QE será, será

I always dismissed arguments that the eurozone’s time as an economic power was up,

pointing out the strengths of the common currency area. But I finally realized that I have been wrong all along.

Before the European Central Bank’s

asset purchase announcement on Jan. 22, German Chancellor Angela Merkel

emphasized the ECB’s independence, while also underlining that it was important to avoid signals that could be “perceived as weakening the necessity for structural changes.” After the announcement, she

reiterated her view that stimulus should not be substitute for economic reform.

I was surprised that she did not

pressure the ECB before the decision. Neither

she (or

her inner circle) asked ECB President Mario Draghi to resign afterwards. I checked all the German papers, and not even the tabloids accused him of being part of an

interest rate lobby. The Europeans do not seem to understand that monetary policy is too sensitive a matter to be left to bureaucrats.

Luckily, Turkey is blessed with policymakers with foresight, who have been expecting the ECB’s quantitative easing (QE) for a long time and devising policy accordingly. What was their policy? Well, doing nothing… When an economist friend went through her regular Ankara meetings back in November, she was shocked to hear the same argument from almost everyone: The European stimulus would result in significant capital flows to Turkey and jumpstart the economy.

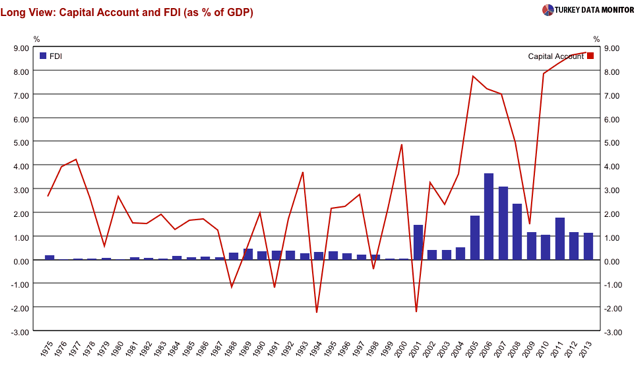

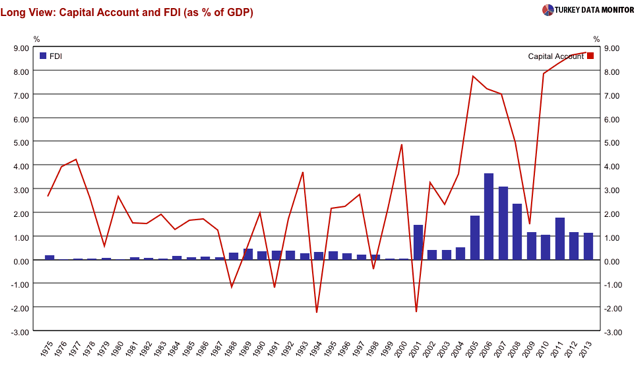

With low interest rates in advanced countries, it is likely that some of the extra liquidity from the ECB’s QE will find its way to emerging markets (EMs), especially those with relatively high yields such as Turkey. To have an idea of the potential size of such flows, it might be a good idea to look at the Fed’s three rounds of quantitative easing from November 2008 to October 2014.

After hitting 14 percent of their GDP before the global crisis, annual capital flows to EMs plunged to around 2 percent in 2009. They nevertheless surged with the advent of QE1 and continued rising until the end of QE2, all the way to 9 percent, before falling to 5 percent. They then started increasing again when QE3 kicked off, but they only reached to around 7 percent.

Even though it is likely to create short-term euphoria for EM assets, one cannot expect too much from an asset purchase program one-third the size of the Fed’s. Besides, almost all EMs have a weaker economy today than three years ago. Many are suffering from structural low growth, for which capital flows are no panacea. Commodity exporters are hurt by lower commodity prices, whereas those indebted in dollars will feel the sting of a stronger dollar. Speaking of the dollar, the rise in the Fed’s policy rate is likely to partly counteract the ECB’s QE.

As for Turkey, capital flows to the country surged after QE1, but consistent with the

high-beta status of Turkish assets, they never plunged, hovering in the 8-9 percent range 2010-2013. Therefore, the European QE could bring more capital to Turkey than other EMs. But with a high level of private sector foreign currency debt, most of it in dollars, Turkey is also poised to feel the pinch of the Fed’s tightening more than other EMs.

In any case, relying on hot money only delays the inevitable, even if the country does not end up with a crash associated with a sudden stop in capital flows: Mediocre growth and entrapment in the

middle-income trap.

I always dismissed arguments that the eurozone’s time as an economic power was up, pointing out the strengths of the common currency area. But I finally realized that I have been wrong all along.

I always dismissed arguments that the eurozone’s time as an economic power was up, pointing out the strengths of the common currency area. But I finally realized that I have been wrong all along.