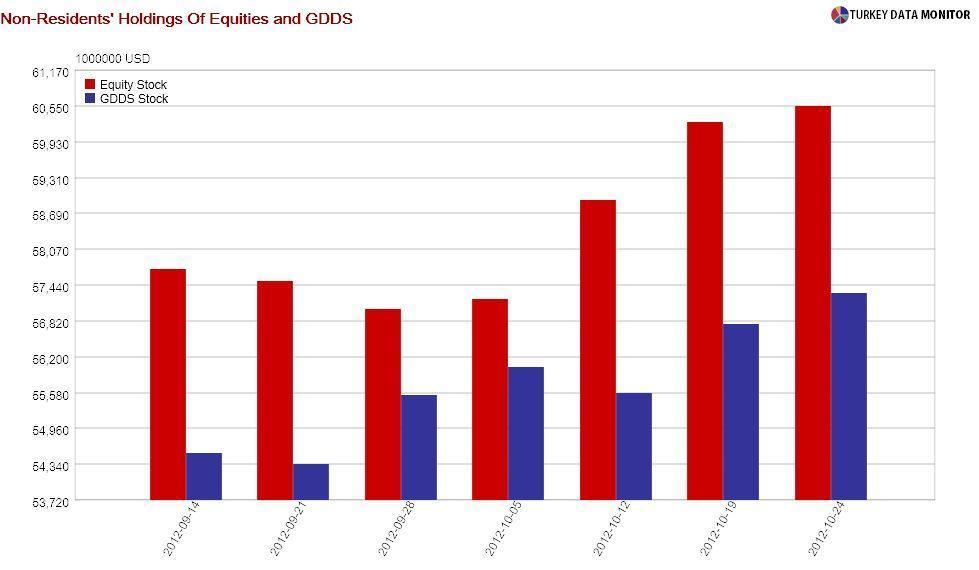

Turkey has been one of the main recipients of these flows. Of course, rumors of an upgrade to investment grade, which finally

materialized last week, played a role as well, especially for equities. But even a perennial pessimist like me has to accept that Turkey looks better than many of its peers.

Such flows are both a boon and bane for Turkey. On one hand, the Turkish growth model is reliant on external financing, so the economy will expand as long as

the money keeps rolling in. But on the other hand, this model exposes it to shifts in global financial conditions. If there were to be a sudden stop to capital flows, the country could end up with an exchange rate depreciation and recession.

In fact, at the credit rating agency’s packed Turkey Credit Outlook Conference in Istanbul on Thursday, Fitch analyst Ed Parker

underlined that such a scenario is likely. However, they decided to go with the upgrade anyway, as they believe there are “buffers against a full blown financial/sovereign crisis,” such as “strong government, bank and household balance sheets, economic flexibility and monetary and exchange rate flexibility.”

I am not so sure. For one thing, a casual look at this and

last year’s Medium-Term Programs reveals that the fiscal slippage this year will carry on to next year. Besides, the government does not have a good track record of sticking to its expenditure targets, so I am not taking next year’s budget deficit objective of 2.2 percent too seriously, especially as there are local and presidential elections in 2014 and general elections the following year.

