Prioritizing Turkey’s reform agenda

For quite a while I have been pointing to the rising risks in the Turkish economy such as the

current account deficit and the accompanying external financing problem, unbalanced growth,

rising inflation and

confusing monetary policy.

But if you look at the big picture, the economic landscape is undoubtedly prettier than a decade ago. We owe this relative stability to the first Justice and Development Party (AKP) government’s adherence to the reform agenda that was implemented after the 2001 crisis.

Unfortunately, those macroeconomic reforms have not been followed by

microeconomic ones despite several government attempts to jumpstart the structural reform agenda, each time with a long list of policies covering many areas of the economy.

I am extremely

skeptical of such “laundry lists.” For one thing, without knowing the key reforms, we cannot be sure if we are getting the biggest bang for the buck. Besides, trying to tackle it all at once could lead to premature “reform fatigue,” which may explain the government’s failure at structural reforms so far.

But this would all be pointless pontification unless I explained how policymakers could go about choosing the most important reforms. Luckily for me, İzak Atiyas and Ozan Bakış have done exactly that in the aptly-titled report, “Constraints to Growth in Turkey: A Prioritization Study.”

The paper, which the media almost completely ignored and is only available in Turkish, applies the

well-known framework of Harvard Kennedy School professors Ricardo Hausmann, Dani Rodrik and Andrés Velasco, who share the misfortune of having had

your friendly neighborhood economist as teaching and research assistant, advisee or co-author.

Starting with “low return to economic activity” and “high cost of finance” as key impediments to growth and then branching out to specific areas, this approach uses a decision-tree process to identify the most critical constraints. Applying this methodology, Atiyas and Bakış conclude Turkish growth suffers more from low productivity than inadequate finance, with human capital as the main binding constraint.

This conclusion is supported by Turkish students’ low scores on

PISA exams, strong returns to higher education compared to peers and the low degree of sophistication of the country’s exports. It is also completely in line with Ankara think-tank TEPAV’s findings on the importance of (and lack of)

English language and computer skills among Turkish workers, which fellow Daily News columnist Güven Sak reported.

I hope the government is aware of the Atiyas-Bakış study, as it has important policy implications (other than investing in education). For one thing,

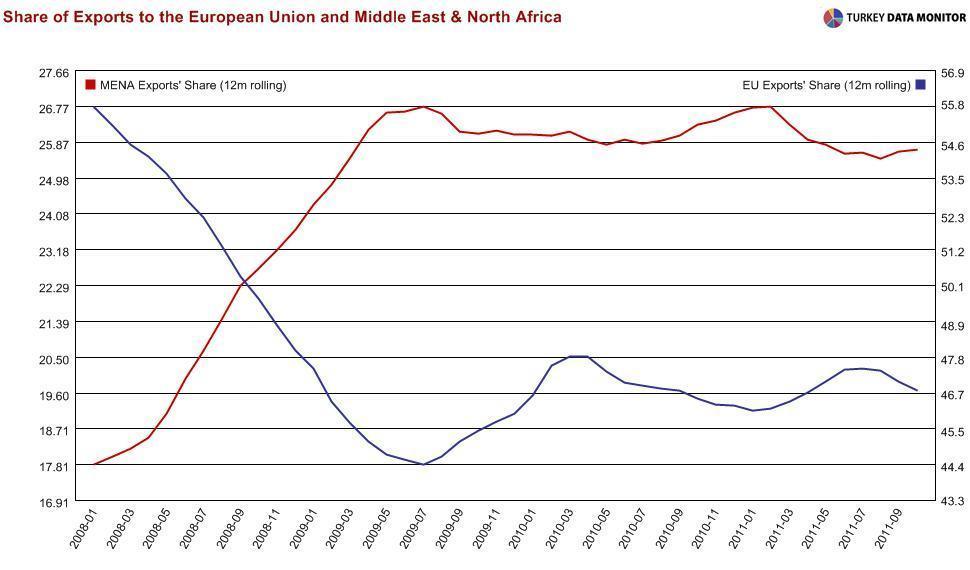

diverting exports from an ailing eurozone to markets that demand lower technology products may seem attractive now, but it may not be such a smart move, particularly in the long run. After all,

selling biscuits to Jordan (the country, not

Michael) will not increase the demand for more skilled labor.

It is also naïve to expect that a depreciated Turkish Lira will miraculously heal Turkey’s current account deficit and capital flows-financed growth model, unless the real binding constraints to growth are addressed.

For quite a while I have been pointing to the rising risks in the Turkish economy such as the current account deficit and the accompanying external financing problem, unbalanced growth, rising inflation and confusing monetary policy.

For quite a while I have been pointing to the rising risks in the Turkish economy such as the current account deficit and the accompanying external financing problem, unbalanced growth, rising inflation and confusing monetary policy.