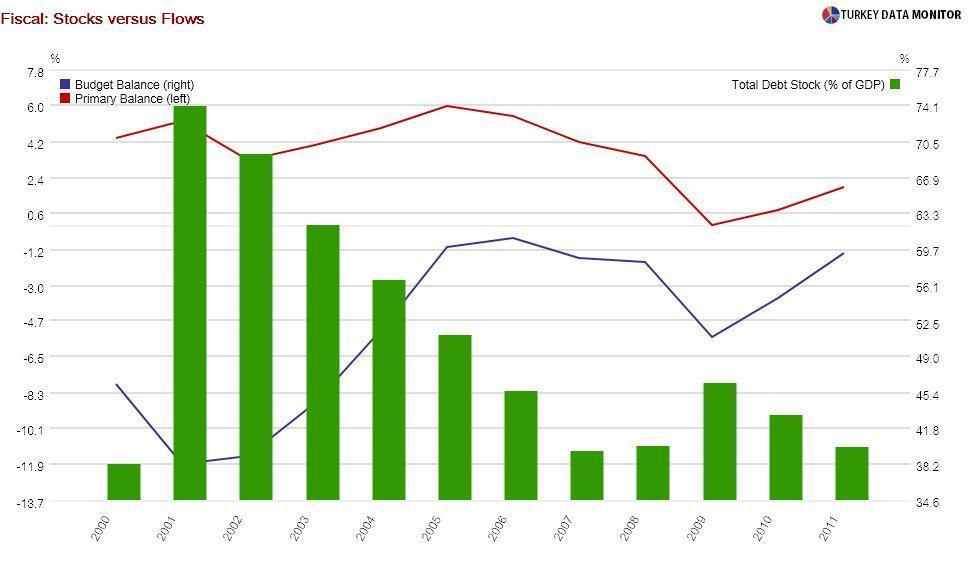

I feel that Fitch’s fiscal view gives a lot of importance to

“stocks,” such as the country’s low debt levels, and not enough weight to “

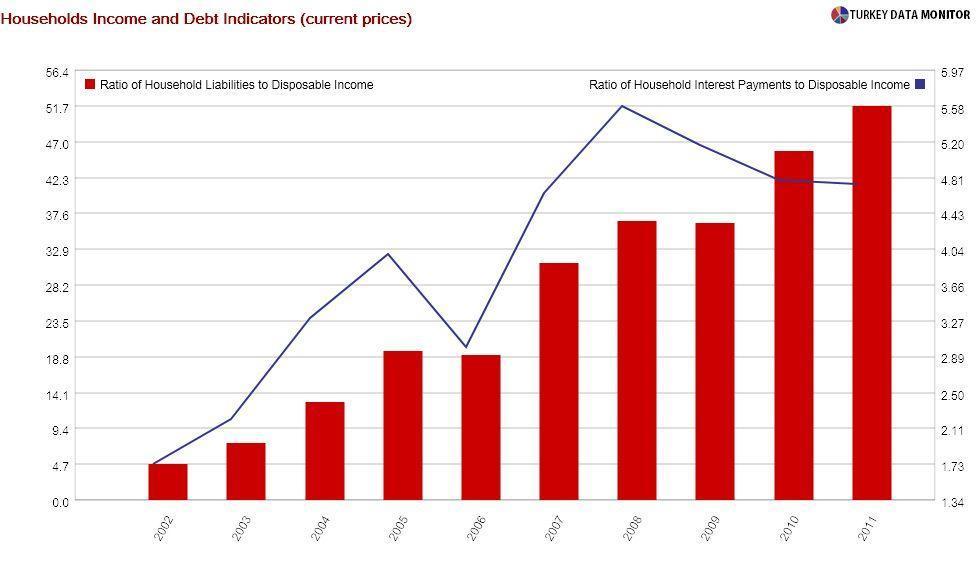

flows,” such as the worsening deficit. The same goes for household balances: While Turkish households are not indebted compared to their peers, their debt levels have nevertheless risen very fast during the last few years.

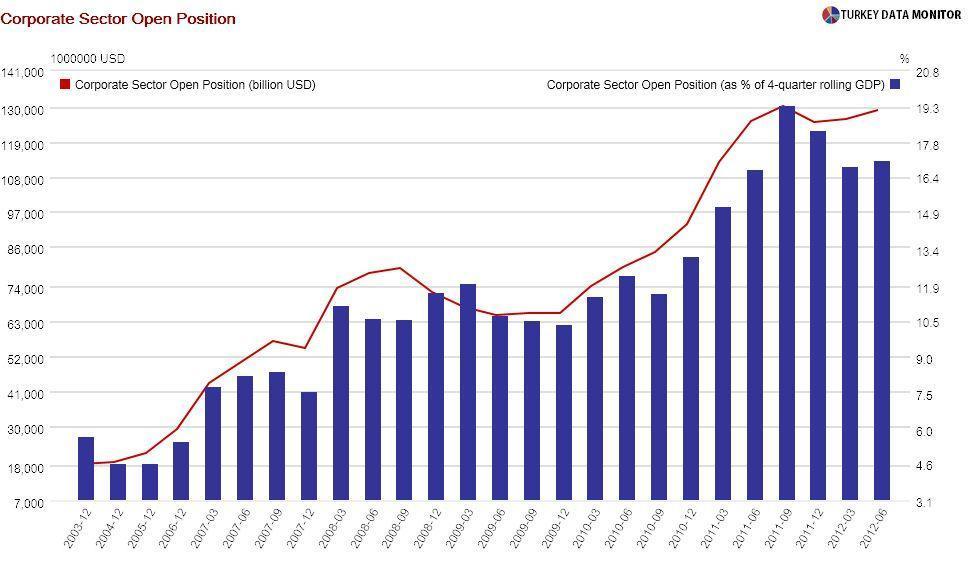

And I am not sure a flexible exchange rate

would help against the huge corporate open position. I asked Central Bank Deputy Governor Turalay Kenç, one of the speakers at the Fitch conference, if the Bank is not worried about this anymore. He mentioned that most of the open positions belonged to exporters, who have a natural hedge.

Nevertheless,

investors I spoke to in London last week mentioned a strong U.S. recovery and rising interest rates, which would put a stop to capital flows to Turkey, as the biggest risks facing the country.

It has been exactly two months since the Federal Reserve (Fed) announced its third round of quantitative easing, dubbed QE3.

It has been exactly two months since the Federal Reserve (Fed) announced its third round of quantitative easing, dubbed QE3.